INTRODUCTION

Monkeypox (Mpox), a zoonotic disease caused by Monkeypox virus (MPV) with symptoms similar to those seen in smallpox patients in the past in less severe form. MPV is a ds-DNA, enveloped virus belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus of the Poxviridae family. After cessation of smallpox vaccination post eradication in 1980, MPV has emerged as one of the important public health threats. Currently Mpox outbreak has been reported from various parts of the world although primarily it was seen in the Central and West Africa mainly in vicinity to tropical rainforests (1). Squirrels, rats, non-human primates etc. are thought to be animal reservoir (2). However, person to person transmission by respiratory droplets, fomites, and direct contact with lesions of an infected patient was observed in the current outbreak (3). Studies from recent outbreak showed high viral loads in saliva, urine, semen, feces, oropharyngeal swab and rectal swab etc. which strongly suggest possibility of sexual transmission (4) . The vertical transmission from infected mother to fetus has also been reported previously (5). Central African (Congo Basin) and the West African clade are the two genetic clades of MPV of which the Central African clade is more severe (case fatality ~10%) with high transmissibility. Cameroon is the only African country from where both MPV clades have been reported (1). In this review we have discussed about origin, epidemiology (pre re-emerging and current outbreak), preventive strategies and vaccines for Mpox.

ORIGIN

MPV was first isolated and identified in 1959 from a pox-like disease occurred in monkeys kept for research. Hence the name was given “monkeypox” although the exact source of the disease still remains unknown. The first human Mpox case was described in 1970 in Equatorial province of Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) when the virus was isolated from a 9-month-old male child suspected to have smallpox (3, 6).

PRE RE-EMERGING EPIDEMIOLOGY

Following the report of first confirmed Mpox case in 1970, other human Mpox cases have increasingly been reported from a total 11 countries of Central and West Africa (1). Between the periods of 1970-1979, World Health Organization (WHO) reported 54 confirmed human Mpox cases of which clinical and epidemiological characteristics were described by Breman et al in 47 cases (7, 8). Another report by Jezek et al. had described 57 cases from 1970-1980 (9). A total 338 confirmed Mpox cases with 9.76% case fatality were identified by WHO between 1981 and 1986 through active surveillance. The increase number of cases probably attributed to active surveillance as there was no much difference in the number of cases reported from other areas not under WHO surveillance (9, 10). Person to person transmission was observed very rarely from secondary cases (11). There was no enormous change in the secondary attack rate in initial outbreaks of Mpox for household contacts which suggests no change in the transmissibility pattern of the virus (12). According to WHO report, animals were responsible in 72% cases for primary infection and person to person transmission was observed in 28% (13). Predominantly (86%) male children less than 10 years of age were affected and majority of the primary cases were unvaccinated against smallpox. During 1981-1986 WHO surveillance a total 774 unvaccinated contacts of reported cases were tested and 136 (18%) were found to be positive for MPV (9). After discontinuation of the WHO intensified surveillance, outbreaks were reported in small numbers between1987 and 1992 (13, 14, 15). There was no reported outbreak since 1993 to 1995. During 1996-1997, outbreak of human Mpox was reported from DRC with a total 511 suspected cases (16). Although the case fatality was around 1-5% but secondary cases (~78%) was much higher than previously reported (13). From February - August 2001 a total 31 patients were reported from separate outbreaks suspected to have Mpox in DRC. Samples from 14 suspects were tested and seven were positive for MPV. Out of total five deaths reported, four were confirmed Mpox cases (17). According to the DRC Ministry of Health National Disease Surveillance Program report, a total 2734 suspected human Mpox cases were reported during 2001-2004 from 11 DRC provinces. Only a total 171 clinical samples from 136 patients were collected and tested due to effect of civil war on the surveillance program. A total 37.5% were positive for MPV, 44.8% for Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) and 0.7% for both. According to the available data, mean age of MPV infected cases were around ten years, whereas the mean age of VZV infected cases were 20.6 with no difference in sex (18). During 2005-2007, a total 760 laboratory confirmed Mpox cases were identified by the DRC surveillance program. Most of the cases were around 12 years of age and almost 92.1% of the patients were born after 1980 (mass small pox vaccine campaign) with 62.1% male cases. The average annual Mpox incidence was 20 fold increased according to this DRC surveillance report as compared to the data of previous surveillance study done in 1980s (19). In 2010, outbreaks reported from Likouala region of Congo Republic with 10 cases (2 confirmed, 8 suspected) and two confirmed cases from Central African region (7, 20). The outbreak from Central African region was associated with hunting and eating of a wild rodent called Bemba. In 2013, there were 104 suspected cases of Mpox reported from the Bokungu health zone of DRC. A total 50 cases were laboratory confirmed out of the total 60 tested which was very high than previously reported from that zone. High transmissibility was observed as the household attack rate was almost 50% (21). Sierra Leone in 2014 experienced a comeback of Mpox after 40 years, with a single laboratory-confirmed case (22). Another outbreak of Mpox was reported from Likouala province (Congo Republic) and was notified to the WHO on February first, 2017. In that outbreak a total 70 Mpox cases were reported with four fatalities. The majority of the cases (around 60%) were children under the age of 15, with no significant difference in sex. 18 villages were affected from the five districts namely Betou, Dongou, Enyelle, Impfondo and Owando from that province. A total 43 samples were tested at the Institut National de Recherche Biomédicale (INRB), Kinshasa, out of which total seven came positive for MPV using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (23). Since 2017, Nigeria has also reported more than 500 suspected cases out of which a total 200 were confirmed. The case fatality ratio is around 3%, and new cases are still being reported (1). An outbreak of total 269 Mpox suspected cases were reported from 25 states and one territory with a total 115 confirmed cases from 16 states and one territory during September 2017 to September 2018. Seven deaths were recorded, with four of them being patients with prior immunocompromised conditions. Among the confirmed cases, two were healthcare workers. Most of the cases were from 21–40 years age group with male predominance (79%) (24).

OUTBREAKS IN OUTSIDE AFRICA

In 2003, the United States (US) have experienced Mpox outbreak which was first Mpox outbreak outside of Africa. A total 47 confirmed and probable Mpox cases were reported from six states—Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio and Wisconsin. All the cases had contact history with pet prairie dogs. These pets probably got infected from imported African rodent (African giant pouched rats, dormice, and rope squirrels). After importation into the US, some of the infected animals were housed near prairie dogs at the facilities of an Illinois animal vendor. These prairie dogs were sold as pets before they developed signs of infection (25). Apart from that, Mpox cases have been recorded in Nigerian travellers in many countries, including Israel (September 2018), the United Kingdom (September 2018, December 2019, May 2021, and May 2022), Singapore (May 2019), and the United States (July and November 2021). Furthermore, multiple cases were reported from many non-endemic countries in May 2022 (1).

CURRENT OUTBREAK

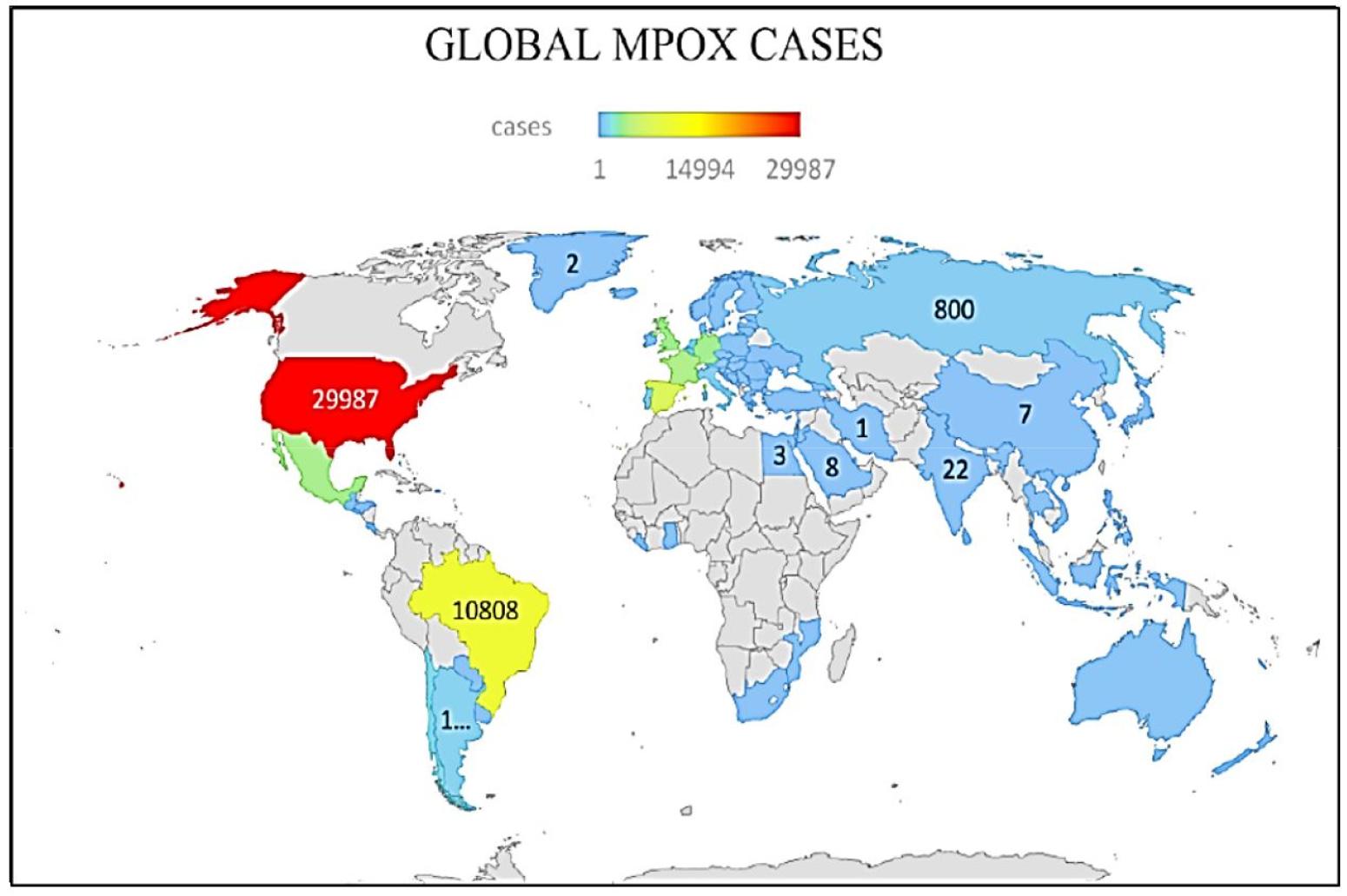

Since January 2022, human Mpox cases have been reported from 110 member states of all six WHO regions. Till 18th February 2023, a total of 86,019 laboratory confirmed Mpox cases, 1389 probable cases with 96 fatalities have been recorded and informed to WHO. From May 2022, a large number of Mpox cases have been notified from countries with no prior history of Mpox. In this outbreak no immediate or direct epidemiological link between Mpox reported countries and central or West Africa have been observed. The incidence rate of Mpox globally has been reduced. Recent cases reported mainly from Americas (79.8%) and from African region (11%). The top 10 most affected countries globally are: USA (total cases 29987), Brazil (total cases 10,808), Spain (total cases 7538), France (total cases 4,128), Colombia (total cases 4080), The United Kingdom (total cases 3735), Germany (total cases 3692), Peru (total cases 3,698), Mexico (total cases 3,696), and Canada (total case 1,460). These countries were responsible for 84.9% of the total Mpox cases reported worldwide in the current outbreak (25). World map showing distribution of reported cases was shown in Fig. 1.

SITUATION IN AFRICA

Till 18th February 2023 a total 1379 cases of confirmed Mpox with 16 fatalities were reported from the African region which constitute global 2% of cases and 17% of deaths. The details of 401 (29%) cases were submitted to WHO of which 245 (61.1%) cases were males with median age of 23 (26).

SITUATION IN EUROPE

Till 14th February 2023 a total 25839 Mpox cases have been identified from the 45 countries of European region. European surveillance system have reported to the WHO regional office for Europe and European centre for Disease Prevention & Control (ECDC) case related data of 25741 cases from the 41 countries and areas of the region. Out of those a total 25558 cases were laboratory confirmed. 489 cases of total tested were confirmed to belong to Clade II (West African) (27). A total 39% cases belongs to 31 - 40 years of age group with male predominance (98%). Higher incidence of Mpox cases were seen among men who have sex with men (MSM). A total five cases were reported to be died from the region (27).

OUTBREAK IN INDIA

India became the first country from the WHO South East Asia region to experience Mpox case in a 35 year old traveller who came from the Middle East on 14th of July 2022. As of 18th February 2023, a total 22 confirmed cases with one death were reported from India (28, 29).

PREVENTIVE STRATEGIES

The current available data suggests that MSM, bisexual, and gay constitutes the most of the cases in the recent outbreak of Mpox. However, close contacts with confirmed Mpox case are at risk irrespective of gender or sexual orientation (30). To prevent this infection, direct contact (skin-skin, sexual) with suspected Mpox cases and contact with used materials by suspected cases and animals such as primates, rodents etc. should be avoided (31). Hand hygiene and vaccination also plays an important role in prevention. Protection will be highest after two weeks of second dose of vaccine (32).

MPOX AND HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS (HIV)

The recent available data statistics suggests that around 40% of people diagnosed with Mpox are also co-infected with HIV in the United States. HIV related symptoms may not be present in confirmed Mpox cases. Mortality and morbidity is more among patient with severe immunocompromised conditions (advanced HIV) (33, 34, 35). As per limited research statistics, HIV infected patient with CD4 count of < 350 cells/ mL or high viral load are more likely to be hospitalized due to Mpox infection as compared to patient without HIV infection. Drugs used for Mpox treatment may have minimal interactions with HIV drugs (34).

MPOX AND PETS

Mpox cases can spread the virus to pet animals through close contact and animals infected with Mpox virus can also spread it to human and other animals. Pets that have been in close contact with Mpox cases should undergo 21-days of isolation from humans and other animals (36).

VACCINES

To end Mpox globally, the primary objective is to stop its spread to various countries by interrupting the transmission and to protect high risk and vulnerable groups from severe Mpox disease.

PRE-EXPOSURE VACCINATION

Pre-exposure vaccination is ideal for at risk groups as seen in the current outbreak such as MSM, bisexual, gay, people having more than one sexual partner, prostitutes, laboratory and health care worker and outbreak management team members etc. However pre-exposure vaccination is not recommended in children, pregnant women and immunocompromised person (37).

POST-EXPOSURE VACCINATION

It is advisable for contacts of confirmed/susceptible cases to receive post-exposure vaccination, preferably within four days of initial exposure and till 14 days in case no development of symptoms. Priority should be given to women in pregnancy, Children and individuals with immunocompromised states, as they are more prone to severe Mpox disease if infected (37).

Recommendation of vaccine against Mpox as per the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, the United States (38)

ㆍIf there is a known or suspected exposure to an Mpox case.

ㆍSexual intercourse with a case of Mpox in last 14 days.

ㆍAn individual, who identifies as MSM, bisexual, gay, transgender, nonbinary, or gender-diverse, has engaged in sexual activity with multiple partners, had sex at a commercial sex place, participated in sexual activity at an event, or in an area in last 14 days, where Mpox transmission is occurring.

ㆍMSM, bisexual, gay, transgenders, non-binary, or gender – diverse individuals who had diagnosed with sexually transmitted infections such as HIV, Syphilis, Gonorrhoea, Chlamydia etc. in the past six months.

ㆍAny person who engaged in sexual activity at commercial sex place, occasion, or in an area where Mpox transmission is occurring in the last six months

ㆍLaboratory personnel who work with Orthopoxviruses.

Vaccines available against Mpox are shown in the Table 1. (39, 40, 41, 42).

Table 1.

| Name of Vaccine | Type of Vaccine | Age | Route of Administration | Dosage | Constituents | Remark | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JYNNEOS vaccine | live virus vaccine | ≥18 years | subcutaneous |

2, 4 weeks apart 0.5 ml | Modified Vaccinia Ankara-Bavarian Nordic (MVA-BN) | Can be administered to immune compromised patient | FDA, JYNNEOS Vaccine (39) |

| ≤18 years | subcutaneous |

2, 4 weeks apart 0.5 ml | |||||

| ≥18 years | Intra dermal |

2, 4 weeks apart 0.1 ml | Used in current outbreak | ||||

| ACAM2000 vaccine | Live virus vaccine | ≥1 years | Percutaneous, delivered using a bifurcated needle | Single dose of 0.0025 mL droplet reconstituted vaccine | Live vaccinia virus, trace amount of neomycin and | Not recommended in immunocompromised patients, pregnant women | FDA ACAM2000 vaccine (40) |

| APSV: Aventis Pasteur smallpox vaccine | Live replicating vaccinia virus | ≥1 years | Percutaneous, delivered using a bifurcated needle, multiple puncture | Single dose | Investigational vaccine | CDC vaccines (41) | |

| LC16m8 | Live replicating attenuated vaccine | - | scarification | Single dose | Live, replicating attenuated vaccine (derived from Lister (Elstree) strain) | Active immunization against smallpox, used in Japan (Clinical trial) | Yano R et al (42) |

CONCLUSION

As Mpox is reported from beyond its endemic zone in the current outbreak and becoming a global health concern, appropriate preventive measures should be taken to prevent its transmission. Human-to-human transmission can be prevented by avoiding direct/sexual contact, keeping social distancing, hand hygiene, droplet precaution etc. Vaccination will also play an important role in its prevention. Contact tracing will play vital role as the source of this outbreak yet to be established. Studies are required to check for any new development in the virus properties also. Small pox vaccination programs may be restarted in many countries to prevent future Mpox outbreaks.