INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most widespread bacterial pathogens, representing a never-ending threat to public health. This bacterium is well equipped with many virulence factors that enable it to cause a range of diseases, from mild skin infections, such as folliculitis, furuncles, carbuncles, and impetigo, to more serious, life-threatening conditions, such as pneumonia, bloodstream infection, meningitis, and endocarditis (1, 2). In addition to its vast array of virulence factors, S. aureus has a remarkable ability to acquire resistance to many antibiotics, which culminated in the emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in 1961 (3). MRSA is a specific biovar of S. aureus that has virulent zoonotic characteristics and carries the mecA gene, coding for a low-affinity penicillin-binding protein (PBPa2), which enables these strains to exhibit resistance to methicillin and cefoxitin (4). Initially, MRSA infections were restricted to hospitals and patients with identified risk factors, including those with a history of healthcare setting exposure, immunocompromised individuals, and those who inject drugs repeatedly (5). However, the emergence of the new S. aureus strains did not stop at this end. MRSA infections outside of hospitals began to be recorded in children in the early 1990s without predisposing factors (6). These strains were called community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA), characterized by high pathogenicity and ability to spread to healthy individuals. The distinguishing features of CA-MRSA are resistance to β-lactam antibiotics only and harbouring the Panton-Valentine Leucocidin gene (pvl), which encodes leucocidin toxin responsible for tissue invasion (7, 8). Although hospitals and healthcare settings are considered the source of healthcare MRSA, little is known about the sources of CA-MRSA. Epidemiologically, humans are implicated as the primary source of CA-MRSA, with approximately 30% of the general population estimated to carry S. aureus in the nasal cavity (9). However, MRSA has also been found in food production animals, which is termed livestock-associated MRSA (LA-MRSA), and also in companion animals (cats and dogs) (10). Previous studies have shed light on the role of companion animals, particularly cats and dogs, in spreading S. aureus and found that these pets may act as reservoirs of MRSA, contributing to some extent to the spreading of CA-MRSA (11, 12, 13). Despite the substantial increase in reports of MRSA infections in humans caused by contact with companion animals in recent years (13, 14, 15), the prevalence of S. aureus and MRSA in dogs and cats has received little attention, especially in Middle Eastern countries, particularly Iraq. Investigating the prevalence of pathogenic S. aureus in companion animals is important for the following reasons: firstly, the carrier animals may infect themselves with severe forms of infections; secondly, the carrier animals may act as sources of infection for other animals or their owners; thirdly, Accurate control policies can be developed to control CA-MRSA infections in the community through appropriate household infection control guidelines. Thus, the primary aim of this study was to investigate the S. aureus nasal carriage in companion animals (cats and dogs) in animal shops in Al-Nasiriyah city, and the secondary aim was to explore the risk factors for the carriage of pathogenic S. aureus, providing essential information to guide policymakers and further studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design, Population, and Area

This cross-sectional study of S. aureus nasal carriage in pets included 287 pets (164 dogs and 123 cats) from all pet shops (n = 14) in Al-Nasiriyah, Thi-Qar province, southern Iraq. To explore the nasal carriage of pathogenic S. aureus and examine the associated risk factors, available demographic information was collected, including age (estimated by dentation and categorised into three groups: < 1-year-old, 1–2 years old, and > three years old), sex and breed.

Sample Collection

The pet shops were visited weekly for seven months (28 visits extended from 1 June 2023 to the end of January 2024) to collect nasal swabs from the 287 animals (one swab per animal). Veterinarians collected the swabs professionally from apparently healthy animals using a sterile cotton swab soaked in normal saline. The swab was inserted into both nostrils with rotation to a depth of 0.5–1 cm; if the nasal orifices were too small, the swab tips were rubbed only at the entrance of the nasal orifices. The swabs were placed in a peptone water broth tube supplemented with 20% sodium chloride. Within two hours, they were transported in an ice box to the microbiology laboratory of Al-Nasiriyah Technical Institute, Southern Technical University, for analysis.

Ethical Approval

The study plan was approved by the Scientific Committee of the Public Health Department of Al-Nasiriyah Technical Institute. Since the study did not involve invasive procedures in sample collection and samples were collected by a veterinarian, it was also approved by the Animals Experiments Committee of Al-Nasiriyah Technical Institute.

Isolation and Identification of S. aureus

A 100-µl transport medium (peptone water) was streaked onto mannitol salt agar (MSA) and incubated for 24–48 h at 37°C. Suspected colonies exhibiting the morphological characteristics of S. aureus, including round, smooth colonies with a turning medium yellow color, were sub-cultured on MSA to obtain pure colonies. The pure colonies were subjected to traditional biochemical tests, including Gram staining, catalase and coagulase. Additional tests, including acetoin production and resistance to polymyxin, were used to further discriminate between S. aureus and S. pseudintermedius, as only S. aureus showed positive reactions to these tests (16). Finally, colonies were identified as S. aureus by VITEK®2 COMPACT (Biomerieux®, France).

DNA Extraction

Bacterial DNA was extracted using a commercially available kit (GeneaidTM DNA isolation, Thailand). The amount and purity of the extracted DNA were estimated by NanoDrop (NAS900, Taiwan).

Molecular Identification of S. aureus and Detection of mecA, pvl and tsst-1 Genes

The conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique was conducted using four pairs of primers: the identification primer (species-specific 16S rRNA) and primers for the detection of virulence genes (mecA, pvl, and tsst-1). The sequences, annealing temperatures, and product sizes of these primers are presented in Table 1. The reaction mixture consisted of 5 µl of extracted DNA, 1 µl of each forward and reverse primer (10 pmol), and 5 µl of ready-to-use master mix (AccuPower, Bioneer®, Korea). The final volume (0.2 ml) was completed with deionized water. The amplification conditions for these primers have been described in previous studies (7, 17, 18, 19).

Table 1.

The primer sequences, annealing temperatures and product sizes of the primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequences 5’-3’ | Annealing temperature (°C) | Product size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA |

AACCTACCTATAAGACTGGG CATTTCACCGCTACACATGG | 54 | 570 | (17) |

| mecA |

GTAGAAATGACTGAACGTCCGATAA CCA ATT CCACATTGTTTCGGTCTAA | 50 | 310 | (18) |

| pvl |

ATCATTAGGTAAAATGTCTGGACATGATCCA GCATCAAGTGTATTGGATAGCAAAAGC | 56 | 430 | (7) |

| tsst-1 |

TGGTATAGTAGTGGGTCTG3 GGTAGTTCTATTGGAGTAGG3 | 50 | 271 | (19) |

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by SPSS version 26. Categorical variables (age, sex and breed) were expressed as percentages (%). Descriptive statistics were used to determine the prevalence of S. aureus in both populations (cats and dogs). Fisher’s exact test was used to find the significant differences in S. aureus prevalence between cats and dogs. Risk factors were assessed by univariate analysis using the Chi-square test. Values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Population

Table 2 illustrates a description of the study population. This study included 287 pet animals (42.8% cats and 57.2% dogs). About 44.7% of the cat population were young (1–3 years old), with kittens (< 1 year old) constituting 33.4%, while adults (> three years old) made up 21.9%. Males (55.3%) outnumbered females (44.7%). Most of the cats in the study population were of the Shirazi breed (64.3%). For dogs, most (45.2%) were adults, with the young group (1–3 years old) constituting 40.8% and puppies constituting the smallest group at 14% only. About 60.4% of the dogs were male, and 58.5% belonged to the Terrier breed, with only four (2.4%) being German Shepherds.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the study population

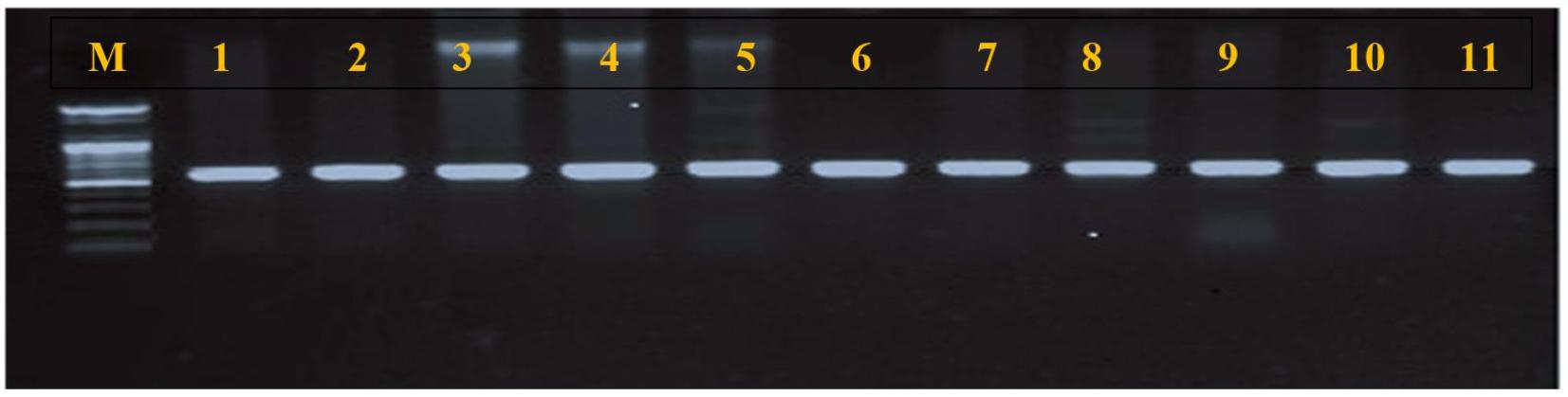

Isolation and Molecular Identification of S. aureus

Table 3 represents the detection rate of S. aureus from the nostrils of the study population. Out of 287 nasal swabs, only 38 (13.24%) yielded a characteristic morphology of S. aureus colonies on MSA. The PCR amplification of 16S rRNA using a species-specific primer revealed that all isolates (100%) were S. aureus based on the product size (Fig. 1) and sequence analysis of the amplified products. The detection rate of S. aureus in cats was 17/123 (13.8%), higher than in dogs 21/164 (9.14%). However, this difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Molecular Detection of Virulence Factors

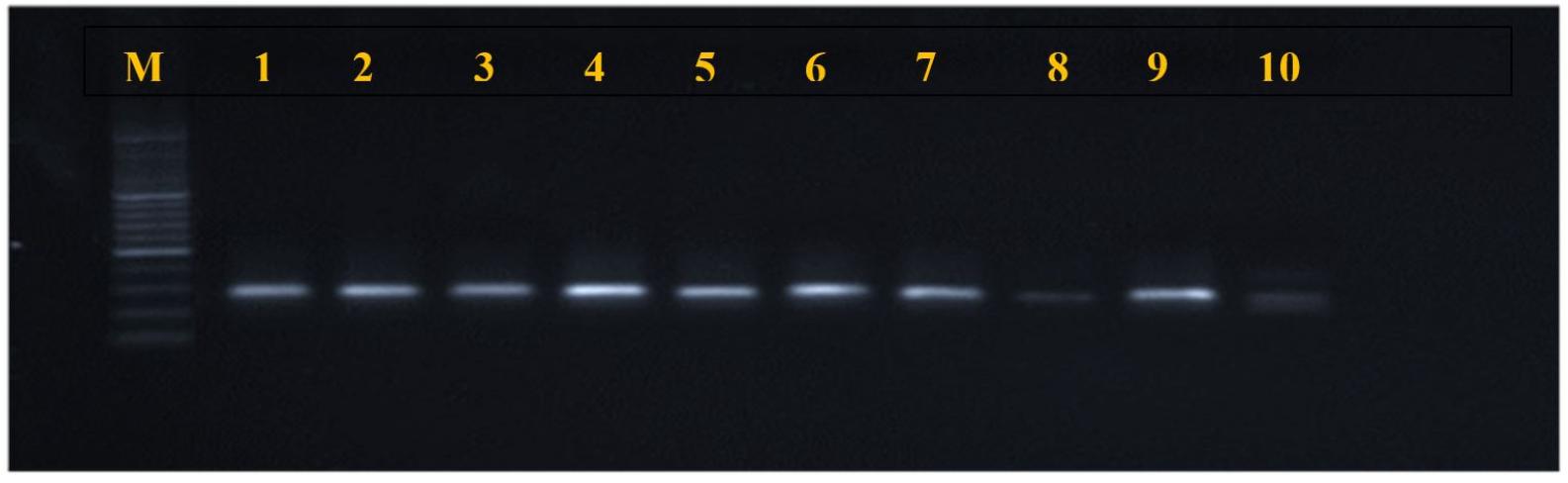

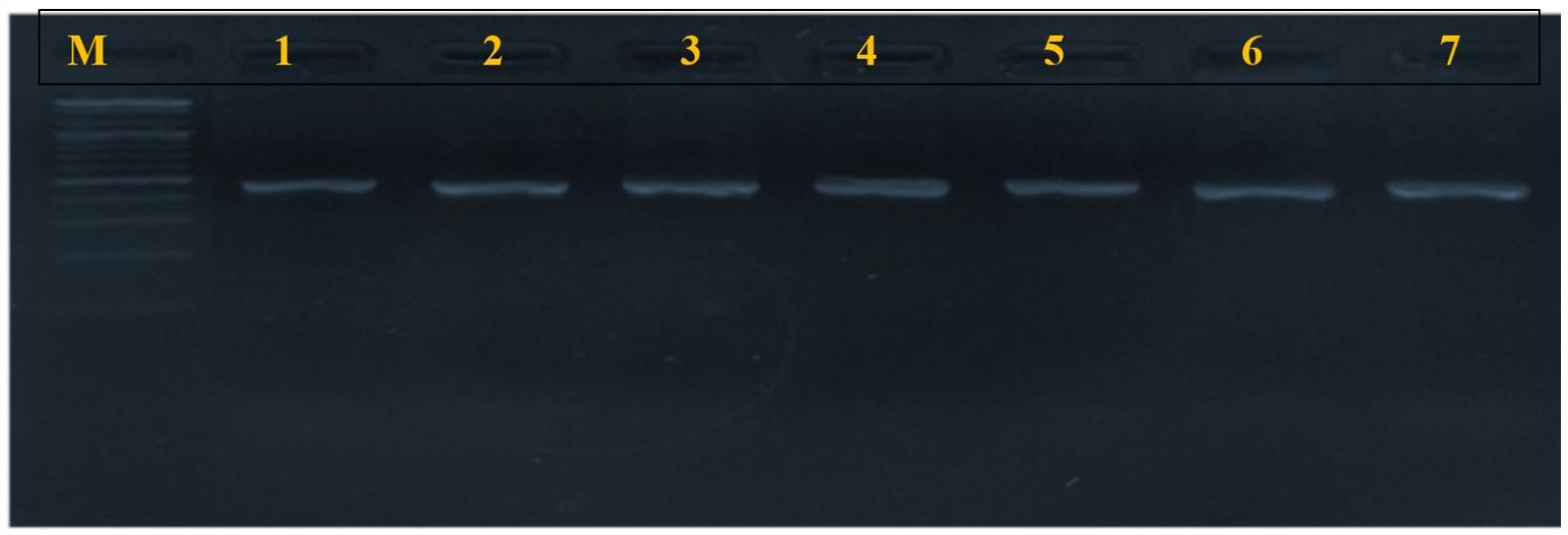

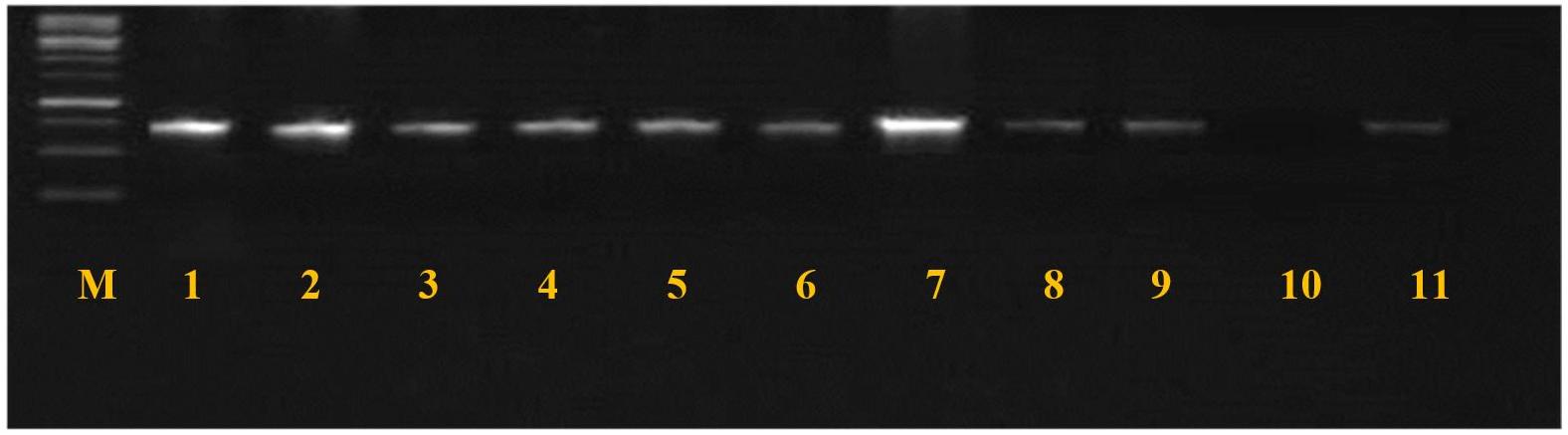

The results of the molecular screening for virulence genes are illustrated in Table 4. The most prevalent virulence gene was mecA, detected in 19/38 (50%) of S. aureus isolates. The overall prevalence of MRSA in the entire pet population was 6.62% (n=19 of 278) and 5.69% (n=7 of 123) in cats, and 7.31% (n=12 of 164) in dogs. The pvl gene was found in 18/38 (47.36%). The tsst-1 gene was detected in only nine isolates (23.68%). Figs. 2, 3, and 4 present the PCR amplification of virulence genes. The prevalence of mecA and tsst-1 genes was higher in the dog isolates (57.14% and 50%, respectively) than in the cat isolates (41.17 and 17.6%, respectively); however, these differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Conversely, the pvl gene was detected in a higher percentage of the cat isolates (58.8%) than in the dog isolates (38%), but statistically, no significant difference was found (P > 0.05).

Table 4.

Detection percentage of virulence factors in S. aureus isolates from cats and dogs

Fig. 2

mecA gene amplification products (310 bp), electrophorized in agarose gel (2%), under current 400 mA, and voltage (5 V) for 45 minutes. M: molecular marker (2000 bp); lanes 1-10 positive amplification.

Fig. 3

pvl gene amplification products (433 bp), electrophorized in agarose gel (2%), under current 400 mA, and voltage (5 V) for 45 minutes. M: molecular marker (2000 bp); lanes 1-7 positive amplification.

Fig. 4

tsst-1 gene amplification products (271 bp), electrophorized in agarose gel (2%), under current 400 mA and voltage (5 V) for 45 minutes. M: molecular marker (2000 bp); lanes 1-9 and 11 positive amplification; lane 10 negative amplification.

All S. aureus strains were assigned to five genotypes (I-V) based on different combinations of screened virulence genes (Table 5). About half of S. aureus strains 18/38 (47.36%) belonged to the non-pathogenic genotype (V), in which all screened virulence genes were negative (mecA-, pvl-, tsst-1-). This was followed by genotype I, the most virulent genotype in which all investigated virulence genes were positive (mecA+, pvl+, tsst-1+)) at 23.68% and genotype II (mecA+, pvl+, tsst-1-) at 21%. The mecA and pvl were the most frequently combined genes 17/38 (44.73%). Genotypes III and IV were detected at lower percentages (5.26% and 2.63%, respectively) and were found only in the dog isolates. No statistical significance was found regarding the distribution of genotypes I, II and V between cats and dogs.

Table 5.

Typing of S. aureus strains based on different combinations of virulence genes

Risk Factors of S. aureus Nasal Carriage in Pets

Table 6 presents the univariate analysis of the available risk factors of S. aureus nasal carriage in pets of this study. In both cats and dogs, only age variables, particularly the younger age groups (> 1 year old, puppies and kittens), are significantly associated with S. aureus nasal carriage (P<0.05). However, sex and breed variables have no significant associations with S. aureus nasal carriage (P> 0.05).

Table 6.

Univariate analysis of risk factors for the S. aureus nasal carriage in the study population

DISCUSSION

Due to the recent security, stability and economic improvement in Iraq, many families in Al-Nasiriyah have turned to obtaining pets for their homes. In light of the significant role of companion animals in the transmission of several diseases (20), this study was designed to investigate the S. aureus nasal carriage and virulence profile in companion animals as well as to explore the carriage-associated risk factors. The nasal carriage of S. aureus in companion animals was 13.2% (13.8% in cats and 9.4% in dogs). Unfortunately, comparing the nasal carriage rate in this study with other local-level studies is challenging, as this study was the first investigation of S. aureus nasal carriage in companion animals in Iraq. However, the nasal carriage found in this study was consistent with previous global studies, which state that the S. aureus nasal carriage in healthy cats ranges from 2.48–19.7% (12, 21, 22, 23, 24), and in dogs ranges from 5.8–12% (21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27). In contrast to studies investigating S. aureus nasal carriage in humans, which mostly report carriage rates ranging from 20–30% (28, 29), discrepancies exist among studies examining the nasal carriage rates in companion animals. A higher nasal carriage rate was recorded by Decline et al. (11) who reported 48%. Miszczak et al. (30) reported nasal carriage rates of 36.81% in healthy cats and 36.46% in healthy dogs, and an Algerian study reported a nasal carriage rate of 25% (22.6% in cats and 27.6% in dogs) (31). There appears to be no limited range for the nasal carriage of S. aureus in healthy cats and dogs. This could be attributed to variations in geographical distribution, sampling procedures, and sampling sites or diagnostic protocols. Regarding the carriage rate based on pet species, this study found no significant differences (P>0.05) between cats and dogs; a similar finding was reported by previous studies (24, 32). This can partly be explained by the relatively similar contact rate of companion animals to humans, as many studies stated that contact with humans is the main risk factor of S. aureus colonization in companion animals (33, 34). Regarding MRSA carriage, an interesting finding of this study showed that 50% of S. aureus strains were MRSA based on the detection of mecA gene (41.17% in cats and 57% in dogs), which was in agreement with findings obtained by Decline et al., in Indonesia (11) and higher than the results of Djebbar et al., (31) who detect mecA gene at percentage 15.4%. The prevalence of MRSA in this study was 6.62% (7.3% in cats and 5.69% in dogs), which was in agreement with Djebbar et al., who reported 6.6% (31) and in line with Mairi et al. (35) who reported 4.3%. On the other hand, the prevalence of MRSA in cats in this study (7.3%) was lower than the 10.2% reported in Poland (36) and higher than the 2.6% documented in Germany (24). The prevalence of MRSA in dogs in this study was in agreement with González-Domínguez et al. (37); however, previous studies recorded lower prevalence ranging from 0-3.5% in dogs (21, 32, 38). The detection of MRSA in healthy companion animals supports the hypothesis that these animals represent a reservoir of MRSA that may threaten public health – a conclusion reached by several previous studies as well (15, 39, 40).

Panton-Valentine leucocidin (pvl) is a bi-component, non-hemolytic toxin that causes a cytotoxic effect on leukocytes and is associated with supportive skin infections, mainly carried by CA-MRSA (7). This study found that 47.36% of S. aureus strains carry the pvl gene, consistent with a high incidence of pvl recorded in previous Iraqi studies (41, 42). In this study, the detection rate of pvl in cats was higher than in dogs; a similar finding was observed in the previous study (31). Also, in this regard, the findings of this study agreed with Mairi et al. (35). Additionally, the most frequently accompanied virulence genes in this study were mecA and pvl (47.36%), indicating that the strains were CA-MRSA as the pvl gene is a molecular marker of CA-MRSA (43). This study’s results revealed that nine (23.68%) S. aureus strains carry the tsst-1 gene, which encodes the protein for toxic shock syndrome toxin. Only two previous studies investigated the occurrence of tsst-1 in companion animals; the first one was in the U.K. investigating healthy dogs and found only one MRSA-positive strain also harboring tsst-1 gene (44), and the second study was higher than the current study’s result as he found 40% of S. aureus isolated from dog’s ear carrying tsst-1 gene (45). It has been documented that the detection rate of the tsst-1 gene in S. aureus isolated from clinical samples in Iraq was 46.7% and 43% (46, 47). Thus, it is logical that the S. aureus strains in this study were originally transmitted from previous pet owners. The combination of pvl and mecA genes in this study was 8/38 (21%), which was in agreement with Shrestha et al. (48). However, our results disagreed with the previous Iraqi study (49), which reported that 100% of MRSA were PVL positive. Similarly, the prevalence of the PVL gene was 79% among MRSA (7). This disagreement could be attributed to the source of isolation, as these studies have isolated MRSA from human clinical samples. It has been documented that PVL-positive MRSA causes severe skin infections and life-threatening infections (7). Additionally, previous studies showed that the PVL gene was detected in MRSA more than in MSSA (48). In this study, 23.68% of S. aureus were positive for mecA, PVL and tsst-1 genes, which was lower than those reported in Egypt (50). MRSA strains harbouring PVL and tsst-1 genes have been reported to cause severe infections with high mortality and morbidity (50).

Risk factor analysis in this study found that only age (> 1 year old) was significantly associated with nasal carriage in both cats and dogs; a similar finding was obtained by Djebbar et al. (31). This could be explained by the close contact that young companion animals have with their owners, a hypothesis proposed by previous studies (25, 51). Other studies examined the age, sex, breed, and previous medical history as risk factors for S. aureus colonization. Still, none have found any significant association with the nasal carriage of S. aureus in companion animals (21, 52). Failure to find significant risk factors for S. aureus colonization in cats and dogs could be attributed to the S. aureus not being a common colonizer of cats and dogs in nature.

The present study’s strengths include the following: 1- It is the first study to investigate S. aureus nasal carriage in pets in Iraq; 2- S. aureus was precisely identified and distinguished from S. pseudintermedius using species-specific primers and sequence analysis of the products; 3- The study included a relatively large population of cats and dogs; 4- Most previous studies worked only on household pets, while this study investigated pets from companion animal shops as well, meaning the nasal carriage of this study population is a reflection of many previous owners and households. However, there are some limitations. Firstly, this study did not explore many risk factors associated with MRSA carriage in pets, such as information about previous owners (occupation, S. aureus nasal carriage, number of pets in the household, number of family members, etc.). Thus, the genetic relatedness of pet isolates with those of their owners was not determined. Similarly, the pet’s medical history (previous diseases, antibiotic use, and vaccination) was not included in the risk analysis, as the companion animal shops in Al-Nasiriyah did not have such information. Additionally, it was challenging to collect the nasal swabs from the pets in animal shops repeatedly at regular intervals, as the ones present during one visit might not be present in the next. Thus, the dynamics of colonization over time were not determined.

CONCLUSION

Based on this study’s results, companion animals constitute a significant public health threat. They may contribute to spreading pathogenic S. aureus from one household to another, increasing the occurrence of MRSA in the community. The companion animals’ shops may represent epicenters for spreading MRSA and should be included in MRSA control and prevention programs.