INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that affects 2–4% of the global population (1). Clinically, psoriasis is characterized by red plaques with silvery scales (2). These features are associated with hyperproliferative keratinocytes and parakeratosis, indicating the presence of cell nuclei within the stratum corneum (3). In addition to these epidermal changes, psoriasis is accompanied by inflammatory dermal activity, represented by the infiltration of innate and adaptive immune cells (4). Chronic activation of the immune system and release of inflammatory cytokines in psoriasis result in damage to multiple tissues beyond the skin (5). Patients with psoriasis often exhibit inflammatory conditions affecting the joints, intestine, and central nervous system (6). Notably, metabolic syndrome—including obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia—is one of the most significant comorbidities in patients with psoriasis (5).

Metabolic syndrome-associated changes, such as increased production of inflammatory cytokines, adipocytokine secretion from adipose tissue, and intestinal microbiota dysbiosis, are potential pathological mechanisms linking metabolic syndrome and psoriasis (7, 8). Notably, these changes are primarily influenced by unhealthy diets high in fat and sugar (9). In mice, a high-fat diet (HFD) containing saturated or trans-unsaturated fatty acids is widely used to induce obesity (10). Although containing less fat than an HFD, a typical Western diet (WD) is rich in fats and simple sugars that include sucrose (9). Accumulating evidence has independently demonstrated the exacerbation of psoriatic skin inflammation by various types of diets, including those high in fat, fat and sugar, and saturated fatty acids (9, 10, 11, 12). However, no comprehensive analysis has fully addressed the inflammatory responses in the skin and intestine according to these diet types, which critically influence these tissues.

In this study, we examined the effects of HFD- and WD-induced inflammatory changes in the skin and small intestine using a murine model of psoriasis induced by topical application of imiquimod (IMQ). We assessed inflammatory responses in the skin, measured serum levels of inflammatory mediators, and analyzed immune environment changes in the small intestine. To gain insight into how different types of diets influence inflammatory responses in the skin, we compared transcriptomic changes in the skin lesions of mice with psoriatic inflammation following HFD or WD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 male mice purchased from Orient Bio (Gyeonggi-do, Korea) were maintained at standard temperature and humidity in a specific pathogen-free environment. All procedures involving mice were reviewed and approved by the Center of Animal Care and Use of the Lee Gil Ya Cancer and Diabetes Institute, Gachon University (Approval number: LCDI-2020-0113). Mice were fed one of three diets for 12 weeks. The HFD contained 60 kcal% from fat, 20 kcal% from carbohydrate, and 275.2 kcal from sucrose (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA). The WD contained 58 kcal% from fat, 25.5 kcal% from carbohydrate, and 700 kcal from sucrose (Research Diets). The standard chow diet contained 24.6 kcal% from fat, 54.6 kcal% from carbohydrate, and 12.72 kcal from sucrose (LabDiet, St. Louis, MO, USA). After 12 weeks, fasting glucose levels were measured using a glucometer (Allmedicus, Kyunggi, Korea) following fasting for 18 h. At sacrifice, blood samples, skin, perigonadal adipose tissue, spleen, small intestine, and cecal contents were collected for subsequent analyses.

Animal model of experimental psoriasis

A topical dose of 62.5 mg IMQ cream (5%, Aldara™; 3M Pharmaceuticals, Maplewood, MN, USA) or vehicle cream (Vaseline; Unilever, Rotterdam, Netherlands) was applied to the shaved back of mice for 5 days. Mice were assessed daily for changes in body weight. Transepidermal water loss (TEWL) was measured on the back skin using a Tewameter TM210 instrument (Courage + Khazaka GmbH, Cologne, Germany). Erythema and scaling were scored independently from 0–3 (0, none; 1, slight; 2, moderate; 3, marked).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

A Quantikine Mouse CD14 ELISA Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used to measure the serum levels of soluble CD14 (sCD14) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Absorbances of sCD14 were measured at 450 nm using the VICTOR X4 instrument (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

RNA was isolated from the skin and small intestine of mice using QIAzol and purified using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The purified RNA was processed with DNase I (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) to remove genomic DNA. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using an iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Quantitative PCR was performed using iQ SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) on a CFX Connect™ real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Relative gene expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (Gapdh) served as an invariant control. The primer sequences are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Microbiota analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from fresh or frozen cecal contents using the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Kit (Qiagen). The amounts of 16S rRNA gene sequences for each bacterial phylum were quantified by real-time PCR analysis and normalized to the total amount of eubacterial 16S rRNA genes in the sample. The primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

RNA extraction, library construction, and sequencing

Total RNA concentration was calculated using Quant-IT RiboGreen (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). To determine the percentage of RNA fragments > 200 bp (DV200), samples were analyzed on the TapeStation RNA screentape (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), with a DV200 value ≥ 50%. A total of 100 ng of total RNA was used for sequencing library construction, employing the SureSelectXT RNA Direct Library Preparation Kit (Agilent). The human exonic regions were captured using the SureSelect XT Mouse All Exon Kit (Agilent). Indexed libraries were submitted for sequencing on a NovaSeqX platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), with paired-end sequencing performed by Macrogen (Seoul, Korea).

Sequence annotation and statistical analysis of gene expression

Raw reads were preprocessed to remove low-quality and adapter sequences. The processed reads were aligned to the mm10 mouse genome reference using HISAT v2.1.0. Subsequently, aligned reads were assembled into transcripts using StringTie v2.1.3b, and their abundance was estimated. Genes with read counts of zero in one or more samples were excluded. Principal component analysis (PCA) plots were generated to confirm the similarity of expression among the samples. The statistical significance of the differential expression data was determined using the nbinomWaldTest with DESeq2. Significant gene list was filtered by |fold change| ≥ 2 and raw p-value < 0.05. All data analyses and visualizations of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were performed using R 4.2.2 (www.r-project.org).

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

GSEA was performed using the GSEA v4.3.2 software provided by the Broad Institute (Cambridge, MA, USA) as previously described (13). Enrichment analysis was performed using the hallmark gene sets from the MsigDB database. To determine the enrichment of ontology gene sets (C5.all.v2022.1), mouse gene symbols were remapped to human orthologs. Leading-edge analysis was performed to determine the overlapping gene sets. Selected gene sets with p < 0.05 and false discovery rate < 0.25 were considered.

Graphical illustrations

Schematics of experimental workflows were created using a licensed version of Biorender.com.

Statistical analyses

Data differences between groups were examined for statistical significance using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey post hoc or Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test. Multiple comparison tests were performed using a two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. GraphPad Prism 10.3.1 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for the data analyses.

RESULTS

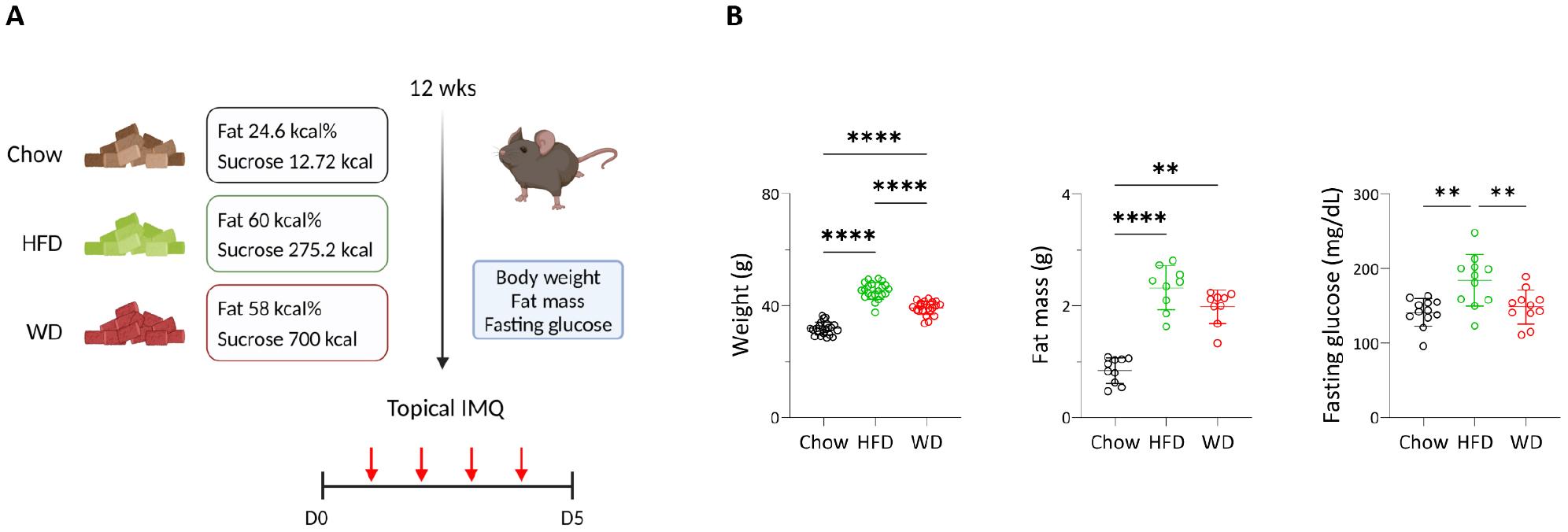

Diet-induced metabolic changes aggravate psoriatic inflammation

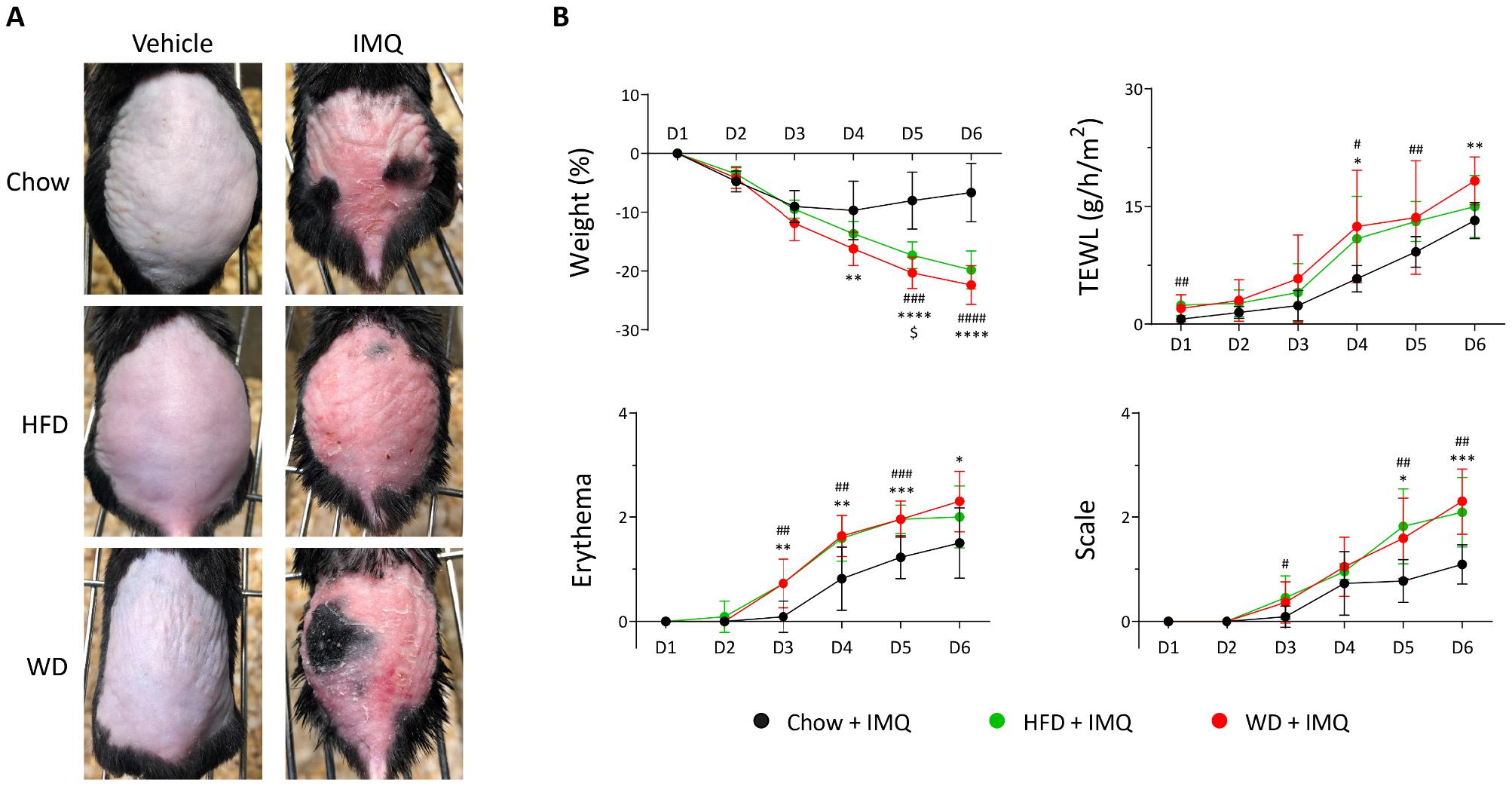

To induce metabolic changes, mice were fed either the HFD or WD for 12 weeks (Fig. 1A). Both diets increased body weight and perigonadal fat mass compared to the chow-diet-fed group, with greater weight gain in HFD-fed mice than that in WD-fed mice (Fig. 1B). Additionally, a significant increase in fasting glucose was observed only in the HFD-fed group, indicating that obesity-associated metabolic changes were predominantly induced by the high-fat content. The mice were subsequently topically treated with IMQ (Fig. 1A) to induce experimental psoriatic dermatitis (14). Erythema and scaling were evident in all diet groups (Fig. 2A). However, WD-fed mice showed a significant decrease in weight on day 5 of IMQ application, which was associated with an increased tendency for TEWL, erythema, and scale scores on day 6 (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 1

Obesity-associated profiles altered by diets. (A) Schematic of experimental psoriasis induced by imiquimod (IMQ) after 12 weeks of chow, high-fat (HFD), or Western diet (WD). (B) Body weight, fat mass, and fasting glucose values of mice. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. **p < 0.01 and ****p < 0.0001 using one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis test (fat mass).

Fig. 2

Clinical symptoms of psoriasis in mice treated with imiquimod (IMQ). (A) Photographs of skin lesions. HFD, high-fat diet; WD, western diet. (B) Weight changes, transepithelial water loss (TEWL), erythema, and scale of IMQ treated skin in mice (n = 11 per group). Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *, Chow IMQ vs. WD IMQ; #, Chow IMQ vs. HFD IMQ; $, HFD IMQ vs. WD IMQ. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 using two-way ANOVA.

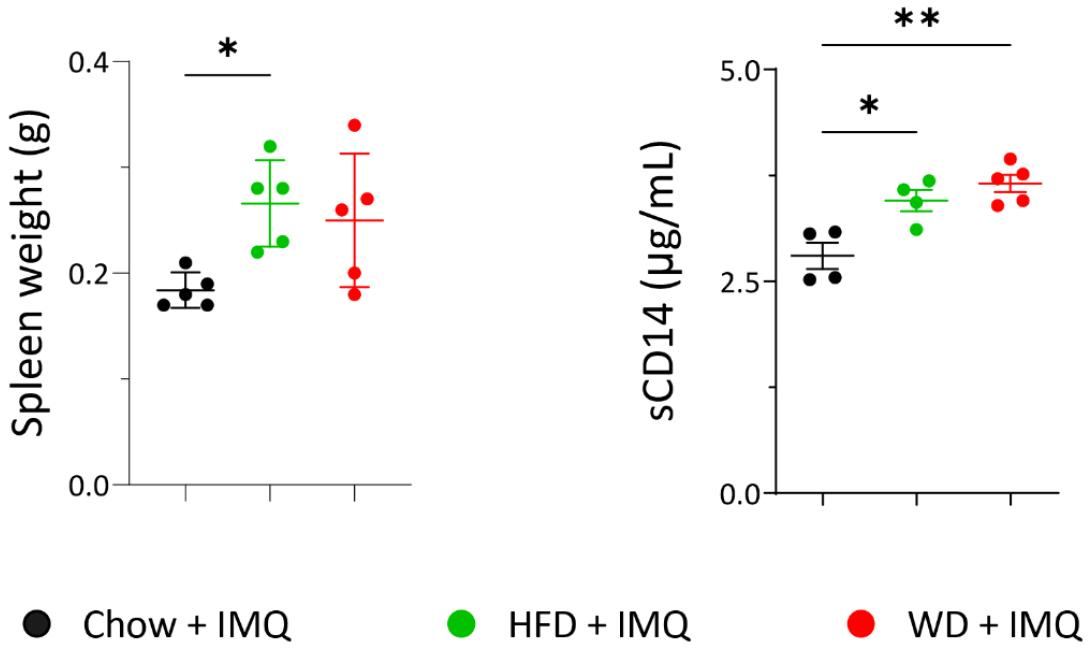

Systemic signs of inflammation are comparable between HFD- and WD-fed mice with psoriatic inflammation

Weight loss observed in IMQ treated mice is indicative of a systemic inflammatory response (14). As WD-fed mice exhibited an increased tendency of weight loss compared to HFD-fed mice, we assessed spleen weight as a reflection of systemic inflammation. Compared to chow-fed mice, spleen weights were increased in mice with experimental psoriasis fed either HFD or WD, with no significant differences between these two diets (Fig. 3). Patients with psoriasis have increased serum levels of sCD14 compared to healthy controls (15). Serum sCD14 levels are recognized as a marker linking inflammation between the skin and increased intestinal permeability (16). In mice with experimental psoriasis, serum sCD14 levels were increased by both HFD and WD (Fig. 3). Although the WD group showed the highest levels compared to the chow and HFD groups, no significant difference was observed between WD and HFD-fed mice. Collectively, these results indicate that both HFD and WD increased systemic inflammation in psoriatic mice compared to the chow diet. However, the extent of promoted systemic inflammation was not significantly different between these two diets.

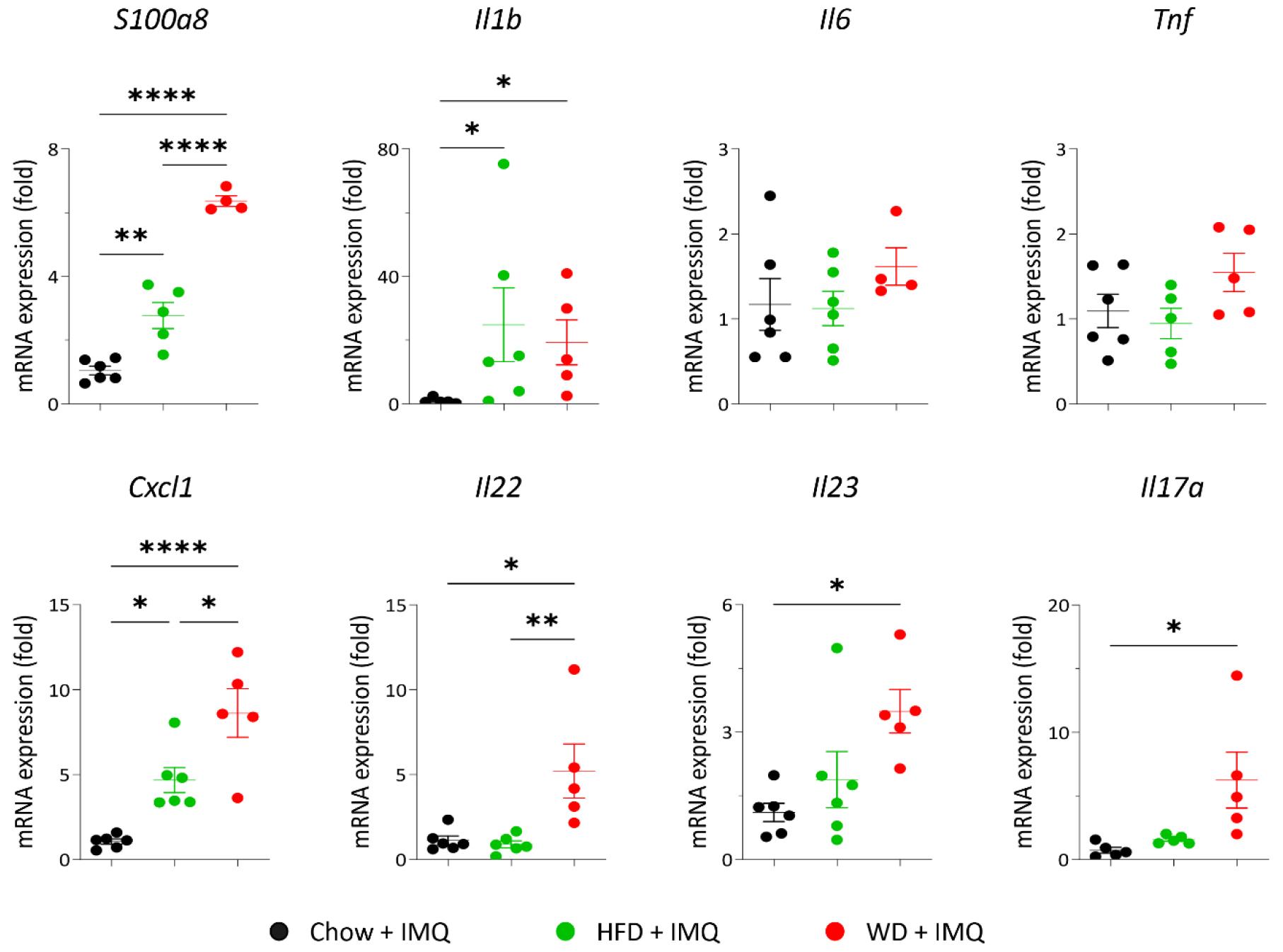

WD-fed mice exhibit increased expression of psoriasis-related inflammatory mediators compared to HFD-fed group

Our hypothesis that the type of diet affects localized inflammatory responses in the skin lesions of mice with psoriatic inflammation was addressed by examining mRNA expression of inflammatory mediators implicated in psoriasis pathology. Both HFD- and WD-fed mice with psoriatic inflammation showed a significant increase in the gene expression of innate immune mediators (S100a8 and Il1b), the chemokine responsible for neutrophil recruitment (Cxcl1), and the cytokine that is critical in psoriasis pathogenesis (Il22) compared to the chow-fed mice (Fig. 4). Notably, S100a8 and Cxcl1 expressions were significantly increased in the skin lesions of the WD group compared to that of the HFD group (Fig. 4). Additionally, significant increases in Il23 and Il17a expression, which are cytokines crucial for the initiation and progression of psoriasis, were observed only in the skin lesions of the WD-fed group compared to that of the chow diet-fed mice (Fig. 4). These results suggest that WD has a pronounced role in promoting psoriatic inflammation over other types of diets.

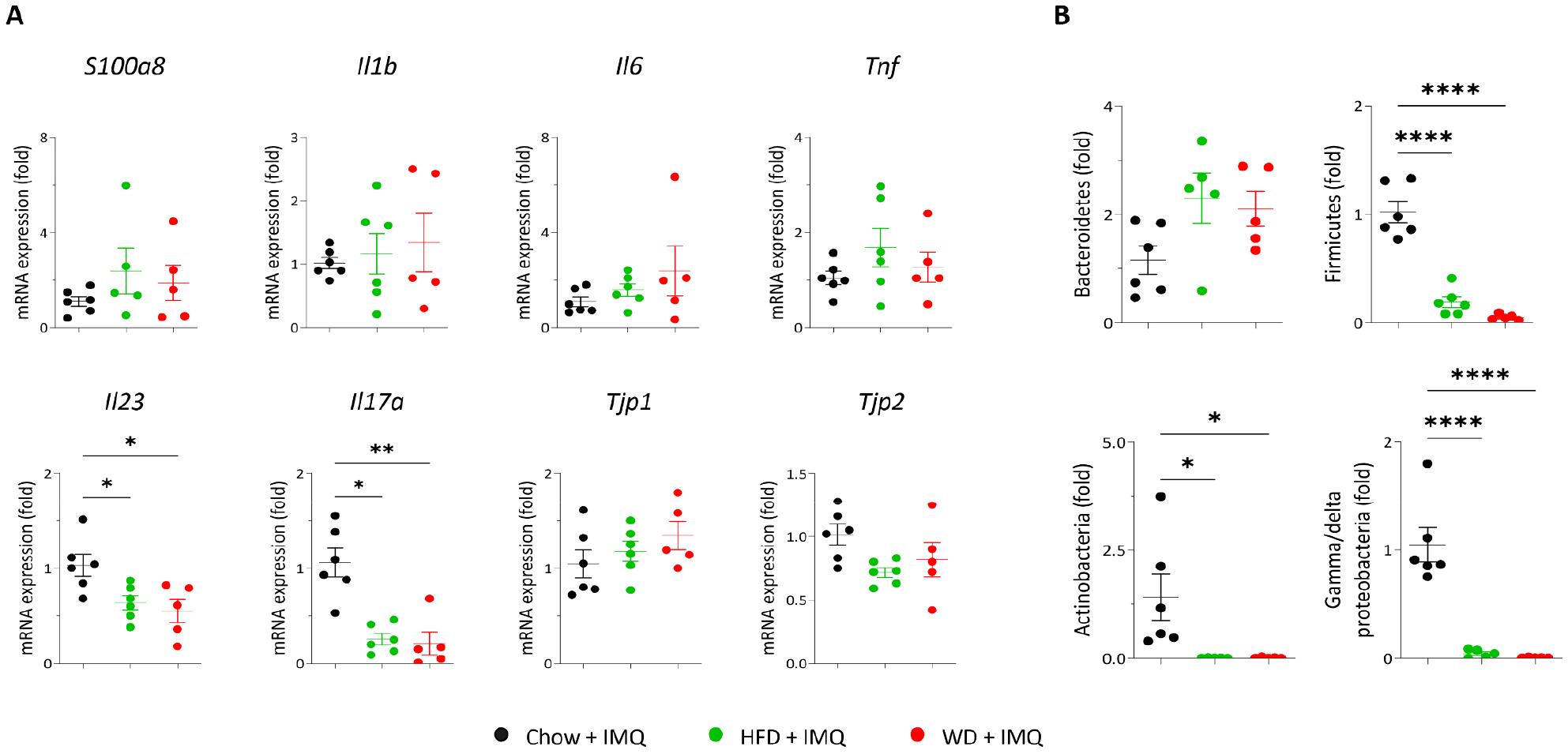

Small intestinal immune environments are comparable between HFD- and WD-fed mice with psoriatic inflammation

Absorption of nutrients occurs exclusively in the small intestine, where numerous immunocompetent cells reside (17). Additionally, increased permeability of the intestinal barrier amplifies inflammatory responses beyond the intestinal tract (18). Therefore, we analyzed whether the expression of inflammatory mediators and epithelial tight junction molecules in the small intestine of mice with psoriatic inflammation was affected by different diets. As shown in Fig. 5A, the expressions of innate mediators (S100a8, Il1b, Il6, and Tnf) and tight junction molecules (Tjp1 and Tjp2) were comparable among chow-, HFD-, and WD-fed groups. The HFD and WD groups showed decreased expressions of Il23 and Il17a compared to chow-fed mice, with no significant difference between the HFD and WD groups (Fig. 5A). Next, we assessed the luminal microbiome composition by performing real-time PCR analysis of bacterial phyla in fecal samples collected from the ceca. Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes are two major phyla of the stool microbiome (19). The proportion of Bacteroidetes remained unchanged by both HFD- and WD-fed groups (Fig. 5B). Both diets decreased the proportion of Firmicutes compared to the chow diet, with no significant differences between the two diet groups (Fig. 5B). The proportional changes observed for Actinobacteria and Gamma/delta proteobacteria were similar to those observed for Firmicutes (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5

Expression of inflammatory mediators and epithelial tight junction molecules in the small intestine. (A) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of the small intestine. (B) Quantitative PCR analysis of cecal microbiota. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 using one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis test (Il17a in A).

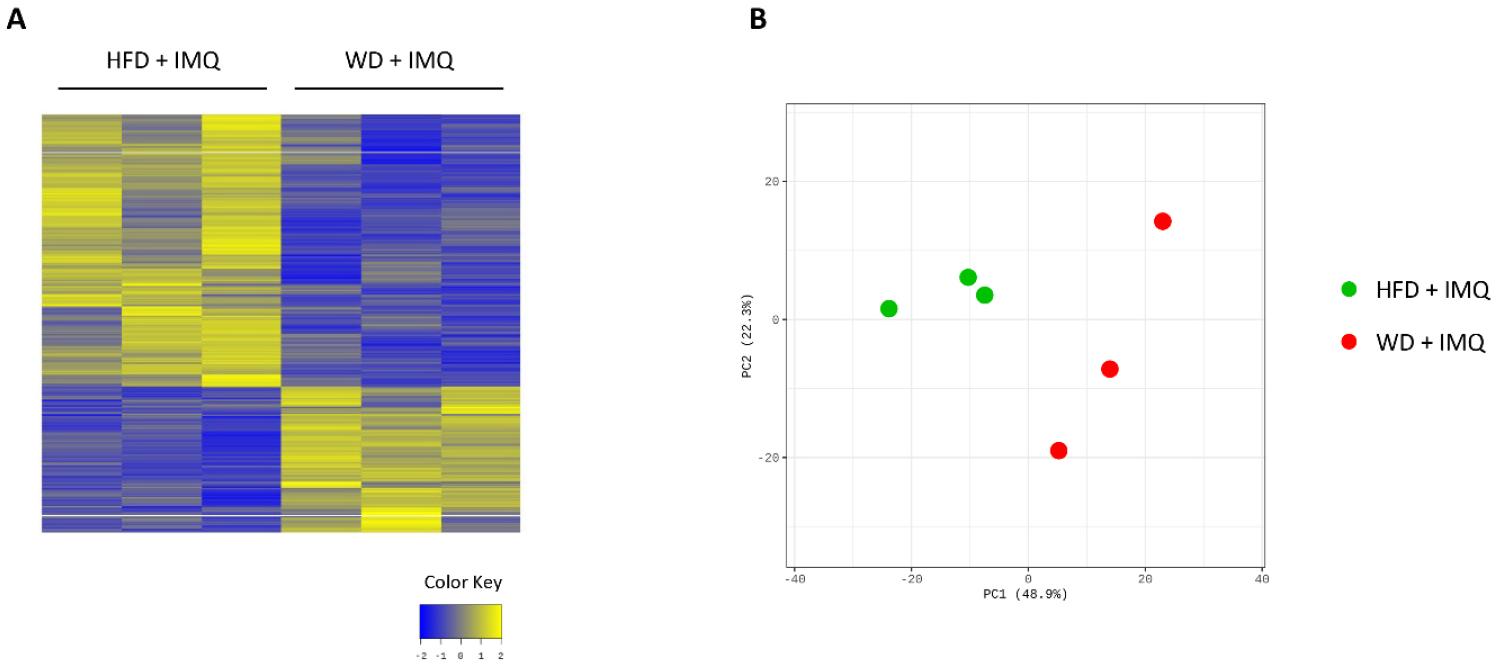

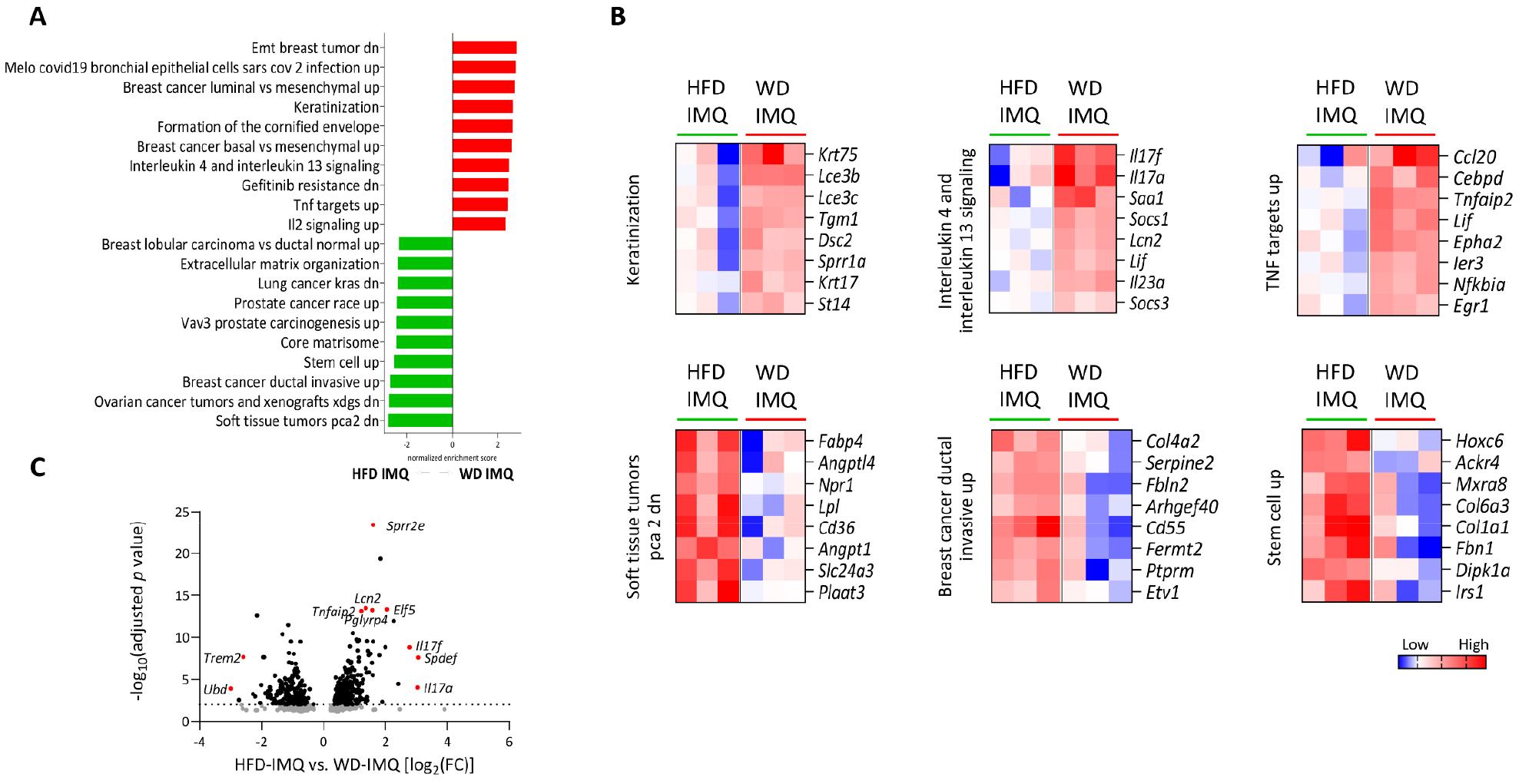

WD-fed mice with psoriatic inflammation exhibit differential transcriptomic changes in skin lesions compared to the HFD-fed mice

As WD-fed mice exhibited pronounced inflammatory changes in the skin compared to the HFD-fed mice, we compared transcriptome profiles of skin lesions between these two groups to better understand the details of inflammatory parameters influenced by diets. We identified 701 DEGs between the HFD- and WD-fed groups. Of these, 245 were upregulated and 456 were downregulated in WD-fed mice compared to that in HFD group (Supplementary Fig. 1A). PCA revealed marked differences between the two groups (Supplementary Fig. 1B). GSEA revealed enriched gene sets in HFD-fed mice associated with tissue microenvironment remodeling, including gene ontologies involved in cancer development, stem cell upregulation, and extracellular matrix organization (Fig. 6A). In contrast, enriched gene sets in WD-fed mice were associated with skin epithelial formation (keratinization and formation of the cornified envelope) and increased inflammation, such as interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 signaling, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) targets, and IL-2 signaling (Fig. 6A and B). Psoriatic inflammatory genes (Il17a and Il17f) and genes associated with epithelial cell differentiation and proliferation (Sprr2e and Spdef) were among the most upregulated genes in skin lesions of WD-fed mice (Fig. 6C). In contrast, the expression of Trem2, a gene associated with obese adipose tissue metabolism, was among the most significantly downregulated genes in these mice (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that WD triggers exacerbated inflammatory responses in psoriatic skin, while attenuating responses associated with obesity-induced microenvironmental changes, compared to HFD upon IMQ treatment.

Fig. 6

Differential transcriptomic changes in the skin. (A) Gene ontology terms enriched in the skin of high-fat diet (HFD)- and western diet (WD)-fed mice treated with imiquimod (IMQ) determined by gene set enrichment analysis. (B) Selected gene sets differentially expressed in the skin (adjusted p < 0.05). The heatmaps show the log2-fold change relative to the geometric mean fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments + 0.01. (C) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes between HFD- and WD-fed mice treated with IMQ.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that the WD induces markedly increased psoriatic inflammation compared to the HFD, even though both diets promote systemic inflammation and metabolic changes. Notably, HFD-fed mice showed greater weight gain and glucose intolerance. These findings challenge the prevailing understanding that HFD is the primary contributor to systemic inflammation and suggest that WD has unique properties that influence localized inflammatory processes, particularly in psoriatic skin lesions. Furthermore, our observations indicated that obesity alone is not sufficient to exacerbate psoriatic inflammation, highlighting dietary contents as a predisposition to accelerated psoriatic inflammation.

WD and HFD have critical differences in the composition of their nutritional content. WD typically includes high levels of sugar, processed carbohydrates, and fat, whereas HFD predominantly focuses on a high-fat content. The inclusion of refined sugars and processed components in the WD may contribute to greater systemic stress, potentiating skin inflammation. High sugar intake exacerbates inflammatory pathways by promoting systemic inflammation via activation of nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat protein-3 and IL-1β (20), potentially inducing neutrophil chemoattracts, such as chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (9, 21), as evidenced by the increased expression of S100a8 and Cxcl1 in WD-fed mice than that in HFD-fed mice. Additionally, the high glycemic index of WD leads to a rapid rise in blood glucose (22), resulting in insulin resistance and altered lipid metabolism. These changes may synergistically contribute to the increased severity of psoriasis (23).

Another notable observation was the differential gene expression in skin lesions between WD- and HFD-fed groups, with WD-fed mice exhibiting enrichment in gene sets related to keratinization and formation of the cornified envelope. Psoriasis is characterized by pronounced papulosquamous epithelial changes due to abnormal keratinocyte differentiation and accelerated turnover (24). The enrichment of pathways related to keratinization indicates that WD may directly impact defective keratinocyte cycles by promoting hyperproliferation and abnormal differentiation, potentially through altered lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, which affects skin barrier function. The transcriptomic analysis further highlighted that WD-fed mice had a more profound upregulation of gene sets involved in inflammatory pathways, such as IL-4, IL-13, TNF targets, and IL-2 signaling. These findings suggest that WD triggers broader immune activation, which may be responsible for exacerbating psoriatic lesions. The increased production of inflammatory mediators may also facilitate a more potent inflammatory response, contributing to impaired skin barrier function and increased susceptibility to inflammation. Interestingly, while both HFD and WD increased systemic markers of inflammation, such as spleen weight and serum sCD14, no significant differences were observed between the two diets, suggesting that the heightened psoriatic inflammation in WD-fed mice involves localized factors rather than an increase in systemic inflammation. This further suggests that specific components of WD may more effectively disrupt skin homeostasis, leading to increased sensitivity and exaggerated inflammatory responses. One such component could be advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), which are characterized by covalent bonds between a reduced sugar and a free amino group. AGEs are abundant in the WD and have a prominent capacity to induce oxidative stress and tissue damage, thereby promoting inflammatory responses (25, 26). Additionally, WD-induced dysregulated bile acid signaling contributes to cutaneous inflammation by inducing T helper type 17-mediated skin inflammation (11, 27).

The role of the gut-skin axis may also be crucial in explaining the differential impacts of WD and HFD. Increased intestinal permeability, influenced by dietary composition, can lead to systemic endotoxemia, which has been linked to skin inflammation. WD induces a shift in gut microbiota composition, enhancing susceptibility to bacterial infection and intestinal inflammation (28). However, we observed no significant differences in the intestinal immune environment or microbiome composition between the WD and HFD groups. Additionally, intestinal expression of inflammatory mediators and epithelial junctional molecules was comparable between these two groups, suggesting that while gut permeability may contribute to systemic inflammation, the localized effects of WD on skin inflammation probably involve additional mechanisms independent of gut immune environmental changes.

Overall, our data suggest that the WD exacerbates psoriatic inflammation due to a combination of factors, including increased metabolic stress, alterations in keratinocyte differentiation, and upregulation of skin-specific inflammatory pathways. These findings emphasize the need for considering dietary components beyond fat content alone when evaluating diet-induced exacerbation of inflammatory skin conditions such as psoriasis. Future studies should focus on elucidating specific components of WD that drive these changes and exploring potential interventions to mitigate diet-induced inflammatory responses in psoriasis.