INTRODUCTION

Patient treatment and infection control have become difficult due to the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogenic Pseudomonas species in hospitals worldwide. Pseudomonas species are commonly found in the environment, as they are effective in colonizing various niches, including medical devices, the respiratory system, wounds, and the urinary tract. They can cause a wide range of infections, ranging from moderate to severe, with significant death rates (1, 2). MDR Pseudomonas species are especially hazardous in clinical settings because of their capacity to develop resistance to many classes of antibiotics. P. aeruginosa, in particular, is a prominent opportunistic pathogen with both intrinsic and acquired resistance features; it is the cause of healthcare-associated infections worldwide that tend to complicate treatment options (3). The introduction and dissemination of MDR Pseudomonas species, such as P. fluorescens and P. putida, causes therapeutic problems, necessitating ongoing surveillance and the development of novel therapeutic techniques (4).

Pseudomonas sp. acquire MDR mechanisms through chromosomal mutations, acquiring mobile genetic elements containing resistance genes (5) efflux pumps, enzymatic antibiotic modification, and changes in membrane permeability. These mechanisms impart resistance to beta-lactams, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and other routinely used antibiotics (6). The capacity of Pseudomonas species to produce biofilms can also impart resistance by shielding the bacteria from medicines and immunological responses, resulting in chronic infections and persistence in medical equipment and hospital settings (7). The increase in the number of MDR Pseudomonas species has made antimicrobial resistance a global public health concern by undermining the effectiveness of treatment in various contexts. MDR Pseudomonas bacteria have been found in various environmental reservoirs, including household water supplies (8). These reservoirs pose serious health hazards to humans due to the possibility of ingestion, inhalation, or skin exposure (9, 10). MDR Pseudomonas contamination in household water supplies is especially serious in rapidly expanding cities such as Dhaka, Bangladesh, where infrastructure development cannot keep up with population growth. Selective pressure from antimicrobial drugs and environmental conditions, such as temperature and salinity, promote the dissemination of resistance determinants among bacteria in water systems (6, 11, 12). Because of poor sanitation, sporadic water supplies, and fluctuating water quality standards, household water sources in urban environments may harbor MDR Pseudomonas species (13).

Developing successful methods to mitigate water contamination requires an understanding of how environmental factors affect the prevalence and behavior of MDR Pseudomonas species in household water supplies. For example, temperature can affect the rates of bacterial growth and metabolic processes, which may influence survival strategies and the genetic exchange of resistance genes in water systems (11). Similarly, high NaCl concentrations can favor salt-tolerant bacterial strains and change their antibiotic resistance profiles. Such concentrations are frequently found in urban water systems as a result of pollution or disinfection procedures (6, 12, 14)

Herein, we examined the reaction of different Pseudomonas species from Dhaka household water samples to various levels of NaCl, pH, and temperature and characterized their drug resistance profiles. This study aims to develop specific interventions to protect public health and water quality in urban areas worldwide by clarifying the relationship between environmental conditions and antibiotic resistance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of samples: We collected 10 samples (50 ml each) from various sites throughout Dhaka city. Samples were placed in sterile containers and promptly transported to the laboratory for bacterial detection. After 10-fold serial dilutions 0.1 ml inoculum was placed on cetrimide agar (Merck, Germany).

Biochemical studies of isolates: Selected colonies were characterized using standard physiological and biochemical tests (15, 16, 17).

Growth response of isolates to different NaCl concentrations: We assessed the isolates’ growth responses to various concentrations of NaCl according to a standard protocol (15). Briefly, we used nutrient broth (HiMedia Laboratories, Peptone 5 g/L, Sodium chloride 5 g/L, HM peptone B 1.5 g/L, Yeast extract 1.5 g/L, pH –7.4±0.2 ) supplemented with NaCl at concentrations of 0.9%, 2%, 5%, 7%, and 10%. Test tubes of broth were inoculated with a 24-h bacterial culture and incubated at 37°C for 12 h, and we measured the absorbance of the cultures (18) at 600 nm using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, UV-120-02, Japan).Each culture underwent serial dilution, resulting in optical density values between 0.200 and 0.700. Selected OD600 values were further serially diluted (from 10−2 to 10−5), plated onto Petri dishes containing sterile cetrimide agar media , and counted following the standard methods (16).

Growth response of isolates at different temperatures: We measured the effects of temperature on the growth of the isolates following a standard protocol (15). Briefly, we prepared nutrient broth in tubes and inoculated these with the isolates and allowed them to grow at the following temperatures for 48 h: 4°C, 10°C, 30°C, 40°C, 50°C, and 55°Cfor 12 h in a rotating incubator. Absorbance was measured at 600 nm using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, UV-120-02, Japan) (18). Each culture underwent serial dilution, resulting in optical density values between 0.200 and 0.700. Selected OD600 values were further serially diluted (from 10−2 to 10−5), plated onto Petri dishes containing sterile cetrimide agar media, and counted following the standard methods (16).

Growth response of isolates at different pH levels: We measured the growth response of the isolates to different pH levels using peptone water broth (Peptone 10 g/L, Sodium Chloride 5 g/L) (in 4:1 ratio) buffered to a pH range of 5.7–6.8. The pH of the buffer solutions was checked after preparation. The medium pH was adjusted with 0.1 mol/L HCl or 0.1 mol/L NaOH as needed at each step, and the cultures were incubated for 12 h in a rotating incubator at 37°C. Absorbance was measured at 600 nm using a Shimadzu UV-120-02 spectrophotometer (18). Each culture underwent serial dilution, resulting in optical density values between 0.200 and 0.700. Selected OD600 values were further serially diluted (from 10−2 to 10−5), plated onto Petri dishes containing sterile cetrimide agar media, and counted following the standard methods (16).

Sequence-based identification of isolates: The isolates were conventionally identified based on their morphological; biochemical and physiological characteristics, and their identities were confirmed via molecular identification through 16S rDNA sequencing. The primer pair used to amplify a portion of the 16S rRNA gene consisted of 5ʹ-16S rRNA: CCAGACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGC and 3ʹ-16S rRNA: CTTGTGCGGGCCCCCGTCAATTC. Template DNA was obtained from the supernatant of heat-lysed cell suspensions. The PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation for 5 min at 95ºC, followed by 30 x cycles of 1 min at 94ºC, 30 s at 55ºC, and 1 min at 72ºC for extension; followed by 10 min at 72ºC for the final extension. A UV transilluminator was used to visualize the DNA bands, which were recorded using a gel documentation system (Microdoc DI-HD, MUV21-254/365, Cleaver Scientific). Automated PCR product sequences along with those of related organisms were evaluated through homologous sequence alignment using the NCBI-BLAST database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and rRNA BLAST (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/cgi-bin/rRNA/blastform.cgi) tools.

Determination of resistance to antibiotics: The Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion test was used to assess the susceptibility or resistance of anaerobic and aerobic pathogenic bacteria to different antimicrobial agents. We cultured our isolates on Mueller–Hinton agar (HiMedia Laboratories Private Limited) with various antibiotic-impregnated filter paper disks. The presence or absence of growth around the disks is an indirect indicator of the compound’s effectiveness in inhibiting the organism (19). We measured the zones of inhibition after 24 h of incubation at 37°C, and isolates were categorized as susceptible (S), intermediately resistant (I), and resistant (R) based on the guidelines of the (20). Isolates classified as MDR were those that withstood at least one antimicrobial agent across three or more categories (21). The different antibiotics used in this study and their zone interpretive chart are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antimicrobials and their interpretive zone (inhibition zone diameter in mm)

RESULTS

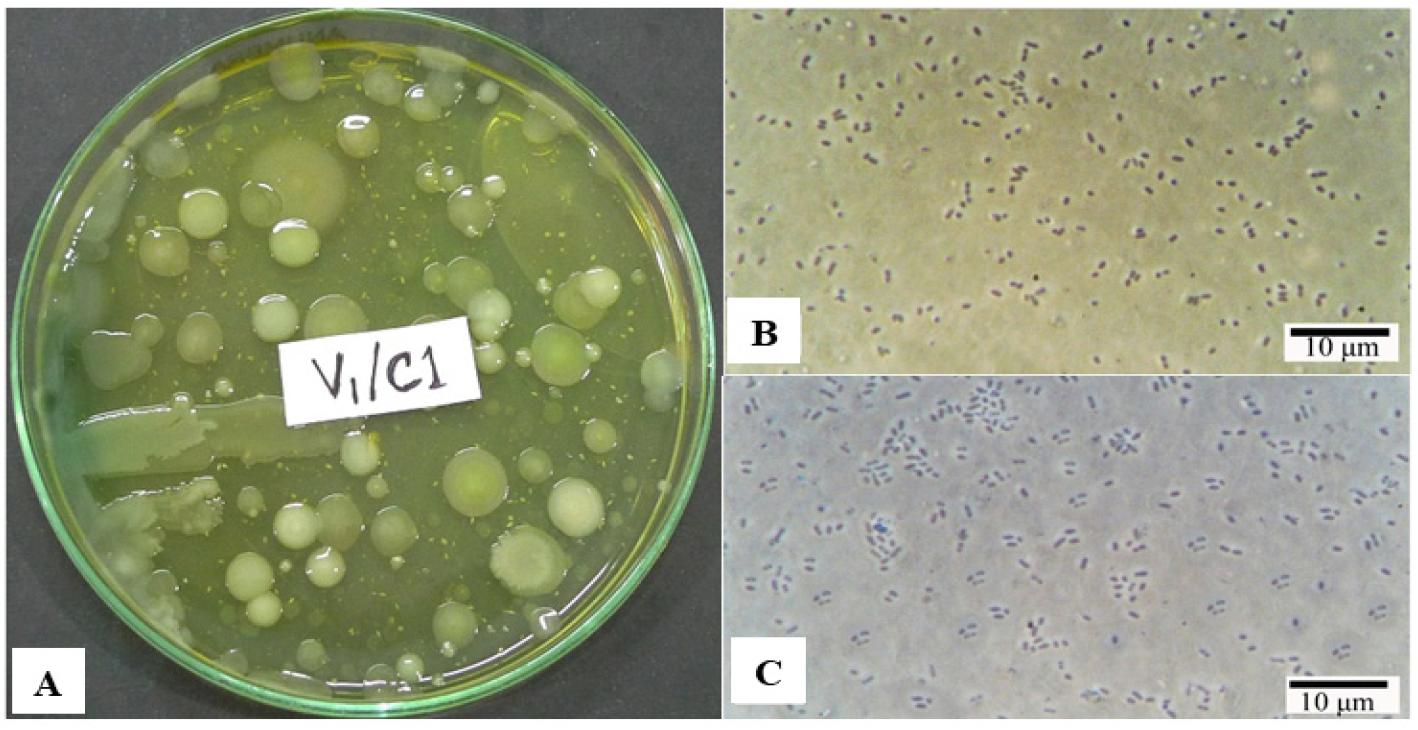

Bacterial load and morphological characteristics: The bacterial load of samples varied from 2.0 × 103 to 6.2 × 103 CFU/mL on cetrimide agar. We selected 80 colonies and purified them for further analysis and identification. The surface characteristics of the bacterial colonies were found to be smooth, concentric, and contoured. Their optical characteristics were both opaque and translucent. We selected colonies visually based on their yellowish-green or light green color. The margins of the selected colonies were entire and smooth, and their elevation was convex and raised (Fig. 1A). The cells had no spores and were mostly short rods with rounded ends that occurred singly. The cell dimensions were 1.2–1.8 × 0.6–0.8 µm (Fig. 1B-C). The results of the major biochemical tests conducted on the isolates are presented in Table 2.

Fig. 1

Isolation and Microscopic observation. (A) Growth on Cetrimide agar plate (B-C) Photomicrographs showing the selected isolates’ vegetative cells under phase contrast microscope.

Table 2.

Biochemical test results of isolates

“+” sign indicates catalase activity positive, H2S produced in Kligler’s Iron Agar (KIA), motile, indole produced, urease produced, citrate utilized, methyl red (MR) positive, Voges–Proskauer (VP) positive, starch hydrolyzed, oxidase activity positive, lecithinase produced, A = acid (yellow), K = alkaline (red) reaction, SA = strict aerobes, FA = facultative anaerobes.

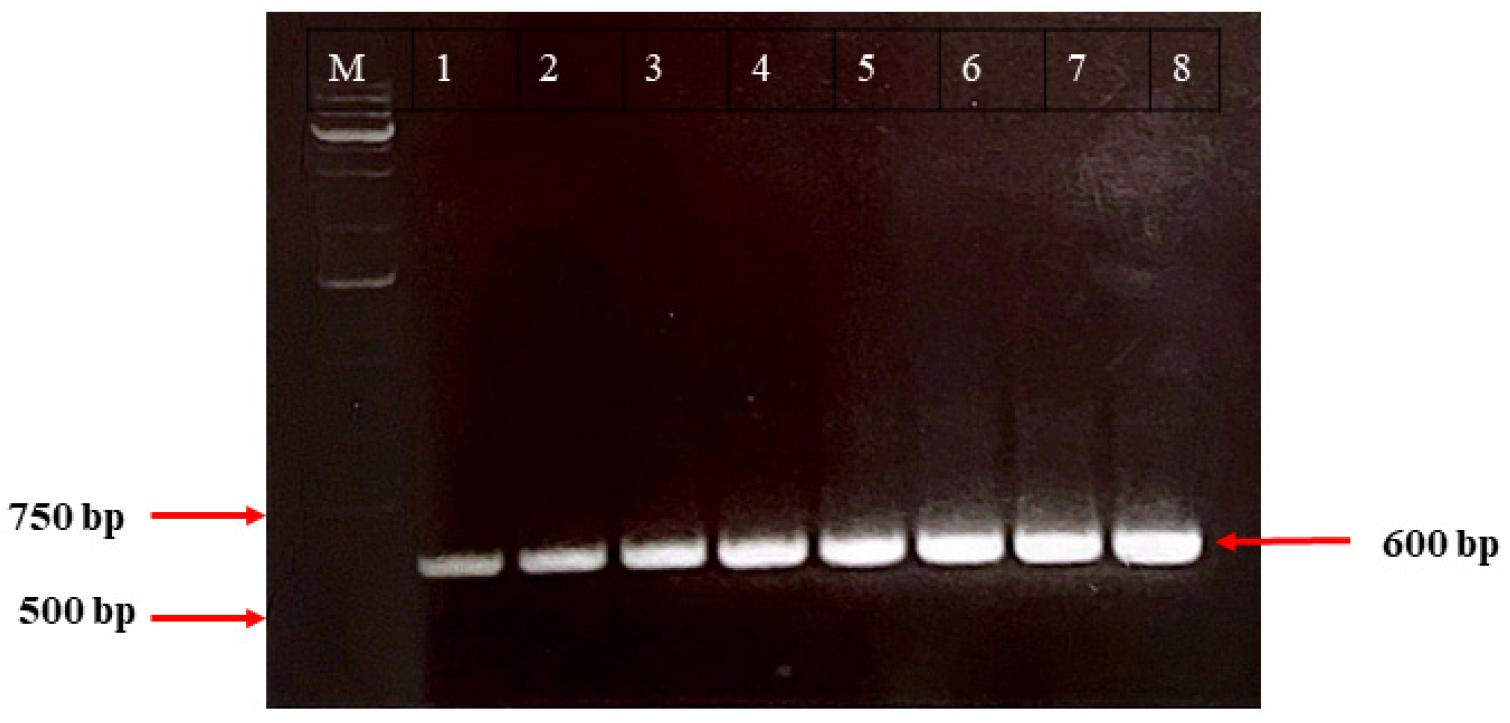

Molecular identification of the isolates: Universal primers were used to amplify the 16S rRNA gene from unknown bacterial isolates (Fig. 2), which was then gel-purified and sequenced. According to BLAST and rRNA BLAST searches, the major Pseudomonas species in our samples were P. syringae, P. aeruginosa, P. mendocina, P. oleovorans, P. guguanensis, P. viridiflava, P. fluorescens, and P. protegens. Table 3 shows the distribution, relative abundance, and diversity of Pseudomonas species in the sample set. P. aeruginosa, P. syringae, and P. mendocina accounted for a large proportion 13%, 14% and15% of the isolates respectively. The presence of these different species in household water suggests a diversified Pseudomonas population in the Dhaka samples.

Fig. 2

Partially amplified 16S rRNA gene by PCR. Lanes 1 to 8 correspond to the eight distinct bacterial isolates. Lane M is a 1.0 kb ladder. The amplified DNA band on the gel was approximately 600 bp in size.

Table 3.

Distribution pattern of Pseudomonas species in the sample set

| SI.NO. | Name of isolates | Number of isolates | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | P. syringae | 14 | 17.5 |

| 2. | P. mendocina | 12 | 15 |

| 3. | P. oleovorans | 7 | 8.75 |

| 4. | P. guguanensis | 9 | 11.25 |

| 5. | P. aeruginosa | 13 | 16.25 |

| 6. | P. protegens | 7 | 8.75 |

| 7. | P. fluorescens | 8 | 10 |

| 8. | P. viridiflava | 10 | 12.5 |

| Total | 80 | 100 | |

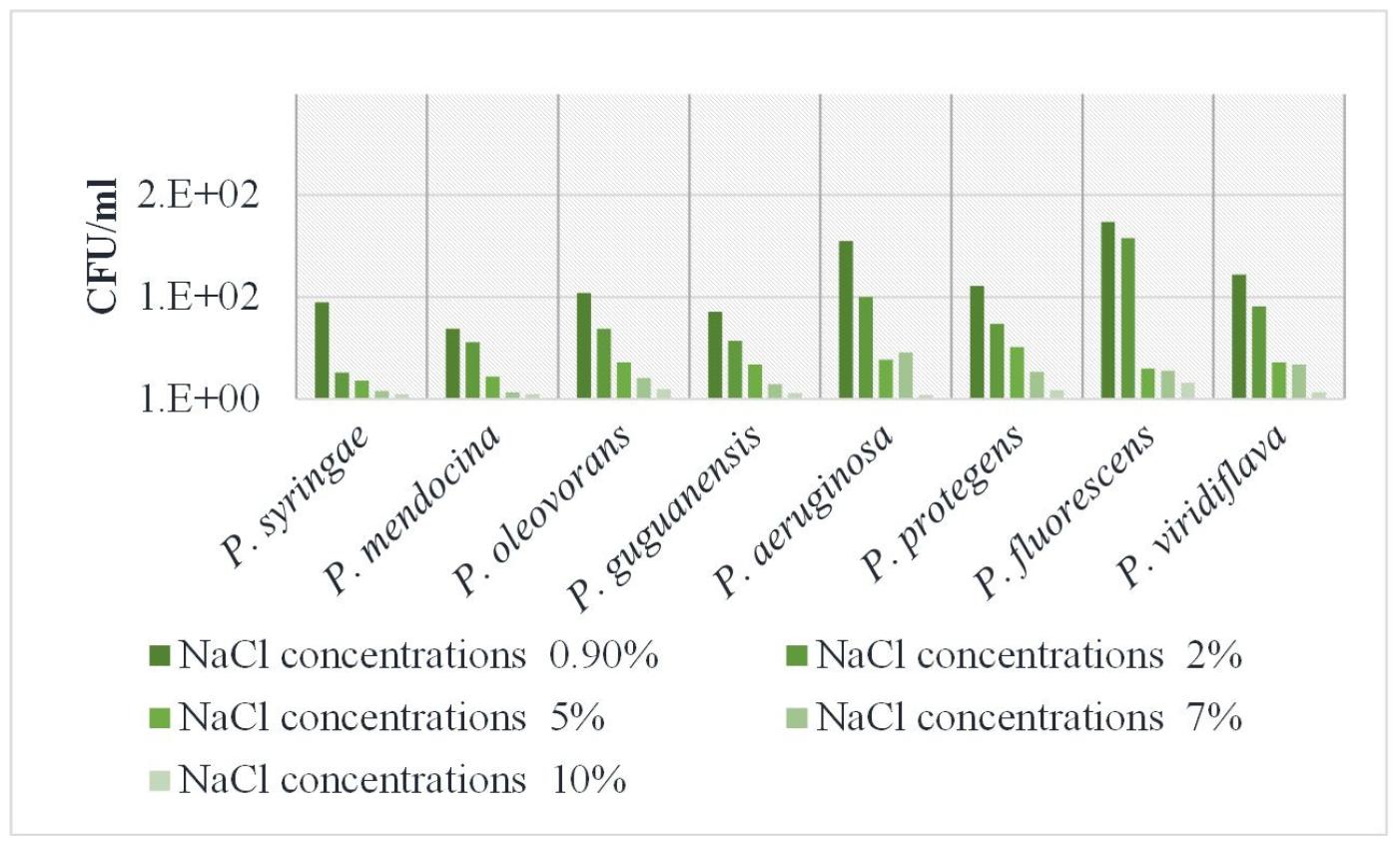

Bacterial growth responses to varying NaCl concentrations: The responses of Pseudomonas species to various NaCl concentrations (2%, 5%, 7%, and 10%) were compared to that of standard saline concentration (0.9% NaCl). Higher concentrations (7% and 10%) of NaCl suppressed growth, indicating that these concentrations were inhibitory (Fig. 3). Overall, the results show variable levels of salt tolerance among the bacterial isolates to increasing NaCl concentrations. P. fluorescens was the most salt-tolerant, retaining high measurement of cell abundance even at high NaCl concentrations. P. aeruginosa tolerated low NaCl concentrations but exhibited a considerable reduction in growth as salt concentrations increased. P. protegens and P. oleovorans displayed intermediate NaCl tolerance, with decreasing growth values as salt concentrations increased; however, these values were higher than many other isolates. P. guguanensis and P. mendocina were moderately sensitive to salt. P. syringae and P. viridiflav a were the most salt-sensitive, with both showing significantly less growth at increasing NaCl concentrations, particularly 10% NaCl. Overall, the data show that the growth or activity of all isolates decreased with increasing salt content, with considerable variability in the level of salt tolerance across the bacterial isolates. These findings highlight the diverse strategies employed by Pseudomonas species to adapt to saline environments, which enable them to occupy their biological niche and that suggests the possibility of applications in biotechnology.

Fig. 3

Effect of different NaCl concentrations on the growth of bacterial isolates. Growth response of different Pseudomonas species in nutritional broth with NaCl concentrations of 0.9, 2, 5, 7, and 10% after 24 hours of growth.

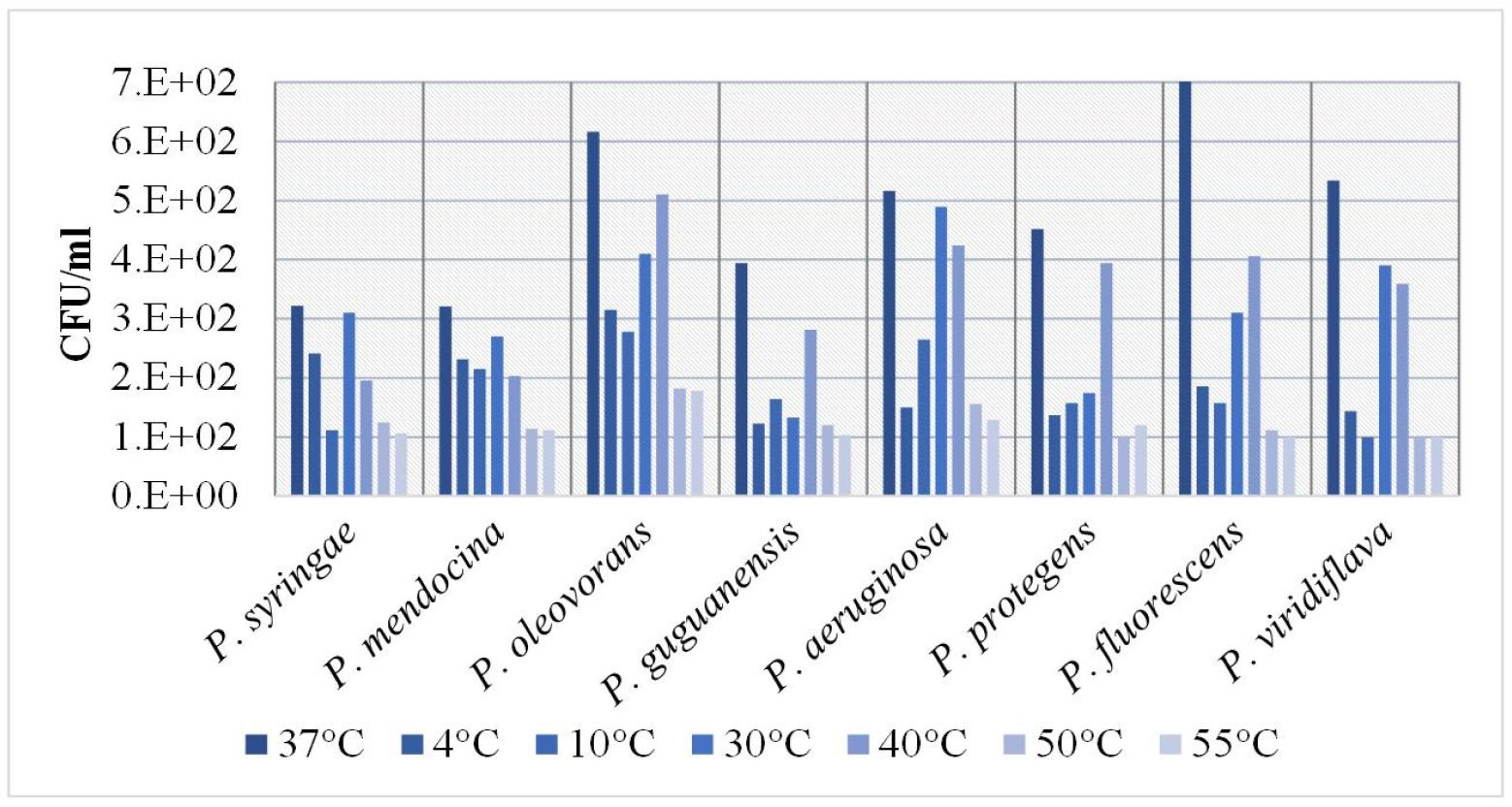

Temperature-dependent growth responses of variousPseudomonasspecies: We compared the growth responses of different Pseudomonas species to temperatures ranging from 4°C to 55°C to those at 37°C. P. syringae grew well at both 4°C and 37°C, with the greatest value at 37°C, demonstrating that this strain thrives in a wide range of temperatures; however, it grew best at higher temperatures. The growth rates of P. viridiflava decreased at intermediate (10°C) and high (40°C, 50°C, 55°C) temperatures. P. mendocina exhibited similar growth rates in all tested temperatures, although we observed a slight preference for lower (4°C and 10°C) temperatures and slightly reduced growth at higher (40°C, 50°C and 55°C) temperatures. P. oleovorans grew best at 37°C, although it also grew well at 4°C, 10°C, 30°C, and 40°C. However, its growth rate decreased substantially at higher (50°C and 55°C) temperatures. P. guguanensis grew best at 30°C and 37°C; beyond these temperatures, its growth was substantially slower. P. aeruginosa grew well at temperatures ranging from 30° to 40°C, whereas its growth at lower temperatures was intermediate. P. protegens preferred a temperature of approximately 40°C. P. fluorescens and P. viridiflava grew best at 30°C and 40°C (Fig. 4). Overall, we found that all strains had reduced growth at temperatures other than 37°C, which implies that these bacteria are less suited to harsh temperatures. Therefore, temperature is an environmental component that significantly affects microbial dynamics.

Fig. 4

Effect of different temperatures on the growth of bacterial isolates. Growth response of different Pseudomonas species in nutritional broth grown at different temperatures (37, 4, 10, 30, 40, 50 and 55°C) after 24 hours of growth.

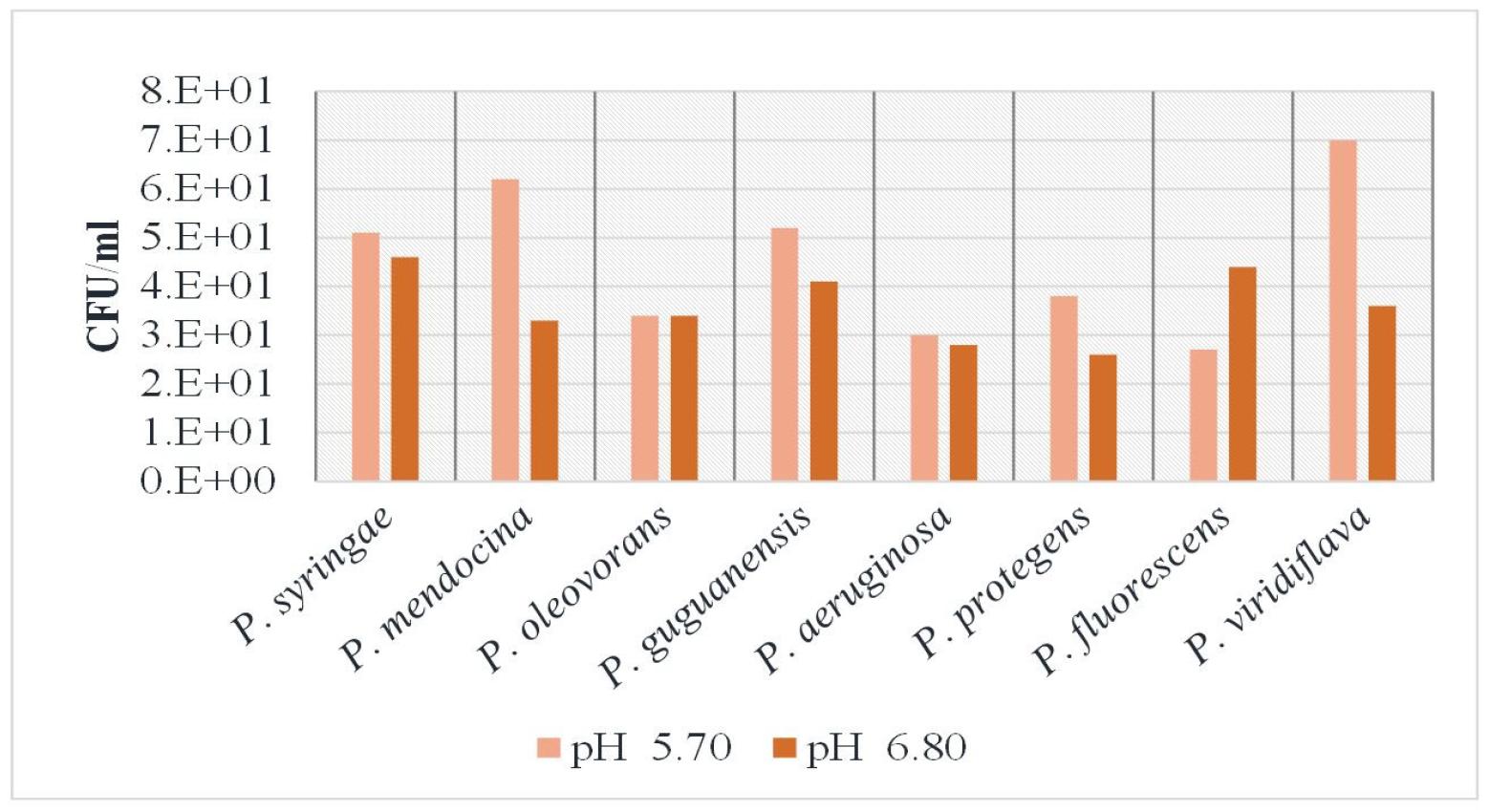

Growth responses of variousPseudomonasspecies to different pH levels: We observed that different bacterial species reacted to different pH levels in different ways, i.e., some species declined while others increased their growth response as pH levels changed (Fig. 5). Specifically, P. mendocina exhibited a considerable decrease in growth at higher pH levels.

Fig. 5

Effect of different pH on the growth of bacterial isolates. Growth response of different Pseudomonas species in nutritional broth grown at two different pH (5.7 and 6.80) after 24 hours of growth.

Meanwhile, population density of P. syringae declined from pH 5.70 to pH 6.80, suggesting a preference for acidic pH. P. guguanensis was highly sensitive to pH changes, as evidenced by the change in their growth response. In contrast, P. oleovorans remained constant across pH levels. The least adaptable species was P. aeruginosa, as evidenced by its slight decline in cell abundance. Similarly, P. protegens showed decreased cell growth under alkaline pH. In contrast, P.fluorescens growth response increased at higher pH values. The cell abundance value of P. viridiflava decreased markedly from pH 5.70 to pH 6.80, indicating that it prefers acidic environments. Overall, these results indicate that Pseudomonas sp.adaptations to pH are species-specific.

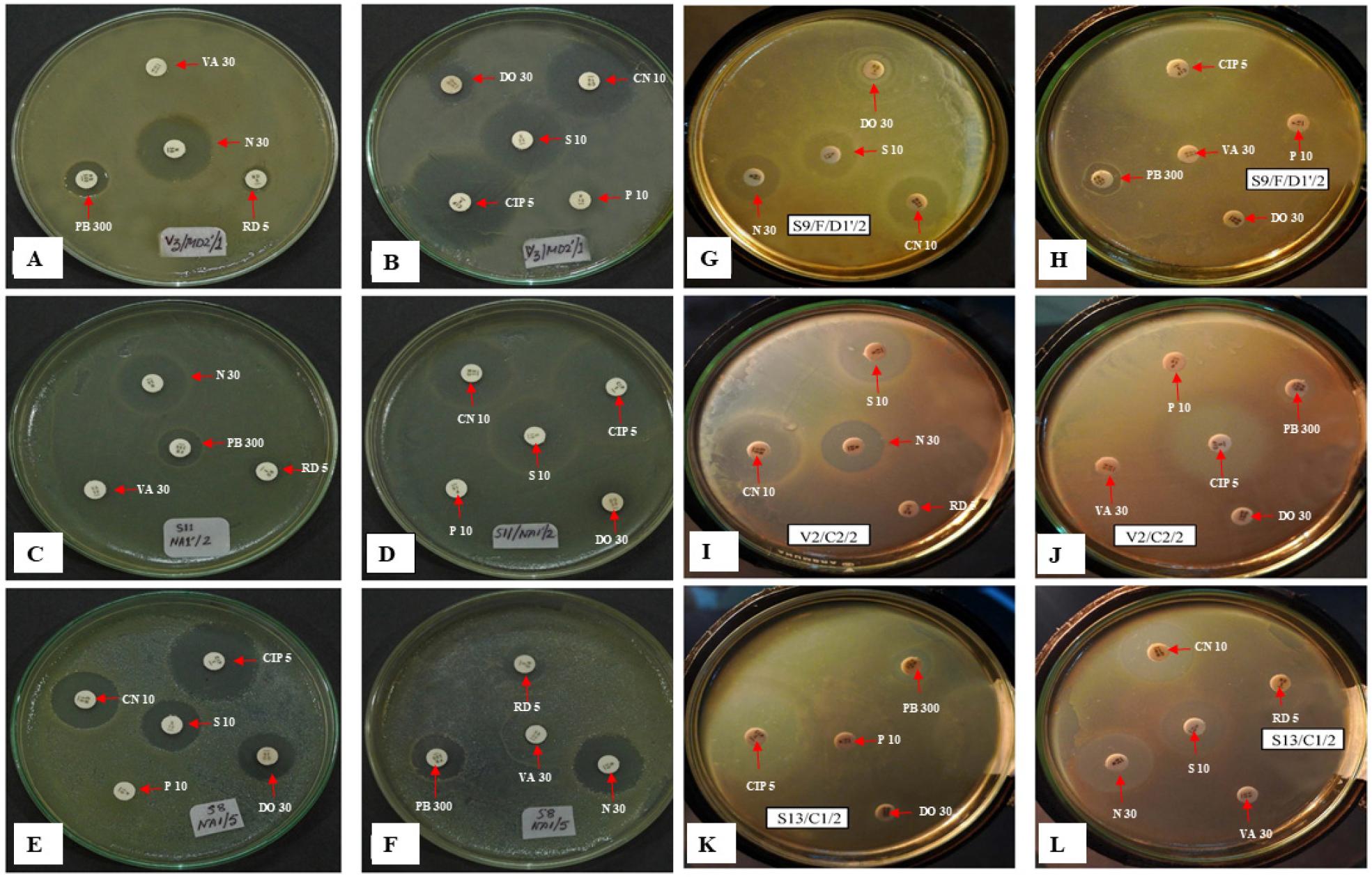

Antibiotic resistance patterns of the isolates: The results of antibiotic susceptibility tests show that all tested bacterial strains were resistant to RD, P, and VA, indicating that these antibiotics are ineffective against these strains. In contrast, all strains were susceptible to CN and S, indicating that these antibiotics are likely to be effective in controlling these strains. PB and N were also effective; however, we observed an intermediate level of resistance in P. protegens to PB and N, whereas P. aeruginosa showed an intermediate level of resistance to N. DO had varying levels of efficacy. Specifically, P. oleovorans and P. fluorescens were sensitive to DO, whereas P. syringae, P. mendocina, and P. viridiflava were resistant; P. guguanensis, P. aeruginosa, and P. protegens exhibited intermediate levels of resistance. CIP was effective against all strains except P. syringae, (Table 4).

Table 4.

Antibiotic resistance profile of the isolates

Fig. 6 shows a culture and sensitivity (C/S) test image, which provides a comprehensive view of the antibiotic susceptibility of the selected bacterial isolates. The sensitivity or resistance of Pseudomonas species to several antimicrobial agents can be inferred from the inhibition zones surrounding each strain.

Fig. 6

Photographs showing the culture and sensitivity test (C/S) of the selected isolates. Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method was used to determine the sensitivity or resistance of Pseudomonas species’ various antimicrobial compounds. Zones of inhibition were observed around tested strains (A-B) V2/SSD2´/2 = P. guguanensis, (C-D) S11/NA1´/2= P. oleovorans, (E-F) S8/NA1/5= P. fluorescens (G-H) S9/F/D1´/2= P. mendocina, (I-J) V2/C2/2= P. syringae, (K-L) S13/C1/2= P. viridiflava.

DISCUSSION

Microorganisms must adapt to environmental conditions to survive and perform essential ecosystem functions. Pseudomonas species are known to occupy different habitats where they play roles in numerous ecosystems. This study provides vital insights into microbial adaptability and highlights how these organisms adapt to various environmental conditions, in addition to their antibiotic resistance patterns.

This study revealed varying growth responses among different Pseudomonas species to changes in salinity. Most species grew slower as NaCl concentrations increased from 2% to 10%. P. fluorescens was the most salt-tolerant, as it grew well even at high NaCl concentrations. P. aeruginosa and P. protegens showed intermediate levels of salt tolerance, with low growth values at increasing salt concentrations. In contrast, the growth of P. syringae and P. viridiflava decreased considerably at high NaCl levels. P. protegens and P. oleovorans exhibited modest salt tolerance, with cell count values decreasing with increasing salt concentrations; however, these values are higher than those of the other species. P. guguanensis and P. mendocina were slightly salt-sensitive. Different Pseudomonas species have varying salt tolerance levels. For example, P. putida grows well only at NaCl concentrations of 1% to 2% (7, 22), whereas P. fluorescens grows poorly at salinities above 0.5% NaCl (23). These responses are often linked to the bacteria’s osmoregulatory adaptations, which include the synthesis of compatible solutes to mitigate osmotic stress (24). Several salt-tolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), including Pseudomonas, have been effectively used to promote plant development under salt stress (25, 26). Salt stress (1.5% NaCl) does not affect indole-3-acetic acid synthesis by root-associated PGPR strains P. putida R4 and P. chlororaphis R5, which are strains that can reduce salt stress in cotton seedlings grown in saline soil environments (26). Similarly, P. frederiksbergensis OS261 relieves salt stress under high soil salinity by reducing ethylene emission and modulating the activity of antioxidant enzymes, resulting in improved plant growth (25).

Our data show different bacterial reactions to pH variations: P. mendocina, P.guguanensis, and P. protegens decreased their activities as pH increased, whereas P. fluorescens increased its activity at higher pH values. P. syringae and P. viridiflava favored acidic conditions and exhibited decreased activity when pH increased. P. oleovorans and P. aeruginosa were essentially unaffected by changes in pH. These results show that each bacterial species has distinct pH-related adaptations that influence their growth. Generally, Pseudomonas species prefer neutral to slightly alkaline environments. For example, P. putida grows best at pH 7.0–8.0, whereas its growth is hindered at pH levels below 5.0 or above 9.0 (27). Both acidic and alkaline conditions can impact growth by affecting cell membrane integrity and protein stability (28). P. aeruginosa B0406 is classified as an opportunistic pathogen that can produce a biosurfactant that enables it to tolerate a wide range of pH (2–12) (29). Meanwhile, in P. mandelii, expression of denitrification genes (nirS and cnorB) is much lower at pH 5 than at pH 6, 7, and 8; consequently, denitrification activity is limited at low pH (27). Pseudomonas species can better utilize resources by adapting their metabolic processes to changes in acidity or alkalinity. This adaptability is crucial for their survival in various environments (30). Pseudomonas species use mechanisms such as acid shock proteins and proton pumps to tolerate pH changes (31). In P. aeruginosa, extracellular DNA (eDNA) is involved in the increased expression of 89 genes and suppression of 76 genes; many of the eDNA-induced genes are involved in DNA use and acid tolerance at pH 5 (32).

We compared the growth responses of many Pseudomonas species exposed to temperatures ranging 4°C–55°C to their corresponding responses at 37°C, which served as our baseline. Pseudomonas species generally preferred moderate temperatures near 37°C, and growth was reduced at both low (4°C and 10°C) and high (50°C and 55°C) temperatures. The results indicate that extreme temperatures are not conducive to the growth of certain Pseudomonas species and emphasize the crucial role that temperature plays in determining bacterial growth. Temperature influences bacterial growth and resistance significantly. For example, higher temperatures can increase bacterial proliferation and resistance by increasing the rates of mutation and resistance gene transfer (31). Moreover, high temperatures can also compromise water safety by decreasing disinfection effectiveness (33). Heat tolerance mechanisms such as heat shock proteins and membrane adaptations enable Pseudomonas species to tolerate a wide range of temperatures, although extreme temperatures can inhibit growth by affecting membrane fluidity or causing protein denaturation (12). Most Pseudomonas species grow best in the laboratory at 25°C–30°C. However, specific strains have varying temperature tolerances: P. aeruginosa thrives, survives, and grows at 37°C, 42°C, and 15°C, respectively, but is unable to grow below 10°C. P. putida KT2440 and P. plecoglossicida exhibit limited growth at higher temperatures, whereas P. stutzeri’s tolerance increases with its DNA’s GC content (34). P. thermotolerans sp. nov. was first isolated from the industrial cooking water and is known for its optimal and peak growth at 47°C and 55°C, respectively (35).

Our antibiotic susceptibility test results provide important insights into antibiotic efficacy against numerous Pseudomonas isolates. All tested organisms were resistant to RD, VA, and P, indicating the need for alternative treatment options. However, all tested isolates responded to CN and S. PB and N were generally effective, although P. protegens showed an intermediate level of resistance to PB, whereas P. aeruginosa and P. protegens showed intermediate levels of resistance to N. The efficacy of DO was variable. CIP was effective against all strains except P. syringae. Pseudomonas species are generally poorly susceptible to several antibiotics currently used in therapy due to the reduced permeability of their cellular envelopes and their ability to express multidrug efflux pumps and antibiotic-inactivating enzymes. Aside from their intrinsic resistance to antibiotics, Pseudomonas species can evolve antibiotic resistance through mutations (36, 37, 38). Based on the patterns of resistance we observed in Pseudomonas strains, it is important to emphasize antibiotic stewardship and develop new antimicrobial agents or strategies to combat resistant bacterial pathogens (39).

Our findings highlight Pseudomonas species’ adaptability to variations in salinity, pH, and temperature. Such adaptability has potential applications in bioprocessing, environmental science, food and beverage production, and clinical microbiology. Furthermore, we demonstrated considerable levels of antibiotic resistance among these isolates, which highlights the critical needs for better antibiotic stewardship and the development of novel strategies for the use of antimicrobials to combat MDR Pseudomonas. Additionally, our findings emphasize the necessity for personalized treatment regimens and ongoing research in efficiently managing Pseudomonas infections while preserving their roles in various ecosystems.