INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis remains a significant global health challenge, with millions of new cases reported annually despite advances in treatment strategies (1). According to the 2023 WHO report, an estimated 10.6 million people worldwide developed TB in 2022, up from 10.3 million in 2021 and 10.0 million in 2020 (2). The report also estimated that 410,000 people globally developed multidrug-resistant or rifampicin-resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB) in 2022. Approximately 3.7% of new TB cases and 20% of previously treated cases are MDR-TB, with a treatment success rate of only 54% (3). The emergence of multidrug- resistant TB strains further complicates disease management, necessitating the exploration of alternative therapeutic approaches.

Probiotics, known for their beneficial effects on host health, have recently gained attention as potential adjuncts in treating various infections, including TB (4). Probiotics play a significant role in modulating the mucosal and systemic immune systems by activating various immune mechanisms, making them effective in controlling diseases such as irritable bowel disease, allergies, diabetes, and cancer (5). Additionally, probiotics have been extensively studied for their ability to combat infectious diseases, including those caused by pathogens like Helicobacter pylori, Salmonella, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Recent research has expanded their application to antibiotic-resistant superbugs, such as Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus (VRE) (6) and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (7), as well as viral infections like HIV and SARS-CoV-2 (3). These beneficial microorganisms may exert their effects through mechanisms such as immune modulation (8), autophagy (9), competitive inhibition of pathogens (10), and production of bioactive compounds (11).

Tuberculosis primarily affects the lungs, beginning when M. tuberculosis enters the alveoli and is engulfed by alveolar macrophages, the critical site of bacterial replication (12). To assess the intracellular antimicrobial activity of probiotics against TB, we employed RAW 264.7 macrophage cell lines, an established in vitro TB model (13). Our probiotic strains exhibited efficacy against multiple TB strains at non-cytotoxic concentrations. We explored the efficacy of probiotics against M. tuberculosis, followed by comprehensive safety assessments and in vitro studies on their mechanism of inducing autophagy in macrophages.

As mentioned above, while probiotics have shown preventive and therapeutic effects against various infectious diseases, research on their impact on tuberculosis remains limited. Therefore, we aimed to identify potential anti-tuberculosis probiotic candidates. This study screened multiple probiotic strains, confirming their safety and efficacy against M. tuberculosis H37Rv in macrophage cells, and the promising results warrant future in vivo studies to develop effective biotherapeutics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microbial culture of probiotic strain

Probiotic strains were initially collected from PMC Probiotics Bank. The stocks were inoculated on BHI broth (BD Difco, USA) for enrichment in anaerobic (Baker Ruskin, Canada) and aerobic incubator (general incubator, N-Biotek, Korea) at 37°C for 24 hours. Cultures were adjusted to OD 1.0 using a spectrophotometer (Hatch, USA). Again, serial dilution was done plating on BHI agar (BD Difco, USA), and CFUs were adjusted at 1.6 × 106 CFU/mL. The pure colonies were cultured in BHI broth, and identification was performed using 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

Preparation of master cell bank (MCB) and working cell bank (WCB)

The MCB for our probiotic strains was prepared following the ICH Q5D-compliant GMP manufacture guidelines, recognizing that the quality of biological products depends on the quality of the cells used for its manufacturing (14). After the identification of the bacterial cells, MCB preparation was conducted. Before the MCB preparation, the biosafety cabinet was thoroughly cleaned and decontaminated according to the guidelines. The bacterial strains were cultured aseptically following the conditions mentioned earlier and then transferred into cryovials containing 60% glycerol, which had been autoclaved beforehand. After this, the cryovials were shaken to mix the bacterial culture and glycerol for 5 min. WCBs were subsequently prepared from the MCB under defined culture conditions. Quality control tests were performed to confirm that the MCB and the WCB are genetically identical and to ensure the WCB is free of contaminants. The prepared MCB and WBC were stored at -80°C for future uses.

Preparation of probiotic extract

The preparation of the probiotic extract involved three methods: live, bead-beating, and heat-killing. Probiotic strains were first inoculated into 30 ml of BHI broth and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours in a shaking incubator (BioFree, Korea). The cultures were subsequently adjusted to an OD600nm of 1.0. Following this, centrifugation was carried out at 4,000 g for 10 minutes using a centrifuge (Hanil Scientific, Korea), and the cells were washed with 0.85% NaCl solution to eliminate residual medium components. The pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of 0.85% NaCl solution, vortexed, and transferred to a Lysing Matrix B tube (MP Biomedicals, USA) containing 0.1 mm silica beads. Cell disruption was performed for 1 minute using a homogenizer (FastPrep-24 5G, MP Biomedicals) (4). For the heat-killing method, the resuspended pellet was subjected to heat treatment at 100°C for 10 minutes using a Thermomixer C (Eppendorf, Germany) (15).

Cell line and culture conditions

The murine macrophage RAW 264.7 cell line was obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank (KCLB, Korea). These cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, USA) with a supplementation of 10% FBS (Gibco, USA) and 1% antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin) (HyClone, USA) and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment. M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC 27294) was acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA). Using the microdilution technique, isoniazid (INH) and rifampicin (RIF) were prepared at 5 μg/ml for M. tuberculosis H37Rv. All experiments involving M. tuberculosis were performed in the Animal Biosafety Level 3 Laboratory (ABSL-3, KDCA-20-3-04).

Screening of anti-tuberculosis strain through immunofluorescence microscopy

Confocal microscopy was conducted on Raw 264.7 cells infected with M. tuberculosis H37Ra expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP), incorporating slight modifications from a previously reported method (16). GFP-expressing H37Ra was constructed by electroporating a recombinant plasmid (pFPCA1) containing the acetamidase promoter driving gfp expression (17). The procedure closely resembled the intracellular anti-mycobacterial assay described earlier, utilizing a glass-bottom 96-well plate (Cellvis, USA). Macrophages infected with GFP-labeled M. tuberculosis were incubated for 2 hours in a carbon incubator, followed by treatment with probiotic extract at 1.6 × 106 CFU/mL and incubated for 3 days. Upon incubation, 96-well plates were washed three times with 1× PBS. After treatment with 5 μM Syto59 (Invitrogen, USA) at 37°C for 30 minutes, images were captured using a confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, USA).

Intracellular anti-mycobacterial activity test using CFU assay

The intracellular anti-mycobacterial activity was assessed using the CFU assay to count the number of Tuberculosis (H37Rv) cells remaining inside macrophage cells after probiotic treatment. For this test, 96-well plates with 200 μl per well were utilized. The anti-mycobacterial effect was measured using the colony-forming unit (CFU) method. Other experimental conditions, including cell types, cell culture density, and infection parameters, remained consistent. After 3 days of incubation, the cells were lysed using distilled water (DW) based on osmotic pressure principles. Dilutions (10-fold) were plated onto 7H10 agar medium (BD Difco, USA). CFU counts of M. tuberculosis were assessed after four weeks.

Evaluation of anti-mycobacterial activity using a resazurin assay

The anti-mycobacterial activity of the candidate probiotics was evaluated using a resazurin assay (18). M. tuberculosis H37Rv strains, with an inoculum concentration of 1 × 105 CFU/ml, were prepared in a 96-well plate, treated with specified concentrations (1.6 × 106 CFU/mL) of the probiotic extract, and incubated at 37°C. After 7 days, 20 µl of freshly prepared 0.2% resazurin solution (Sigma, USA) was added to each well and further incubated for 48 hours. Fluorescence readings were then measured at 570 and 600 nm using a Victor Nivo Multiplate reader (Perkin Elmer, USA).

Cytotoxicity assay based on mitochondrial activity

Evaluating probiotic extract cytotoxicity against RAW 264.7 cells utilized the EZ-cytox cell viability assay kit solution (DoGenBio, Korea). RAW 264.7 cells (1 × 105 CFU/ml) were cultured in a 96-well plate, subjected to probiotic extract treatment at a concentration of 1.6 × 106 CFU/ml, and then incubated. Subsequently, 20 µl of Water-Soluble Tetrazolium salt (WST) solution was introduced, followed by a 2-hour incubation period. The WST assay evaluates cytotoxicity by measuring cell viability through mitochondrial reduction of WST to a formazan dye, with decreased absorbance indicating reduced viability. Cytotoxicity was assessed by measuring absorbance at 570nm using a Victor Nivo Multiplate reader.

Viable cell count using a microscope

Trypan blue and methylene blue staining methods were employed to assess the probiotic’s viability. RAW 264.7 cells were plated onto 2-well cell culture slides at 1 × 105 cells/ml and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment for 24 hours until they reached approximately 70-80% confluency. Following incubation, the cells were washed with 1× PBS and treated with probiotic extract for 3 days at 37°C with 5% CO2. After incubation, the cells were detached using a scraper and stained with trypan blue (Gibco, USA). Viable cell counts were then performed using a hemocytometer (Marienfeld, Germany) and observed under an optical microscope (AX10, Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Hemolytic activity of probiotic strains

Fresh probiotic cultures were evaluated for hemolytic activity on blood agar, allowing the identification and selection of isolates demonstrating gamma hemolysis. Bacterial inoculum was streaked onto agar media containing 5–10% sheep blood (Kisan Bio, Korea) and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. The isolates were inspected for the presence of distinct zones surrounding the colonies. Beta hemolysis was identified by clear zones, alpha hemolysis by greenish zones, and the absence of zones, indicating no hemolysis, was classified as gamma hemolysis (19).

Assessment of D-lactate production

The D-lactate assay determined excessive D-lactate production, which may lead to D-lactic acidosis, a significant safety concern (20). The production of D-lactate by the candidate probiotic strains was assessed after incubation at 37°C for 24 hours in MRS and BSM broth culture. The culture supernatants were collected, and D-lactate concentrations were measured using the D-lactate assay kit (Abcam, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. A standard D-lactate solution was prepared as a reference, and measurements were conducted using a Victor Nivo microplate reader. Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus KCTC5033 was a negative control (NC) for D-lactate production.

Bile salt deconjugation test

The bile salt deconjugation activity of the strains was evaluated using Taurodeoxycholic acid sodium salt (TDCA, Millipore, Germany) using a plate assay technique (21). TDCA-MRS agar (BD Difco, USA) plates were prepared using 1 mm sodium salts per liter. Probiotics were streaked onto TDCA-containing agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 5 days. Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus KCTC5033 and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum KCTC3105 (KCTC, Korea) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively, for bile salt deconjugation.

E-test for antimicrobial susceptibility

The antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial strains was assessed using the E-test method (22). Strains were inoculated on agar plates specific to their growth requirements, as mentioned previously, along with E-test strips (Liofilchem, Italy), followed by incubation in aerobic conditions at 37°C for 48 hours. After incubation, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values were determined by reading the point at which the inhibition ellipse intersected the E-test strip scale. The MIC values were then compared to the EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) MIC cut-off criteria (23) to determine susceptibility or resistance profiles.

Real-time PCR for autophagy gene expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from probiotic-treated RAW 264.7 cells with a kit of RNA protection bacteria reagent (Qiagen, Germany) described by the manufacturer’s protocol to observe the autophagy gene expression. Next, the total RNA integrity was checked by agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified by a Qubit Fluorometer (Invitrogen, USA) using a Qubit RNA Assay kit (Thermo fisher, USA). RNA samples were then reverse transcribed to cDNA with a kit of cDNA synthesis (Bio-Rad, USA), and Real-time PCR was carried out using the SYBR Green Supermix Kit (Bio-rad, USA) with a CFX96 Real-Time PCR detection system following the instructions provided by the company (Applied Biosystems, USA). The values of target gene expression were standardized for the endogenous control gene, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), using the comparative Ct method described previously (24).

Quantification of nitric oxide reduction

The concentration of nitrite (NO₂⁻), serving as an indicator for nitric oxide (NO) production, was determined using the Griess reagent as previously described (25). In brief, RAW 264.7 cells were seeded into 96-well cell culture plates at a density of 1 × 10⁵ cells/ml per well and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. The cells were then infected with M. tuberculosis and washed three times with 1× PBS. Following the washes, the cells were treated with probiotic extract and incubated for 3 days. For NO quantification, 50 μl of the cell culture supernatant was collected and mixed with 50 μl of Griess reagent solution (G2930, Promega, USA) in a new 96-well plate, then incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. A standard curve was generated according to the manufacturer’s protocol to determine nitrite levels accurately. Finally, absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a Victor Nivo microplate reader.

RESULTS

MCB and WCB stock preparation

In this study, 20 MCBs were prepared for each candidate probiotic strain. Before preparation, 16S rRNA sequencing was conducted for each strain to confirm purity (Table 1). Subsequently, 50 WCB was prepared for each strain from the previously prepared MCB (Supplementary Fig. 1). The prepared WCB was then used for the anti-tuberculosis assay and safety assessment. While preparing the WCB from MCB, the viability and integrity of the WCB were evaluated.

Table 1.

Results of 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis for anti-tuberculosis candidate strains

| Strains | NCBI Ref. | Organism | Length | Score | Identities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. crispatus | NR_119274.1 | Lactobacillus crispatus strain DSM 20584 | 1491 | 2750 bits (1489) | 1490/1491 (99%) |

| NR_041800.1 | Lactobacillus crispatus strain ATCC 33820 | 1518 | 2745 bits (1486) | 1486/1486 (100%) | |

| NR_117063.1 | Lactobacillus crispatus strain DSM 20584 | 1516 | 2723 bits (1474) | 1474/1474 (100%) | |

| P. acidilactici | NR_042057.1 | Pediococcus acidilactici DSM 20284 | 1569 | 2739 bits (1483) | 1500/1508 (99%) |

| NR_042058.1 | Pediococcus pentosaceus strain DSM 20336 | 1569 | 2634 bits (1426) | 1481/1508 (98%) | |

| NR_041640.1 | Pediococcus acidilactici NGRI 0510Q | 1540 | 2586 bits (1400) | 1456/1480 (98%) | |

| L. rhamnosus | NR_113332.1 | Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus strain NBRC 3425 | 1495 | 2654 bits (1437) | 1440/1441 (99%) |

| NR_043408.1 | Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus strain JCM 1136 | 1521 | 2641 bits (1430) | 1437/1441 (99%) | |

| NR_037122.1 | Lacticaseibacillus zeae strain RIA 482 | 1522 | 2579 bits (1396) | 1426/1441 (99%) | |

| B. sonorensis | NR_113993.1 | Bacillus sonorensis strain NBRC 101234 | 1475 | 2700 bits (1462) | 1469/1472 (99%) |

| NR_157609.1 | Bacillus haynesii strain NRRL B-41327 | 1508 | 2684 bits (1453) | 1468/1475 (99%) | |

| NR_118996.1 | Bacillus licheniformis strain DSM 13 | 1545 | 2678 bits (1450) | 1467/1475 (99%) | |

| B. subtilis | NR_027552.1 | Bacillus subtilis strain DSM 10 | 1517 | 2706 bits (1465) | 1465/1465 (100%) |

| NR_112116.2 | Bacillus subtilis strain IAM 12118 | 1550 | 2700 bits (1462) | 1464/1465 (99%) | |

| NR_180419.1 | Bacillus cabrialesii strain TE3 | 1550 | 2700 bits (1462) | 1464/1465 (99%) | |

| B. velezensis | NR_075005.2 | Bacillus velezensis strain FZB42 | 1550 | 2708 bits (1466) | 1472/1475 (99%) |

| NR_041455.1 | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain NBRC | 1472 | 2697 bits (1460) | 1468/1472 (99%) | |

| NR_112685.1 | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain NBRC 15535 | 1475 | 2693 bits (1458) | 1467/1472 (99%) | |

| B. bifidum | NR_118793.1 | Bifidobacterium bifidum strain KCTC 3202 | 1488 | 2669 bits (1445) | 1454/1458 (99%) |

| NR_113873.1 | Bifidobacterium bifidum strain NBRC 100015 | 1453 | 2639 bits (1429) | 1444/1451 (99%) | |

| NR_117764.1 | Bifidobacterium bifidum ATCC 29521 | 1344 | 2449 bits (1326) | 1339/1345 (99%) |

Screening of anti-tuberculosis strain through immunofluorescence microscopy

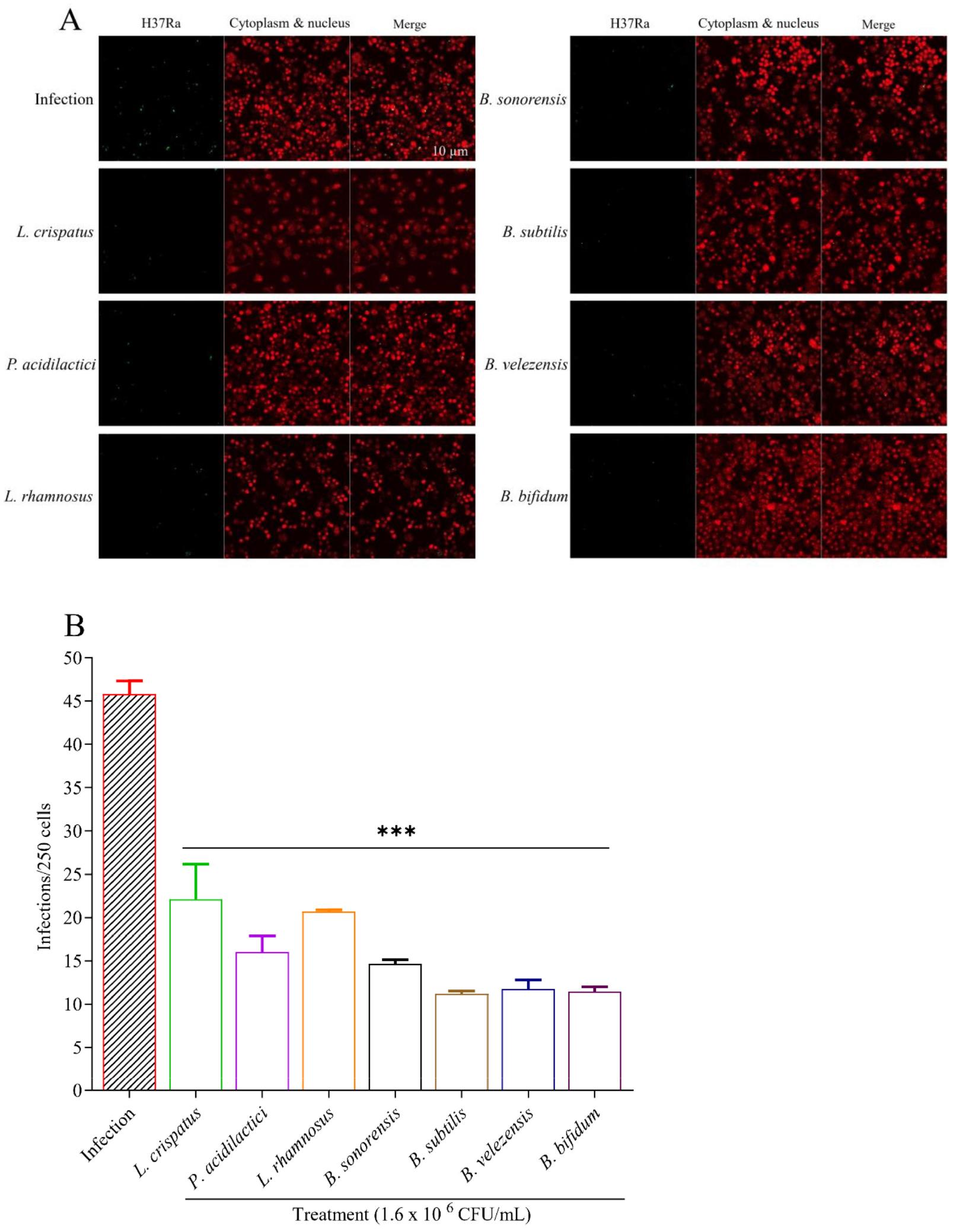

Confocal microscopy assessed the intracellular anti-mycobacterial activity of a probiotic extract in Raw 264.7 cells infected with GFP-expressing M. tuberculosis H37Ra. The resulting images provided a clear visualization of the intracellular localization of M. tuberculosis. They allowed for assessing the probiotic extract’s anti-mycobacterial activity (Fig. 1A). All 7 candidate strains significantly reduced TB burden inside Raw 264.7 cells, while B. subtilis, B. velezensis, and B. bifidum (p <0.001) showed multiple-fold reduction when the images were analyzed, manually counting the number of GFP-expressing cells and represented the data using a graph (Fig. 1B). For this total number of GFP-TB was counted and expressed as the number of TB per 250 cells through visual inspection, counted and calculated accordingly. Confocal microscopy enables precise visualization of intracellular M. tuberculosis, essential for evaluating the efficacy of probiotic extracts in reducing the bacterial burden within host macrophage cells, a crucial step in anti-tuberculosis therapy development.

Fig. 1

Effect of probiotics extracts on GFP-expressing M. tuberculosis H37Ra infected macrophages. A) Cells were first infected with TB and then treated with candidate probiotic strains. After observing with a confocal microscope, it is visible that the number of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) TB is less in probiotic-treated groups compared to infection, indicating that probiotic extract successfully killed or eliminated TB. The green signal indicates M. tuberculosis H37Ra, and the red signal indicates Raw 264.7 cells. B) The total TB per 250 macrophage cells was counted and compared to the non-treated group.

Intracellular anti-tuberculosis activity of candidate probiotics

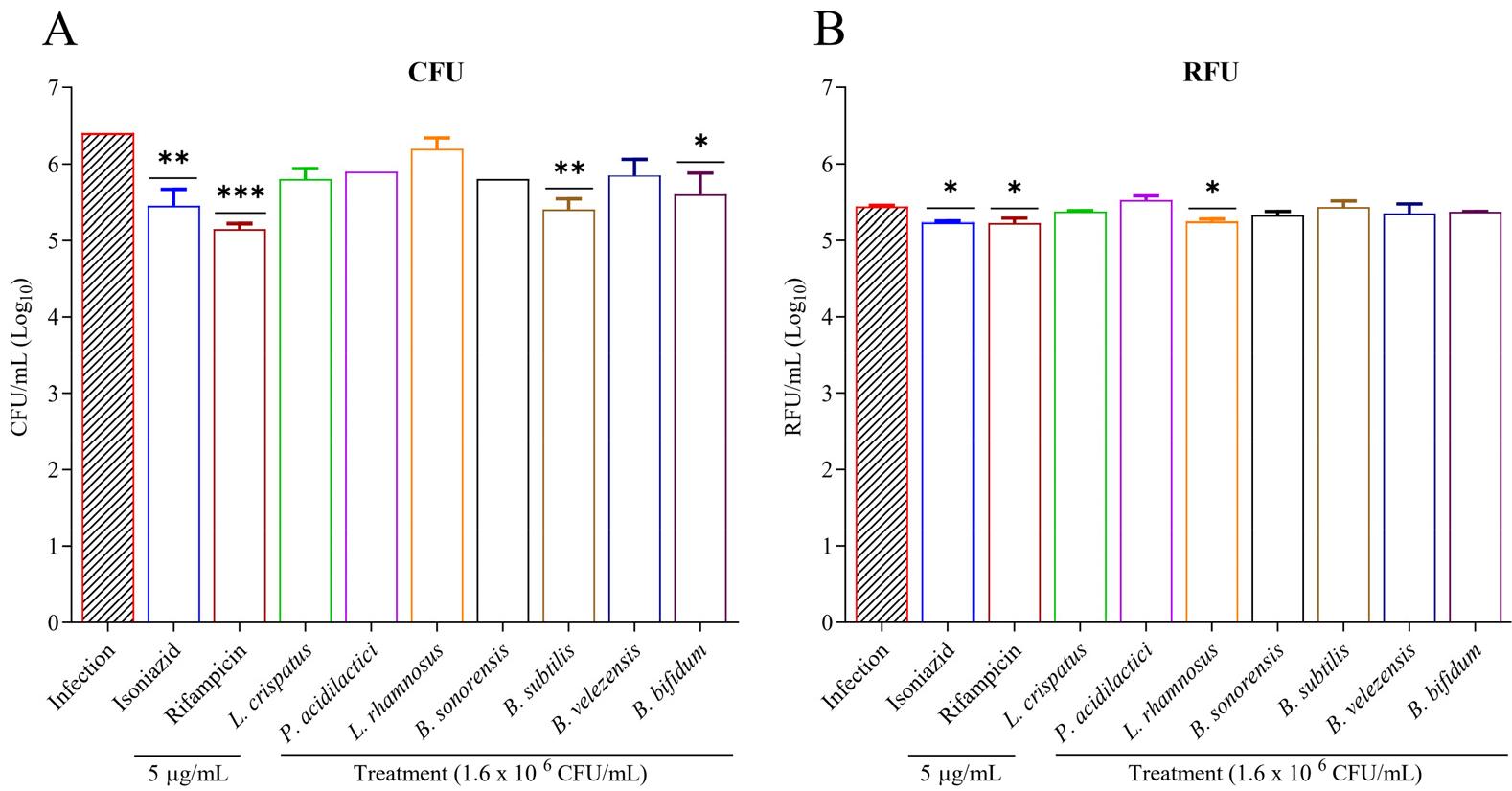

Anti-mycobacterial activities of candidate strains against M. tuberculosis strains were assessed with CFU and resazurin assay. The assay result showed the significant growth inhibition of M. tuberculosis H37Rv treated with B. subtilis (p <0.01) and B. bifidum (p <0.05) (Fig. 2A). The reference drugs also demonstrated significant efficacy against H37Rv at lower concentrations, ranging from 5 µg/ml. These findings indicate that candidate probiotic extract has anti-tuberculosis activities against M. tuberculosis strains. A similar result of M. tuberculosis reduction was also observed in the resazurin assay (Fig. 2B). Here, all the strains except P. acidilactici showed a reduction of TB burden while treating with L. rhamnosus (p <0.05) reduced TB burden significantly. These assays are critical for quantifying the inhibitory effects of probiotic strains on M. tuberculosis growth, confirming their potential as anti-TB agents by showing significant bacterial burden reduction, akin to reference drugs used in TB treatment.

Fig. 2

Assessment of intracellular elimination of probiotic bacteria within macrophage cells. A) RAW 264.7 cells were infected with M. tuberculosis H37Rv, treated with a drug and probiotics for 3 days, and then TB was extracted and cultured on 7H10 media. CFU were counted after a 4-week incubation. B) The inhibitory effect of probiotic extract against M. tuberculosis H37Rv strain was evaluated. Mycobacterial susceptibility was checked by resazurin assay as RFU/ml (relative fluorescence unit per ml. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and *Statistical significance with controls was determined using Graph Pad Prism 9.1.1, one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Cytotoxicity of candidate strains

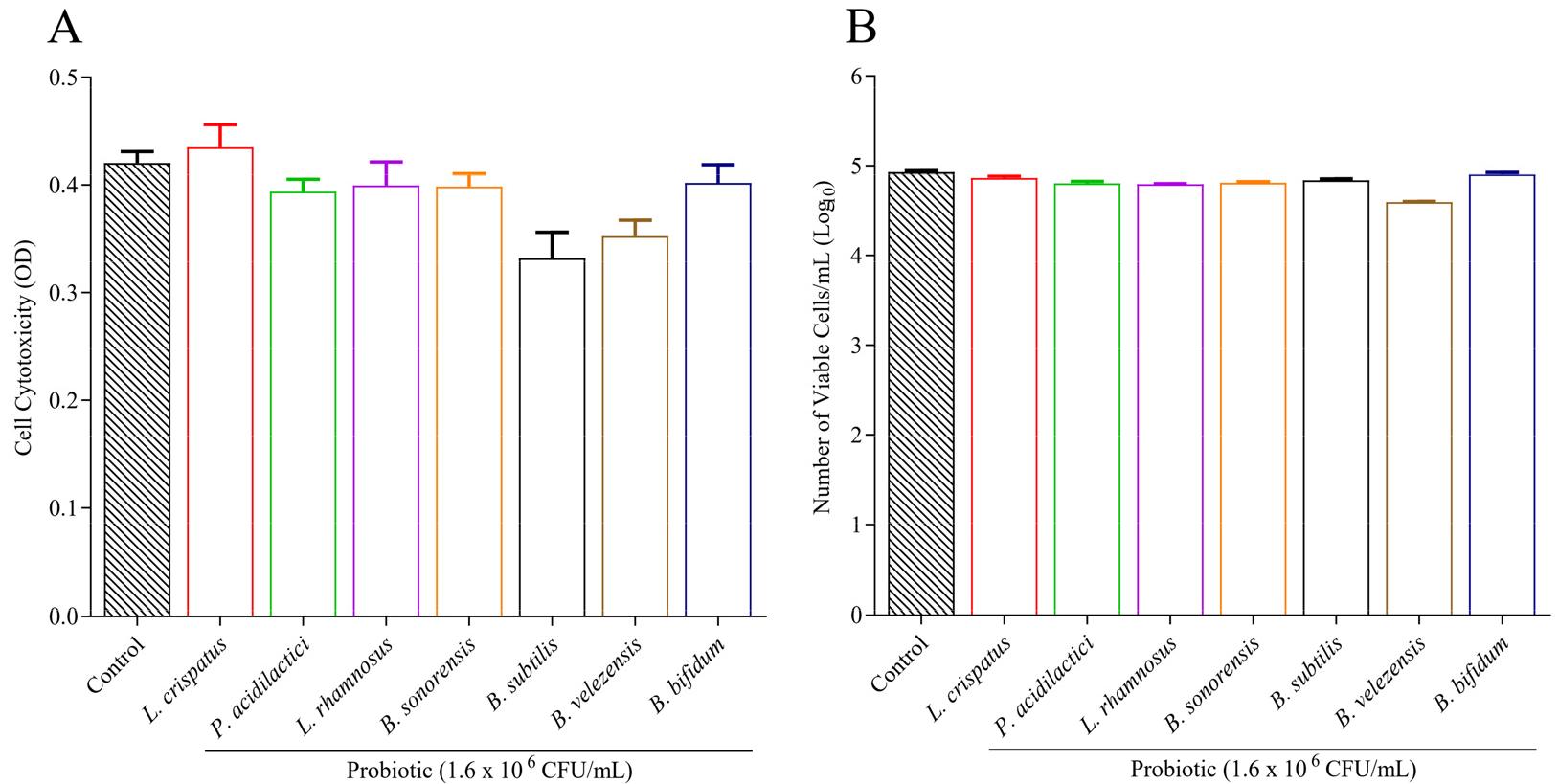

Cytotoxicity was the primary step in determining the candidate strain’s cytotoxic effect on RAW 264.7 cells. The cytotoxicity of candidate strains measured using EZ-cytox reagent is shown in figure (Fig. 3A). The result showed that 5 out of 7 candidate strains have less or no cytotoxic effect on macrophage cell lines. Cell viability was also assessed using a trypan blue staining test, where treated cells were examined under an optical microscope (Fig. 3B). No noticeable decrease in viability or morphological changes were observed compared to the control sample at similar concentrations of probiotic extract used in the Ez-cytox cell viability assay.

Fig. 3

Cytotoxicity and cell count of RAW 264.7 cells upon probiotic treatment. A) Several strains were subjected to a cytotoxicity test using an EZ-cytox reagent kit. Cytotoxicity was measured through a microplate reader and expressed by Optical Density. Probiotic strains were compared with the control, which is RAW cell only, with a lower OD value meaning a higher cytotoxicity. B) Cell viability was calculated using a microscope after treating macrophage cells with probiotic extract. RAW 264.7 cells were cultured in a flask and treated with candidate probiotic strains for 72 hours. Trypan blue was used for staining. Only live cells were counted and compared with the control, and values were expressed in a Logarithmic scale. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Hemolytic activity of probiotic strains

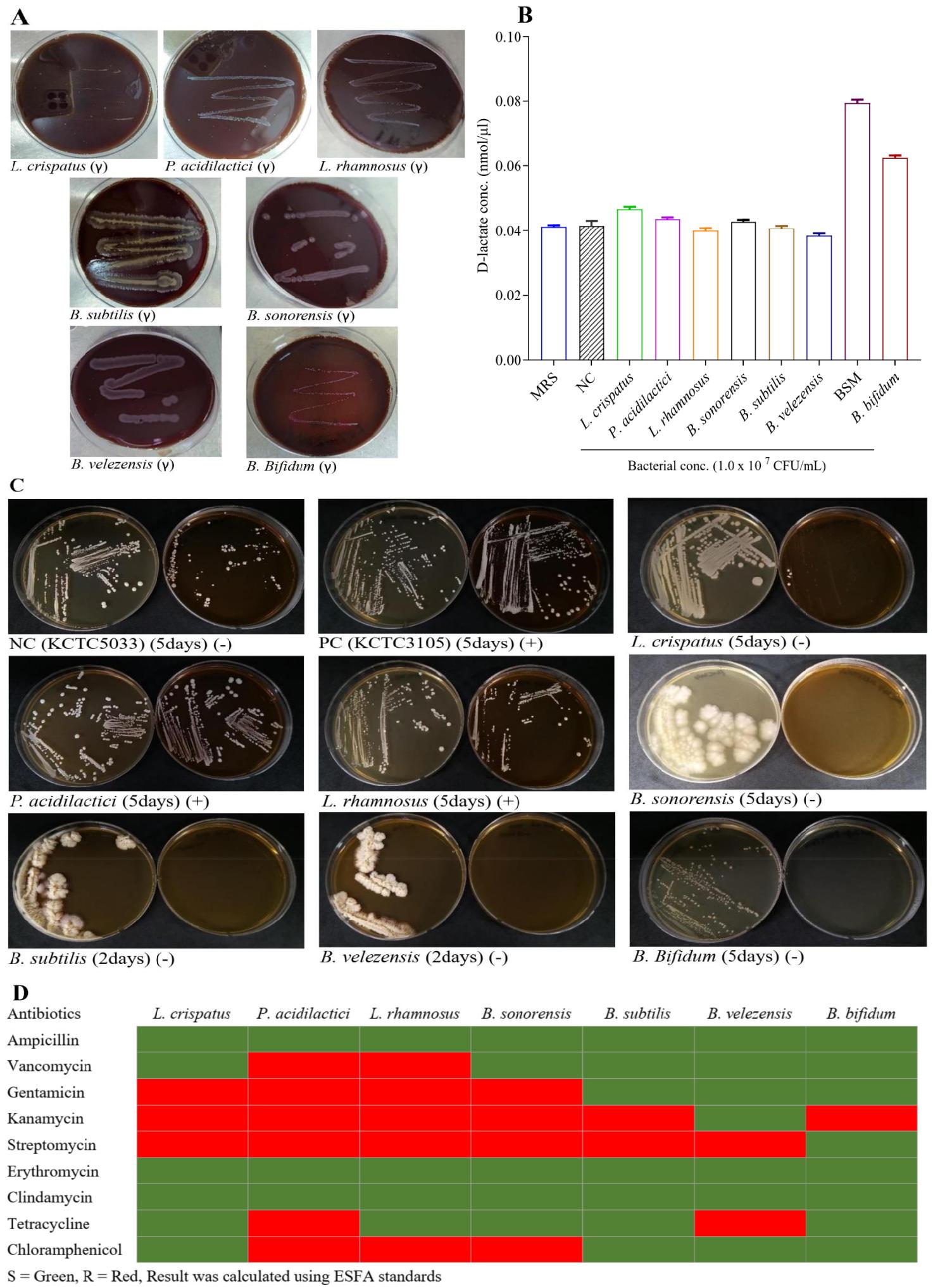

The hemolytic activity of the seven probiotic strains was evaluated using blood agar plates. Hemolysis was assessed by observing the presence or absence of clear (β-hemolysis), greenish (α-hemolysis), or no (γ-hemolysis) zones around the bacterial colonies after incubation. None of the tested probiotic strains exhibited hemolytic activity. All strains demonstrated γ-hemolysis, as evidenced by the absence of clear or greenish zones around the colonies on the blood agar plates (Fig. 4A). This indicates that the probiotic strains did not lyse red blood cells under the conditions tested, confirming their non-hemolytic nature.

Fig. 4

Safety Evaluation of Probiotic Strains. To confirm whether the probiotic strains are safe for therapeutic application, hemolytic activity, D-lactic acid measurement, bile salt hydrolase activity, and antibiotic susceptibility testing were evaluated. A) All strains exhibited γ-hemolysis (no hemolysis) on blood agar plates, demonstrating non-hemolytic characteristics. B) D-lactate production of seven probiotic strains measured in mmol/µL, with L. crispatus and P. acidilactici exhibiting detectable levels. C) Bile salt deconjugation test showing the growth of seven probiotic strains along with positive and negative control on plates with and without TDCA. L. rhamnosus and B. sonorensis exhibit bile salt tolerance. D) Heatmap showing antibiotic sensitivity (green) and resistance (red) of seven probiotic strains against nine antibiotics.

Assessment of D-lactate production

The D-lactate production results are presented in Fig. 4B, with concentrations measured in mmol/µL. Among the tested probiotic strains, L. crispatus and P. acidilactici exhibited measurable D-lactate levels, while the other strains showed little to no D-lactate production. These findings are significant, as excessive D-lactate production can lead to D-lactic acidosis, which raises safety concerns in probiotic applications. The low or absent D-lactate levels in most strains suggest their suitability for probiotic use, ensuring minimal risk of inducing D-lactic acidosis in clinical settings. This is crucial for the safety profile during drug development.

Bile salt deconjugation test

The bile salt deconjugation activity of the tested strains is shown in Fig. 4C. Among the strains, L. rhamnosus and B. sonorensis demonstrated positive bile salt deconjugation, while others showed no deconjugation activity. The ability to deconjugate bile salts is an essential characteristic of probiotics, as it enhances their survival in the gastrointestinal tract by facilitating bile salt tolerance, a critical factor in maintaining viability and functionality in the harsh intestinal environment.

Antibiotic susceptibility of probiotics

The antibiotic susceptibility profiles of candidate probiotic strains are summarized in Fig. 4D. All tested strains exhibited sensitivity to ampicillin, erythromycin, and clindamycin. At the same time, vancomycin resistance was observed in P. acidilactici and L. rhamnosus. Gentamicin and kanamycin resistance was common, particularly in all strains except B. subtilis and B. velezensis, which showed sensitivity to gentamicin and partial sensitivity to kanamycin. Resistance to streptomycin was widespread, with only B. bifidum being sensitive. Notably, tetracycline resistance was limited to P. acidilactici and B. velezensis. The distribution of MICs confirms the strains’ antibiotic resistance patterns in line with EFSA standards, underlining the importance of e-tests in evaluating probiotic safety for drug development by ensuring probiotic strains do not harbor or transfer resistance genes, a critical concern for clinical applications.

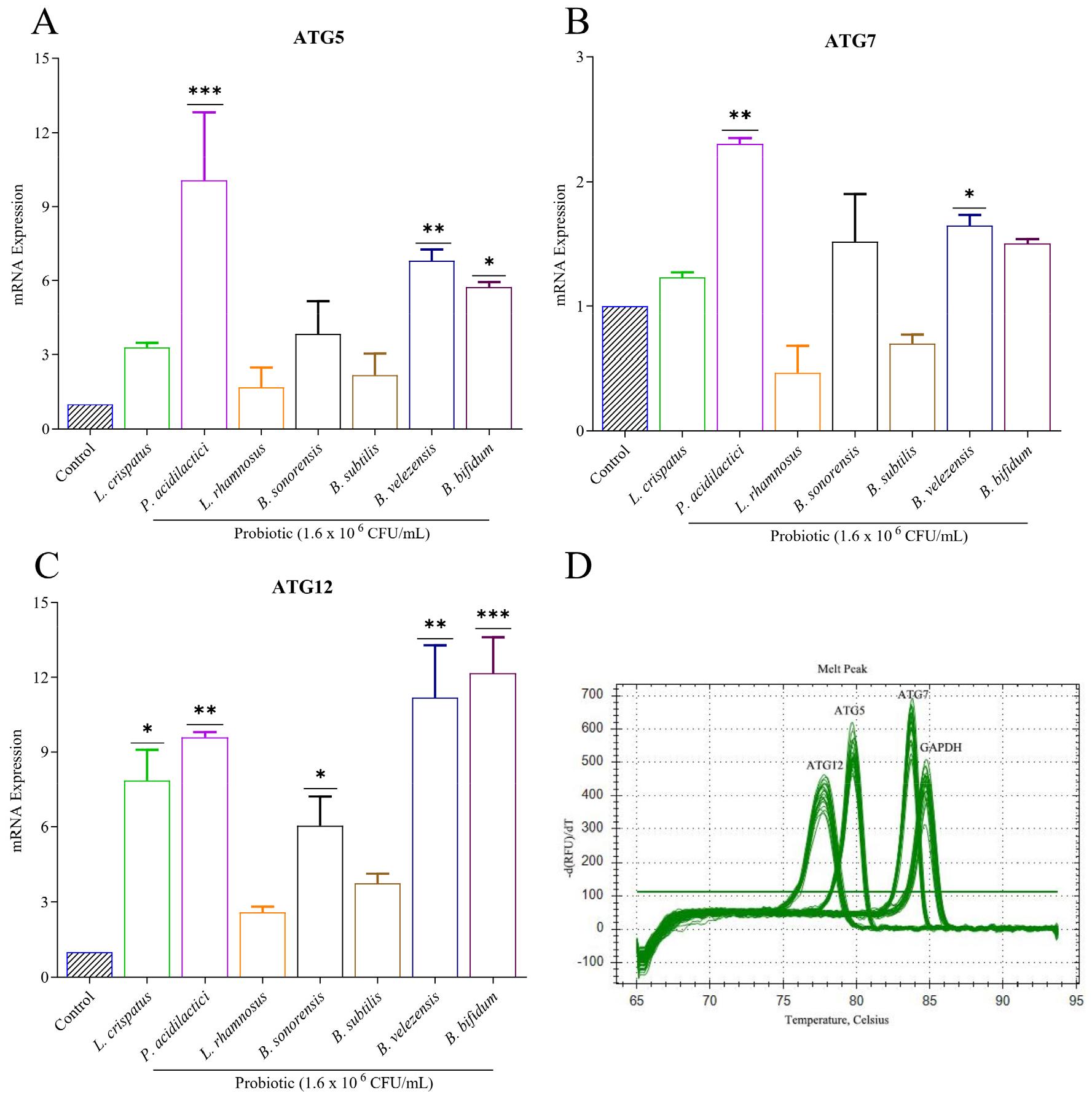

Upregulation of autophagy-related genes

The mRNA expression levels of genes involved in autophagy induction and lysosomal biogenesis were assessed (Fig. 5). The results indicated a significant upregulation in the expression levels of autophagy-related genes following treatment with the candidate probiotic strains compared to the control group. Notably, genes such as ATG3, ATG7, and ATG12 exhibited a marked increase in expression, ranging from 2- 9 fold, after treatment with P. acidilactici, B. velezensis, and B. bifidum. Although other strains also showed increased gene expression, these changes were not statistically significant. The upregulation of autophagy-related genes such as ATG3, ATG7, and ATG12 after probiotic treatment highlights the role of autophagy in enhancing the host’s ability to combat TB, suggesting that probiotic strains can stimulate intracellular defense mechanisms critical for tuberculosis clearance.

Fig. 5

Autophagy gene expression detection in M. tuberculosis-infected macrophage cells. A-C) Raw 264.7 cell lines were treated with the cell extract of probiotics. mRNA expressions of ATG5, ATG7, and ATG12 genes were checked, and quantitative RT-PCR detected the autophagy gene complex. These experiments were performed in triplicate. Values were calculated and determined using the 2-∆∆Ct method. D) PCR amplification curve of autophagy genes along with control. *Statistical significance with controls was determined using Graph Pad Prism 9.1.1, one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

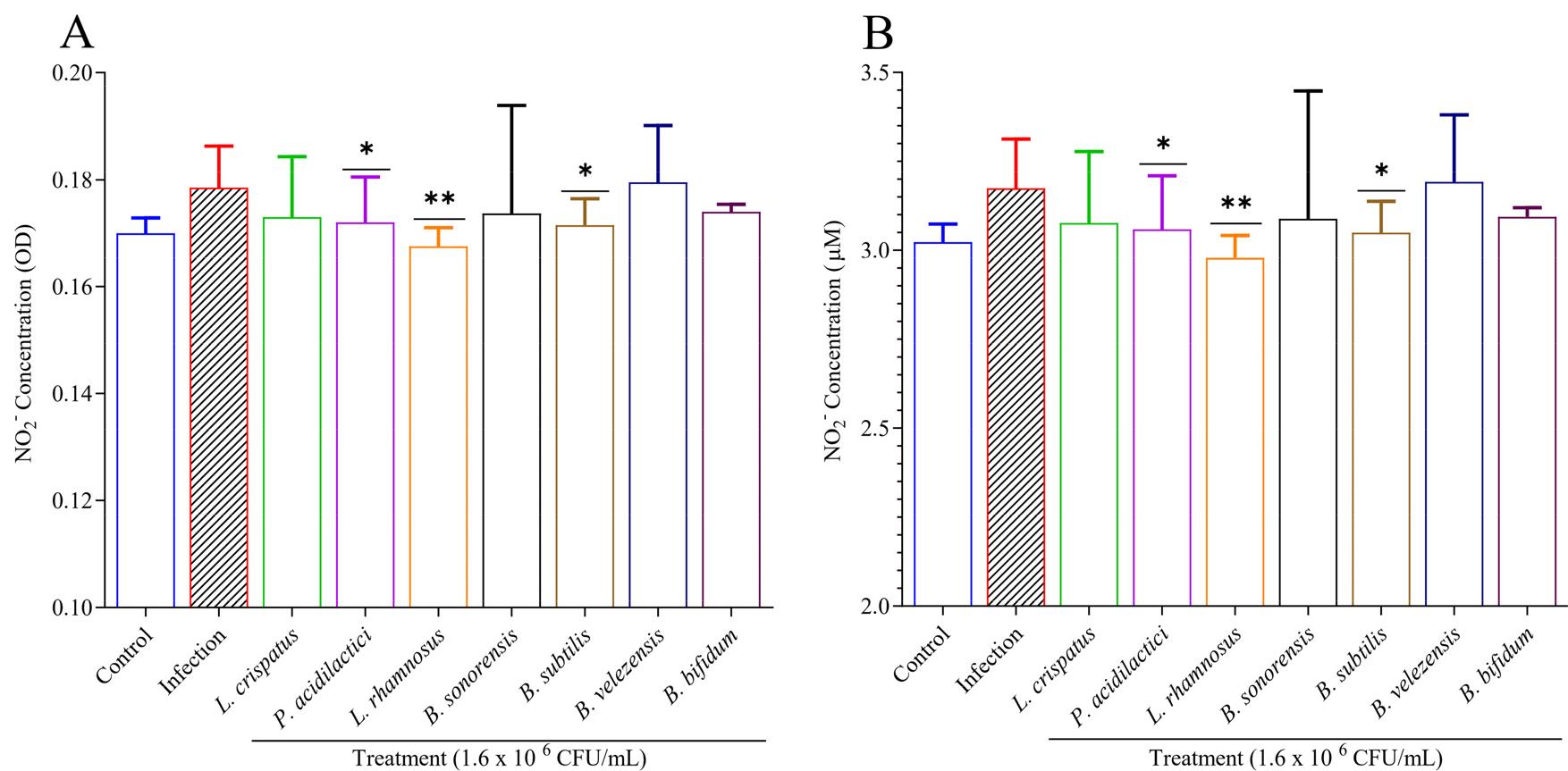

Evaluation of the effect of probiotics on nitrite production

The effect of candidate strains on nitrite production was tested (Fig. 6). Macrophage cells were infected with M. tuberculosis H37Rv and treated with 7 candidate strains for 3 days. Nitrite levels, serving as an indicator of NO₂⁻, were then quantified using the Griess reagent. Nitrite production in RAW 264.7 cells was induced 3 days after infection with M. tuberculosis H37Rv, resulting in an increased nitrite level of up to 3.17 µM. After the treatment of the candidate probiotic, the level of nitrite was significantly reduced for P. acidilactici (p <0.05), L. rhamnosus (p <0.01), and B. subtilis (p <0.05). Monitoring nitrite levels provides insight into the inflammatory response during TB infection, and the significant reduction in nitrite production following probiotic treatment suggests an anti-inflammatory effect, which is crucial for mitigating excessive immune responses and aiding in tuberculosis control.

Fig. 6

Effects of probiotics on nitrites (NO2-) in M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages. A-B) After infecting RAW 264.7 cells with M. tuberculosis H37Rv, probiotic extract at a concentration of 1.6 × 106 CFU/mL was used for treatment for 3 days. A Griess reagent quantified nitrite as a nitric oxide (NO) indicator. Results were expressed in both A) OD value B) and µM concentration, where data showed that after the probiotic treatment, nitrite concentration significantly reduced compared to infection. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Statistical significance with controls was determined using Graph Pad Prism 9.1.1, one-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infects one-fourth of the global population and is among the most formidable bacteria causing infectious diseases (26). Its ability to evade host defense mechanisms and withstand most antimicrobial agents—due to the accumulation of resistance mutations leading to multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR), and more recently, totally drug-resistant (TDR) strains—poses a significant challenge in the field of healthcare and medicine (27). Various strategies are being explored to address this issue, including repurposing existing drugs for combination therapy (28), developing new compounds with novel mechanisms of action, and employing host-directed therapies to modulate the immune response (29). In this context, probiotics are emerging as a promising alternative for TB treatment (30). They have recently been recognized for their potential in controlling tuberculosis by stimulating host immunoglobulins and producing antibacterial compounds (31). Our study investigated the anti-tuberculosis effect of the probiotic strains from the PMC probiotics bank and explored its mechanisms for the intracellular killing of M. tuberculosis.

The primary site of tuberculosis infection is the lungs, with pulmonary disease present in over 80% of TB cases (32). Infection begins when the bacterium, delivered in a water droplet to an alveolus, is ingested by an alveolar macrophage (33). To investigate the intracellular killing effect of our candidate probiotic strain, we utilized RAW 264.7 macrophage cell lines, a well-established in vitro model in TB research (34). We employed dozens of probiotics for screening against M. tuberculosis, and we found 7 of them were more efficient based on confocal microscopy using GFP-TB. We selected a concentration of 1.6 × 106 CFU/mL as it was the highest concentration observed to have optimal anti-TB efficacy without causing in vitro toxicity. We employed probiotic lysate in-vitro inside macrophage cells, the primary infection site for TB in the human body. We employed immunofluorescence microscopy using GFP-labelled M. tuberculosis H37Ra, which allowed for clear visualization of bacteria (green fluorescence) and macrophage cells (red fluorescence stained with Syto59) (35). While this method effectively showed the interaction between the pathogen and host cells, it did not distinguish between viable and non-viable bacteria. We also conducted a CFU assay to quantify viable bacteria to overcome this limitation, providing a complementary perspective. Our combined approach revealed that certain probiotic strains significantly reduced M. tuberculosis burden by directly killing the bacteria as indicated by CFU reduction or other mechanisms that reduced bacterial fluorescence without a corresponding drop in CFU counts. Moreover, the resazurin method also explored the anti-tuberculosis effect based on mitochondrial reductase activity (36). Some strains exhibited a reduction in the TB burden as indicated by both CFU and RFU measurements, resulting in similar trends, albeit not identical. The differences arise from the distinct mechanisms underlying these two experimental methods. CFU quantifies the viable bacterial load, directly measuring M. tuberculosis growth. At the same time, RFU reflects the fluorescence emitted by M. tuberculosis cells, which can be influenced by factors such as cellular uptake and retention of the bacteria. These findings suggest that probiotic extracts could serve as a complementary strategy against tuberculosis, with future research needed to uncover the specific mechanisms involved.

While most probiotic strains are classified as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS), their safety evaluation remains paramount due to direct human consumption. The Joint FAO/WHO Working Group established standardized safety criteria in 2002 (37), subsequently adopted by the Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (KMFDS) in 2021 (38). Probiotic strains must undergo rigorous testing, including antibiotic resistance assessment per EFSA guidelines (39), hemolytic activity evaluation, cell cytotoxicity, and metabolic characterization. After exploring the anti-tuberculosis effect of candidate strains, we focused on cytotoxic effects and safety. Bacteria have both adverse and beneficial effects on host cells, especially in macrophage cells (40). As we aim to develop biotherapeutics against tuberculosis, it is urgent to determine the level of cytotoxicity. The WST assay measures cytotoxicity by assessing cell viability based on mitochondrial activity (41). Living cells reduce the WST salt to a soluble formazan dye, which can be quantified by measuring its absorbance. A decrease in absorbance indicates reduced cell viability, reflecting cytotoxic effects (42). By the way, EZ-cytox has some limitations, as it is a turbidimetric assay, so it is more of a qualitative than a quantitative assay. Cell viability was assessed by staining RAW cells with trypan blue and observing them under a microscope to differentiate viable from non-viable cells (43). In this assay, dead cells retain the blue color from trypan blue and become blue, while live cells remain white. Though most strains are non-cytotoxic in an optimal dose by overall cytotoxicity test, some have mild cytotoxic effects, which we will consider carefully in future experiments. We performed antibiotic susceptibility testing following EFSA and KMFDS guidelines, using a range of antibiotics commonly used to treat infectious diseases. Most strains that showed susceptibility to these antibiotics are considered safer for further development as they are unlikely to interfere with TB treatment or harbor resistance genes. It is important to note that some probiotics naturally resist specific antibiotics, such as Lactobacillus species being inherently resistant to vancomycin (44), which explains why certain probiotic strains may show resistance. We also assessed hemolytic activity, which is a crucial factor in evaluating the safety of probiotic strains. We have also checked the hemolytic activity of candidate strains. Hemolytic strains can cause harm to the host. Understanding hemolytic potential helps ensure safety and provides insights into host interactions, RBC, and cell wall properties (45). Another essential safety assessment is bile salt deconjugation, an essential function of many probiotic strains. While deconjugating bile salts help probiotics survive and colonize the gut, excessive deconjugation may disrupt normal bile metabolism and lead to gastrointestinal issues, including diarrhea or impaired fat absorption (46, 47). Additionally, we measured the production of D-lactate by the candidate strains, as D-lactate accumulation can be harmful, particularly in individuals with impaired metabolism. Excessive D-lactate can lead to D-lactic acidosis, a condition characterized by symptoms such as confusion and ataxia, especially in people with short bowel syndrome or other gastrointestinal disorders (48). Our candidate strains demonstrated no or low levels of D-lactate production, indicating a reduced risk of inducing D-lactic acidosis.

Autophagy is a complex cellular process in which cytoplasmic components are engulfed by double-membrane autophagosomes and delivered to lysosomes for degradation (26). This process is crucial in immune defense against pathogenic bacteria like M. tuberculosis(27). This study explored whether our isolated probiotic strains are involved in inducing autophagy. We assessed the mRNA expression of autophagy-related gene families (ATG), which are integral to the autophagy machinery and essential for LC3 attachment to the autophagosome membrane (28). The differences in the expression levels of the three ATG genes could be due to the differential regulation of autophagy at various pathway stages. Post-transcriptional regulation or feedback mechanisms may also contribute to the variations in expression. Our findings indicate that 3 probiotic strains activate autophagy through the ATG gene complex, thereby reducing the M. tuberculosis burden in macrophage cell lines, consistent with previously published research. It has been shown that some strains have an anti-tuberculosis effect, but their autophagy gene expression is not that significant, which means they have another anti-mycobacterial mechanism.

Probiotics can modulate the innate and acquired immune systems by affecting mucosal and systemic immune responses, making them useful in immunotherapy (49). This has increased interest in their potential role in tuberculosis treatment (50). The inhibitory effect of probiotic strains on M. tuberculosis in macrophages may be linked to its ability to regulate immune responses. To explore this, we examined its association with nitric oxide (NO), a key player in the immune system (51). Our analysis revealed that our isolated probiotics reduced NO levels, which had been elevated by M. tuberculosis infection. This reduction could be related to the cytoprotective effects previously observed with probiotics (52). While probiotics are believed to influence immune responses by activating various inflammatory cytokines and interleukins associated with tuberculosis, further research is needed to understand these mechanisms fully (50).

Our study demonstrates that the candidate probiotic strains, particularly B. subtilis, B. velezensis, and B. bifidum, exhibit significant intracellular anti-mycobacterial activity against M. tuberculosis in RAW 264.7 cells, as evidenced by confocal microscopy and CFU assays. Interestingly, P. acidilactici, while showing less direct bacterial reduction, significantly upregulated autophagy-related genes (ATG3, ATG7, and ATG12) and reduced nitrite production, suggesting an immunomodulatory role through enhanced autophagy and anti-inflammatory effects. Meanwhile, B. subtilis also significantly reduced nitrite in RAW cells. These findings highlight the diverse mechanisms through which different probiotic strains may contribute to tuberculosis control, either through direct bacterial killing or by modulating host immune responses. This dual action suggests that probiotics serve as valuable adjuncts in TB therapy by simultaneously reducing bacterial load and mitigating excessive immune responses.

In summary, this study showed the effects of multiple probiotic strains on M. tuberculosis in vitro and suggested that it could be used as a candidate anti-tuberculosis agent for treating TB. This suggests they can be used as biotherapeutic agents and in combination therapy. However, more extensive studies are needed, including evaluation of the in vivo animal efficacy, clinical trials, and its mechanism of action.

CONCLUSION

This research identifies promising probiotic strains with anti-tuberculosis activity, offering potential alternatives to conventional treatments amidst rising drug-resistant TB strains. The findings support further investigation into these probiotics as biotherapeutic in TB therapy. Further research is needed to elucidate mechanisms of action and evaluate clinical potential.