INTRODUCTION

Salmonella, a causative agent of salmonellosis in several hosts, belongs to the family Enterobacteriaceae, class Gammaproteobacteria (γ-proteobacteria), and phylum Pseudomonadota (Proteobacteria), and is a gram-negative, flagellated, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped bacterium (1, 2). Salmonella species are primarily classified as follows: enterica and bongori (Table 1) (3). S. enterica comprises more than 2,600 serovars and is taxonomically classified into six subspecies. Moreover, DNA homology studies have revealed that S. enterica is the most clinically significant isolate (4, 5). The six phylogenetic groups of S. enterica include S. enterica subspecies enterica (I), salamae (II), arizonae (IIIa), diarizonae (IIIb), houtenae (IV), and indica (VI) (6, 7, 8, 9, 10). Among these six subspecies, the subspecies enterica is pathogenic and contains approximately 1,580 serovars, which have adverse health effects on homeotherms (11). The other subspecies are economically relevant in poikilotherms, and their pathogenicity is limited (12).

Table 1.

Salmonella species, subspecies, number of serovars, and common habitats. There are two major species of Salmonella, enterica and bongori, and over than 2,600 serovars, according to the Kauffman-White classification (12)

| Species | Subspecies | Number of serovars | Common habitats | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. enterica | enterica | 1,586 | Homeotherms, environments | (6) |

| salamae | 522 | Poikilotherms, environments | (7) | |

| arizonae | 102 | Poikilotherms, environments | (8) | |

| diarizonae | 338 | Poikilotherms, environments | (9) | |

| houtenae | 76 | Poikilotherms, environments | (10) | |

| indica | 13 | Poikilotherms, environments | (6) | |

| S. bongori | - | 22 | Poikilotherms, environments | (3) |

Salmonellosis, one of the most common foodborne diseases, impacts the health of several hosts, including animals, birds, fish, and humans, through the consumption of contaminated water and food. Based on its surface antigen composition, Salmonella subspecies I is divided into typhoidal and non-typhoidal Salmonella (13). Typhoidal Salmonella spp. (S. enterica subspecies enterica serovars Typhi and Paratyphi) have adapted to their human hosts, wherein they cause systemic infections known as typhoid and paratyphoid fever, respectively. These species are highly adapted to humans and do not cause diseases in non-human hosts (14, 15, 16, 17). Non-typhoidal Salmonella have a broad host range and most often cause gastroenteritis in humans (18). Host immunity plays a central role in shaping the course of diseases caused by non-typhoidal Salmonella(19).

Salmonella can colonize nearly all animals, including poultry, reptiles, rodents, domestic animals, birds, and humans. Animal-to-animal spread and use of Salmonella-contaminated feed maintain animal reservoirs. The most common sources of human infections include poultry, eggs, dairy products, and foods prepared on contaminated work surfaces (20). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Salmonella is responsible for approximately 1.35 million infections, 26,500 hospitalizations, and 420 deaths annually in the United States, resulting in an estimated $400 million of direct medical costs (21). Furthermore, the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) reported an average of 2,315.78 cases of Salmonella infections over the past decade (22). Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) updated its priority list of bacterial pathogens, identifying certain critical priority pathogens that continue to pose a major global threat. Seven years since its publication, Salmonella (S. Typhi and non-typhoidal Salmonella) has been included in the updated list as a high-priority pathogen owing to its particularly high burden in low- and middle-income countries and increasing levels of resistance (23). Despite extensive studies on Salmonella pathogenicity and infection mechanisms, salmonellosis outbreaks continue to occur worldwide, posing a threat to public health.

This review focuses on non-typhoidal Salmonella and elaborates on the causes of its infection, pathogenic mechanisms, and salmonellosis, which is the most frequent foodborne disease in humans. In addition, strategies have been described for the prevention and control of Salmonella to enhance human safety and public health.

NON-TYPHOIDAL SALMONELLA INFECTION AND PATHOGENIC MECHANISMS

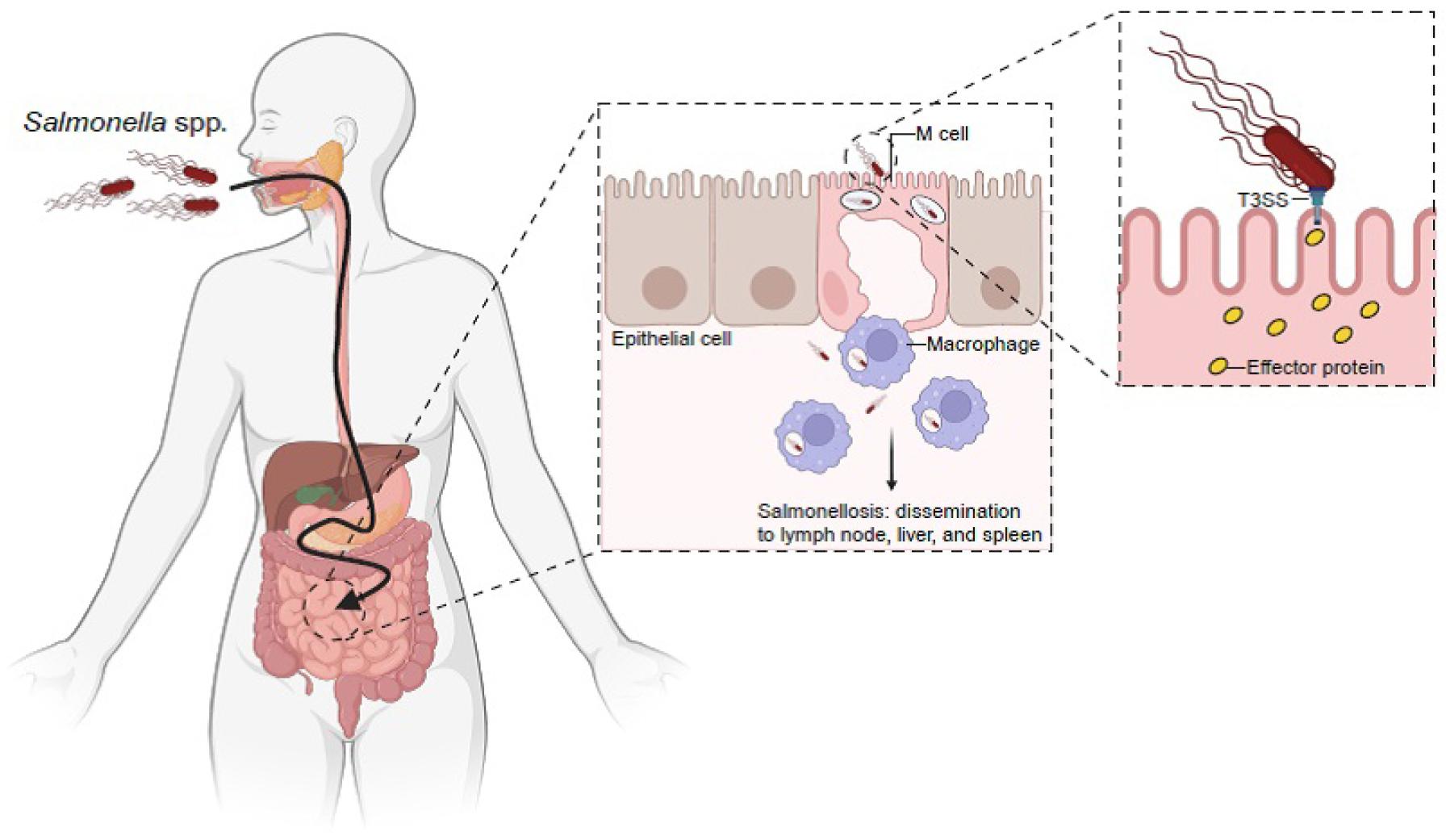

Non-typhoidal Salmonella, such as S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) is most often acquired through the consumption of contaminated food and water (17, 24, 25). However, exposure to reptiles and amphibians, which often carry bacteria, poses a risk of salmonellosis in humans. After ingestion and passage through the stomach, Salmonella attach to the mucosa of the small intestine and invade microfold (M) cells located in Peyer’s patches and enterocytes (Fig. 1) (26, 27). The bacteria remain in endocytic vacuoles, called Salmonella-containing vacuoles (SCV), wherein they replicate. Bacteria can also be transported across the cytoplasm and released into blood or lymphatic circulation (28, 29). The presence of multiple mechanisms for crossing the cellular barrier indicates the importance of this strategy in Salmonella lifecycle.

Fig. 1

Salmonella spp. mechanism of infection. Orally ingested Salmonella spp. survive at a low pH in the stomach and evade multiple defenses of the small intestine to gain epithelial access. Salmonella spp. preferentially enter M cells in the underlying Peyer’s patches. Salmonella spp. deliver effector proteins to host cells via the type III secretion system (T3SS). T3SS is encoded by Salmonella spp. within its pathogenicity island-1 (SPI-1). Effector proteins delivered by this system trigger host cell responses that result in bacterial internalization and the formation of Salmonella-containing vacuoles (SCV). Salmonella spp. induce an early local inflammatory response and salmonellosis (Created by BioRender).

Although non-typhoidal and typhoidal Salmonella share a high degree of homology, with their genomes being approximately 89% identical and having similar pathogenic mechanisms, there are a number of differences between them (30, 31). Typhoidal Salmonella harbors unique virulence factors, which are absent in non-typhoidal Salmonella(30, 31). For example, SPI-7 encodes genes for the synthesis and export of Vi capsular polysaccharide (ViCPS) (32, 33, 34), which masks lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and flagellin in S. Typhi, thereby preventing the host’s innate immune response (33, 35). Moreover, typhoidal Salmonella possesses a typhoid toxin, which is crucial for its pathogenesis and is absent in non-typhoidal Salmonella(36, 37). Some non-typhoidal Salmonella strains have typhoid toxin homologs with 1% amino acid variation, resulting in minimal systemic toxicity but preferential binding to glycan receptors on small intestinal epithelial cells (38). This corresponds to the observation that non-typhoidal Salmonella primarily localizes to the small intestine in healthy individuals, whereas typhoidal Salmonella disseminates systemically.

Pathogenicity islands (PAIs) are genetic islands related to pathogenicity, acquired by pathogenic bacteria via horizontal gene transfer. PAIs do not occur in non-pathogenic bacteria, indicating their importance in bacterial pathogenicity (39). PAIs in Salmonella spp. are called Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPIs), and contain several genes related to Salmonella pathogenicity. To date, 17 SPIs have been identified (39). SPI-1 is a crucial factor responsible for the interactions between the host and Salmonella spp. SPI-1 is responsible for the formation of the needle-shaped type III secretion system (T3SS), which facilitates the translocation of virulence factors into host cells (Fig. 1) (40). SPI-2 also synthesizes T3SS for the translocation of effector proteins; however, the genes encoding T3SS differ from those encoding the T3SS of SPI-1 (28). SPI-3 is a 17 kb locus that contains the mgtCB operon (magnesium transport system, important for survival in nutrient starved states) and MisL, which functions as an adhesin (39, 41, 42). SPI-4 encodes genes required for the type I secretion system (T1SS) and non-fimbrial adhesin SiiE, which are involved in epithelial cell binding (43). SPI-5 is approximately 7.6 kb and encodes the effector proteins SPI-1 and -2 (44). SPI-6, also known as the Salmonella centisome 7 genomic island (SCI), contains the fimbriae-encoding gene saf and invasion protein gene pagN(45). SPI-7 is a large genetic island (134 kb) that carries genes for virulence factors, such as the Vi antigen, sopB, and type IVB pili (46). SPI-8 has been identified in S. Typhi, and encodes virulence factors with unknown functions (39). SPI-9 is involved in the adherence of S. Typhi but not in biofilm formation (47). SPI-10 is a hypervariable locus inserted into the leuX tRNA gene that encodes genes related to fimbrial adhesion, such as sef and pef(48). SPI-11 and -12 were detected in S. Choleraesuis. They exhibit the characteristics of bacteriophage genomes and tRNA genes; however, their exact functions remain unknown (49). SPI-13 is in close proximity to pheV tRNA, whereas SPI-14 is not. Both SPIs are present in S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis, but not in S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi (50). SPI-15, -16, and -17 are present in S. Typhi and associated with tRNA genes. Additionally, SPI-16 and -17 are also associated with LPS modulation (51).

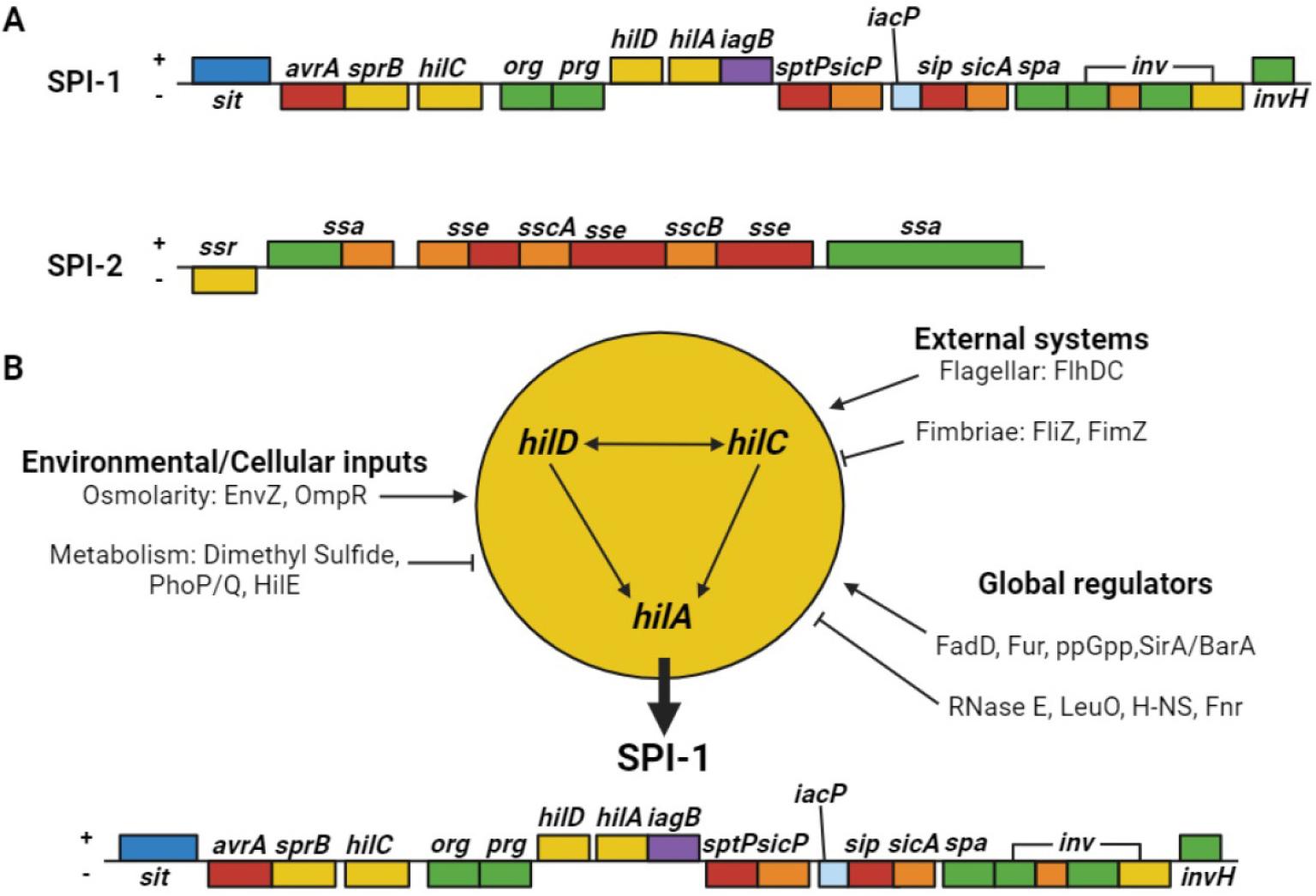

Among the various SPI loci, SPI-1 and -2 have been extensively studied (Fig. 2) (17, 25, 40, 52). SPI-1 encompasses several operons including inv-spa, sicA-sip, prg, and org(40, 53, 54). SPI-1 also encodes T3SS, an invasion island in all Salmonella species and subspecies, with genes for invading non-phagocytic cells. Contact with intestinal epithelial cells activate T3SS, thereby delivering several effector proteins, which have the capacity to modulate various host processes (55, 56). The injected effector proteins induce cytoskeletal rearrangement, which allows the internalization of Salmonella on the epithelial cell membranes into the cellular mucosa (57). During internalization, Salmonella enters the vacuolar compartment known as SCV. The bacterium blocks the fusion of SCV with a terminal acidic lysosome, which constitutes an important intracellular defense strategy for the host cell (58). Upon sensing the phagosomal environment, SPI-2, which encodes T3SS, enables the bacterium to survive in phagocytic cells and replicate within the SCV in host cells (59, 60). Inside phagocytic cells (that is, macrophages), SCV matures, ruptures, and disseminates Salmonella into reticuloendothelial cytosol (liver and spleen) through the blood or lymphatic circulation and induces a systemic phase of infection (61). Other SPIs are primarily involved in host cell survival, replication, and production of proteins, adhesins, toxins, and fimbriae (39, 62, 63). All these effects could contribute to intestinal Salmonella colonization or intracellular growth. However, typhoidal and non-typhoidal Salmonella share T3SS, but there are differences in their pathogenesis. The role of SPI-2 in typhoidal Salmonella remains unclear, although some effectors are crucial for competitive growth in human macrophages (64, 65). Typhoidal Salmonella has a reduced functional effector repertoire, wherein approximately half of the Salmonella T3SS effectors are either pseudogenes or missing (31). The absence of the protease effector GtgE in S. Typhi, which facilitates S. Typhimurium growth in mouse macrophages by cleaving the host cell Rab32, contributes to host restriction (66). Furthermore, the SPI-1 effector SptP, essential for host cytoskeleton recovery post-infection in S. Typhimurium, is nonfunctional in S. Typhi due to variations in the SicP binding domain that impair SptP-SicP binding and hinder its translocation and activity (67, 68).

Fig. 2

Salmonella pathogenicity islands-1 and -2 (SPI-1 and -2) and associated factors. (A) Schematic illustrations of SPI-1 and -2. Each colored box represents an operon based on protein function. Blue, iron transport protein; red, T3SS secreted protein; yellow, transcriptional regulator; green, secretion apparatus; purple, cell invasion protein; orange, chaperone; light blue, likely acyl carrier protein. (B) Multiple SPI-1 gene regulators. 1) Environmental/cellular inputs: the osmolarity-related proteins EnvZ and OmpR positively regulate SPI-1, whereas metabolic inputs, such as dimethyl sulfide, PhoP/Q, and HilE, negatively regulate SPI-1. 2) External systems: FlhDC positively regulates SPI-1, whereas the fimbriae proteins FliZ and FimZ negatively regulate SPI-1 expression. 3) Global regulators: the positive regulators include FadD, Fur, ppGpp, and SirA/BarA, whereas the negative regulators include RNase E, LeuO, H-NS, and Fur.

In summary, the acquisition of broad virulence factors and functional effectors observed in non-typhoidal Salmonella appear to be consistent with its lifestyle and broad host range.

CLINICAL DISEASES CAUSED BY NON-TYPHOIDAL SALMONELLA

Globally, non-typhoidal Salmonella affects approximately 93.8 million people and causes 160,000 fatalities annually (69, 70). The primary route of Salmonella infection in humans is through the consumption of contaminated foods, including beef, pork, chicken, eggs, milk, fruits, vegetables, and water, or fecal–oral transmission (71). Gastroenteritis, septicemia, enteric fever, and asymptomatic colonization are mainly caused by Salmonella.

Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis is the most common form of salmonellosis worldwide (72). The onset of symptoms typically occurs 6–48 h after consuming contaminated food or water. Initially, affected individuals experienced nausea, vomiting, and non-bloody diarrhea. Fever, abdominal cramps, myalgia, and headaches are also common symptoms. Colonic involvement is observed in acute forms of the disease. Symptoms typically persist for up to 2–7 days before clearing up on their own (73).

Septicemia

All Salmonella species can cause bacteremia, although infection with typhoidal Salmonella commonly leads to a bacteremia phase. However, approximately 5% of individuals with gastrointestinal illnesses caused by non-typhoidal Salmonella develop bacteremia (18). The risk of Salmonella bacteremia is high in pediatric and geriatric patients, and immunocompromised patients (for example, those with HIV infections, sickle cell disease, and congenital immunodeficiencies) (18, 74, 75). The clinical presentation of Salmonella bacteremia is similar to that of other gram-negative bacteria; however, localized suppurative infections (for example, osteomyelitis, endocarditis, and arthritis) can occur in up to 10% of patients (76).

Enteric fever

S. Typhi causes a febrile illness known as typhoid fever. The intermediate form of this disease, referred to as paratyphoid fever, is caused by S. Paratyphi (77). Non-typhoidal Salmonella rarely cause similar symptoms (78). The bacteria responsible for enteric fever pass through the cells lining the intestine and are engulfed by macrophages (79). They replicate after translocating to the liver, spleen, and bone marrow (61). Up to 10–14 days after ingesting food or water contaminated by bacteria, patients experience a gradually increasing fever with non-specific complaints of headaches, myalgia, malaise, and anorexia. These symptoms typically persist for one week or longer and are followed by gastrointestinal symptoms. This cycle corresponds to an initial bacteremia phase, followed by gallbladder colonization, and intestine reinfection (77, 79). Enteric fever is a serious clinical disease that should be considered in febrile patients who have recently traveled to developing countries, where the disease is endemic (80).

Asymptomatic colonization

Salmonella spp. responsible for causing typhoid and paratyphoid fever are maintained through human colonization (81). Chronic colonization for more than one year after symptomatic disease develop in 3–5% of patients, with the gallbladder being the reservoir in most patients. Chronic colonization by other Salmonella spp. that cause gastroenteritis occurs in ≤ 1% of patients and does not represent an important source of human infections (82).

MULTIDRUG-RESISTANT NON-TYPHOIDAL SALMONELLA

In the 1980s, non-typhoidal Salmonella spp. were drug-sensitive. However, in the 1990s, the clinical isolates investigated at CDC exhibit increased resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ) (18). Many countries have used various antibiotics to treat salmonellosis, leading to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella.

Antibiotic resistance is a global concern in Salmonella spp. infections (83). In addition, it has continuously increased, exhibiting an escalating trend of 20–30% per decade. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) non-typhoidal Salmonella spp. can cause life-threatening diseases that cannot be treated with common antibiotics. Notably, MDR serotypes with high prevalence frequently tend to develop resistance against commonly prescribed antibiotics (83). MDR Salmonella spp. have also been identified in several studies. For example, MDR Salmonella was detected in 17% of broiler chickens in Egypt, with the highest resistance against neomycin (100%), nalidixic acid, cefoxitin (95%), and chloramphenicol (40.9%) (84). In 2014, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and a segment of the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) collected chicken breast samples during routine monitoring. The samples were tested using whole-genome sequencing (WGS), and MDR S. Infantis was identified, with the highest resistance observed against aminoglycosides, chloramphenicol, β-lactams, and tetracyclines. This strain includes a combination of 6–10 resistance genes (blaCTX-M-65, aac(3)-IVa, aadA1, aph(4)-Ia, aph(3′)-Ia, floR, sul1, dfrA14, tetA, and fosA) that are not common among Salmonella isolates from chickens in the United States (85). Furthermore, in the Salmonella isolates collected from 2015 to 2017, 18% of the samples were MDR Salmonella, resistant against ciprofloxacin, azithromycin, ceftriaxone, ampicillin, and TMP-SMZ (Table 2) (21, 86). Moreover, MDR Salmonella strains are also resistant to colistin, carbapenem, and tigecycline (87).

Table 2.

Drug-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella. Some non-typhoidal Salmonella spp. become less susceptible to essential antibiotics, thereby jeopardizing the treatment of severe infections (86)

| Percentage of all non-typhoidal Salmonella* | Estimated number of infections per year | Estimated infections per 100,000 U.S. population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceftriaxone resistance | 3% | 41,000 | 10 |

| Ciprofloxacin non-susceptible | 7% | 89,200 | 30 |

| Decreased susceptibility to azithromycin | 0.5% | 7,400 | ≤ 5 |

| Resistant to at least one essential antibiotic† | 16% | 212,500 | 70 |

| Resistant to three or more essential antibiotics† | 2% | 20,800 | 10 |

Taken together, new therapeutic strategies, such as targeting resistance mechanisms, are required to combat MDR Salmonella development. Sequential antibiotic therapy and antibiotic rotation, both of which reduce side effects, have gained increasing attention in recent years. Chloramphenicol has typically been used to treat Salmonella infections. However, the preferred antibiotics include ampicillin, third-generation quinolones such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, and third-generation cephalosporins such as ceftriaxone and macrolides (88). However, these approaches may favor cross-resistance to different antibiotics (89). Cross-resistance evaluation of different strains of Salmonella under sequential antibiotic treatment showed that effective therapeutic strategies, appropriate selection, and antibiotic therapy can help in the prevention of MDR Salmonella infections (87). Therefore, tracking the origin and development of MDR Salmonella via the implementation of nationwide monitoring systems through extensive genomic studies is crucial.

PREVENTION AND CONTROL OF NON-TYPHOIDAL SALMONELLA INFECTIONS

Several strategies are required for the prevention and control of non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in humans. Among the various strategies, the following can be considered for the prevention and control of non-typhoidal Salmonella infections.

Biosecurity measures

Biosecurity measures, including the identification of the source and transmission route (90, 91), isolation of ill animals, access control, and stringent sanitation (92, 93), prevent non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in farms. External measures include boundary fencing, vehicle regulation, and controlled animal introduction (94, 95), whereas internal measures include changing clothing and shoes, quarantining symptomatic animals, and frequent cleaning (96). High-risk visitors and uninformed farmers pose considerable risk (97, 98). Risk reduction guidelines involve limiting visitor access (99), providing clean clothing and footwear (100), removing debris, using disinfectant footbaths (101), prioritizing healthy and young animals (102), using separate or sanitized tools for food and waste, avoiding tool sharing, and restricting and sanitizing vehicles (98, 103).

Vector control and eradication

Insects, rodents, and wild birds act as vectors to facilitate the spread and persistence of non-typhoidal Salmonella infections, necessitating regular disinfection and rodent control to prevent transmission to livestock (104). Maintaining high sanitation levels is key to deterring rodents and managing insect carriers (105). Regular use of synthetic insecticides and organophosphates is recommended, although they are highly toxic and require careful application (93, 106). Natural alternatives, such as essential oils and bioinsecticides are effective, eco-friendly, and economical (107).

Isolation and quarantine

Isolation and quarantine measures effectively prevent non-typhoidal Salmonella infections and environmental contamination (108). Quarantine prevents the transmission of infection to healthy humans and protects vulnerable individuals in hospitals. Isolation units require separation from healthy areas and the proper disposal of manure (109). Quarantine duration varies based on pathogen type and exposure status (110), matching the pathogen’s incubation period for healthy exposed individuals and relying on symptoms and laboratory confirmation for infected humans (111). These measures could safeguard human health.

Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point principles and food safety

The globally acknowledged Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) system, aligned with the ISO 22000 standards and its updated protocols, enhances food safety management by preventing pathogenic contamination. However, foodborne illnesses still exist owing to inadequate cleaning, awareness, resources, and training (112). The system assesses contamination in food chains to mitigate physical, chemical, and microbiological risks, which are crucial amid evolving pathogens, antimicrobial resistance, and environmental changes. By identifying critical control points (CCPs), HACCP is essential for managing food safety and quality (113) and benefiting stakeholders across various food sectors (114).

Animal feeds

Salmonella spp., transmitted via contaminated feed ingredients (115), include serovars S. Typhimurium, S. Montevideo, S. Hadar, and S. Tennessee (116). Ensuring animal product safety can be done by reducing Salmonella contamination by heat treatment, organic acids, and chemical preservatives (117, 118, 119). Prebiotic herbs and spices, added as dried plants, extracts, or parts, enhance animal health and performance by modulating intestinal microflora, preventing Salmonella adhesion, and promoting Lactobacillus growth (120). Their antimicrobial actions disrupt microbial cell membranes, increase leakage, and diminish the proton motive force, thereby promoting appetite, digestion, physiological health, and animal productivity (121).

Epidemiological surveillance

WGS-based Salmonella surveillance identifies and manages outbreaks that are crucial for controlling human infections from contaminated food or water (122). From 1990 to 1995, S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium were prevalent in Europe and the Americas, mainly from poultry, while S. Typhi predominated in Africa due to poor sanitation (123). Studies linked S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis to poultry, and detected S. Anatum and S. Weltevreden in beef and seafood, highlighting the role of surveillance in guiding interventions and reducing the risk of salmonellosis (124). Analyzing outbreak data facilitates the interruption of disease transmission and prevention of future occurrences. Epidemiological investigations identify contamination sources and assess preventive measures (125). Implementing HACCP practices enhances food safety across production chains, thereby significantly benefiting public health (126).

Use of bacteriophages

Bacteriophages (phages) infect bacteria and are classified as lytic or lysogenic (127, 128). They are promising alternatives to antibiotics, owing to their bacteriolytic activity, specificity, self-limiting nature, and ability of genetic manipulation (129, 130, 131). Synthetic biology and genetic engineering enhance phage antibacterial efficacy, safety, and adaptability, enabling targeted pathogen elimination while preserving beneficial microbiota (132, 133). Phage biocontrol is an eco-friendly method that enhances food safety and nutritional value (134). Experimental studies that applied bacteriophage preparations (in single or cocktail form) to experimentally infected poultry and poultry products through different modes of administration and outcomes of phage treatment are outlined in Table 3(135). However, phage applications are also challenging for food processors (136). Higher concentrations are required during application, which can potentially increase costs (136, 137, 138). Bacterial resistance to frequently used or narrow-range phages can be managed by using engineered natural phages (139).

Table 3.

Overview of experimental studies examining the use of bacteriophages to reduce Salmonella spp. in poultry and related products

| Experimental model | Phage | Inoculation dose* | Phage delivery method | Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Broiler chicken |

Three Salmonella phages | 109–11 PFU | Oral | Within 24 h, the bacteriophage decreased cecal colonization of S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium by at least 4.2 and 2.9 log CFU/ml, respectively. | (198) |

|

Leghorn chicken

specific-patho gen-free (SPF) |

Three-phage cocktail | 1010 PFU | Oral | The bacteriophage cocktail reduced Salmonella levels in the chicken cecum when administered either one day prior to or immediately following bacterial infection, and on the subsequent days post-infection (dpi). | (199) |

|

Broiler chicken |

Three-phage cocktail | 1011 PFU | Oral | In the group treated with bacteriophages, the number of S. Enteritidis PT4 colony-forming units per gram of cecal content decreased by 3.5-fold. | (200) |

|

Chicken carcasses | Salmonella spp. phage | 109 PFU/ml | Spraying | In two experiments, S. Enteritidis was not found, while the remaining two trials demonstrated a reduction of at least 70%. | (201) |

| SPF chicks | Salmonella spp. phage |

1.18

× 1011–1.03 × 102 PFU | Oral | Analysis of the cecal contents revealed a modest reduction in Salmonella levels at 3 dpi, followed by a more significant decrease at 5 dpi. From 7 dpi onwards, until the study concluded at 15 dpi, all chicks tested negative for Salmonella. | (202) |

| Broiler chicks |

Mixture of bacteriophage |

2.5 × 109–7.5 × 109 PFU | Oral | Treatment resulted in a decrease of S. Enteritidis in cecal contents at 12 and 24 h post-administration when compared to the untreated control groups. | (203) |

|

One-day-old chicks |

Bacteriophage ΦCJ07 |

105, 107 and 109 PFU | Oral | All treatments effectively reduced Salmonella colonization in the intestines of both the challenged and contact chickens. Following three weeks of treatment, 70% of contact hens administered with bacteriophage at a concentration of 109 PFU/g showed no detectable intestinal Salmonella. | (204) |

|

Seven-day old chickens |

Three different Salmonella-specific bacteriophages | 103 PFU | Spray | The application of competitive exclusion combined with bacteriophage resulted in a reduction of the average S. Enteritidis cecal count to 1.6 × 102 CFU/g, which was lower than 1.56 × 105 CFU/g observed in the control group. | (205) |

|

Six-week-old chickens | S. Gallinarum (SG)-specific bacteriophage | 106 PFU | Oral | Contact hens administered with the bacteriophage exhibited significantly lower mortality rates than their untreated counterparts. | (206) |

| Broiler chicks | S. Enteritidis phage | 108 PFU | Oral | On the 14th day of the trial, the application of bacteriophage treatments substantially decreased the occurrence of S. Enteritidis in cloacal swab samples. | (207) |

| Broiler chicks |

P22hc-2, cPII and cI-7 and Felix 0 | 5 × 1011 PFU | Oral | Hens treated with bacteriophages exhibited bacterial populations in their ceca that were 0.3–1.3-fold lower when compared to the untreated control group. | (208) |

|

Ten-day old chickens |

Three lytic phages | 103 PFU |

Spray and Oral | The use of bacteriophages in aerosol spray form led to a 72.7% reduction in the occurrence of S. Enteritidis infection. Furthermore, measurements of S. Enteritidis levels showed that administering phages through both coarse spray and drinking water methods reduced bacterial colonization in the intestinal tract. | (209) |

|

White Leghorn chicks | Φ st1 | 1012 PFU/ml | Intracloacal inoculation | At 6 h post-challenge, the Salmonella count decreased to 2.9 log CFU/ml, and S. Typhimurium could not be detected at or beyond the 24 h mark. | (210) |

| Eggs | PSE5 | 4 × 107 PFU | Immersion | Following phage treatment, the concentration of Salmonella reduced to 2 × 106 CFU/ml. | (211) |

| Liquid egg | Pu20 |

108 or 109 PFU/ml |

Direct inoculation | When exposed to 4 and 25°C for 24 h, the number of viable bacteria in the experimental group decreased by as much as 1.06 and 1.12 log CFU/ml, respectively. The maximum antibacterial effectiveness reached 91.30 and 92.40% at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1000. | (212) |

|

Liquid whole egg |

Two phages (OSY-STA and OSY-SHC) | n/a |

Direct inoculation | A decrease of 1.8 and more than 2.5 log CFU/ml was observed for S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis, respectively. | (213) |

|

Chicken breasts and fresh eggs | UAB_Phi 20, UAB_Phi78, and UAB_Phi87 |

109 PFU/ml

and 1 × 1010 PFU |

Soaking in suspension and spraying | Chicken breasts exhibited decreased Salmonella levels exceeding 1 log CFU/g. A decline of 0.9 log CFU/cm2 in Salmonella was detected on the surface of fresh eggs. | (214) |

|

Raw chicken breast |

Five Salmonella phages | 3 × 108 PFU |

Suspension added on surface | When incubated at 25°C, the phage-treated group exhibited the most significant decrease in S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium counts, with reductions of 3.06 and 2.21 log CFU/piece, respectively. | (215) |

| Chicken breast |

Two-phage cocktails | 4 × 109 PFU/ml |

Added on surface | The concentration of S. Enteritidis in chicken breast decreased by 2.5 log CFU/sample over a 5 h period. | (216) |

| Chicken breasts |

SPHG1 and SPHG3 | 8.3 log PFU | Spotted | The bacteriophage cocktail was administered to chicken breast samples at MOI levels of 1000 or 100, resulting in a substantial decrease in the number of viable S. Typhimurium cells. | (217) |

|

Chicken breast meat |

Four Salmonella phage |

108, 109, and 1010 PFU/ml |

Directly added | Significant reductions in viable bacterial cell counts were observed when uncooked chicken breast specimens were exposed to a cocktail of all four bacteriophages at 4°C over a 7-day period. | (218) |

|

Chicken breast fillets | Salmonella lytic bacteriophage preparation | 109 PFU/ml | Spraying | The application of chlorine and PAA, followed by a phage spray, resulted in a decrease of Salmonella by 1.6–1.7 and 2.2–2.5 log CFU/cm2, respectively. | (219) |

| Chicken skin |

Eϕ151, Tϕ7 phage suspension | 109 PFU | Spray | Following phage treatment, the reduction in Salmonella levels was observed to be 1.38 log MPN for S. Enteritidis and 1.83 log MPN for S. Typhimurium per skin area. | (220) |

| Chicken skin | vB_StyS-LmqsSP1 |

2.5 × 108 PFU/cm2 |

Direct addition | The application of phage to chicken skin led to a decrease of approximately 2 log units in Salmonella count. This reduction was observed from the initial 3 h and persisted throughout the week-long study conducted at 4℃. | (221) |

|

Raw chicken meat and chicken skin |

SE-P3, P16, P37, and P47 | 109 PFU |

Direct inoculation | When stored at 4 and 25°C, bacteriophages effectively eliminated detectable levels of Salmonella in samples that initially contained 103 CFU/g. | (222) |

| Chicken meat | Five bacteriophages | 109 PFU/ml |

Direct inoculation | The application of a phage cocktail led to a 1.4 log unit decrease at 48 h when compared to the control at 10℃. | (223) |

| Chicken meat |

Three lytic bacteriophages Ic_pst11, Is_pst22, and Is_pst24 |

108, 107, and 106 PFU/ml |

Direct addition | When phage was applied at MOIs of 100, 1000, and 10,000, the number of viable S. Typhimurium cells significantly reduced after 7 h. The observed decreases were 1.17, 1.26, and 1.31 log CFU/g, respectively. | (224) |

| Chicken meat | STGO-35-1 | 4 × 106 PFU/ml |

Direct addition | The application of bacteriophage therapy resulted in a substantial decrease in S. Enteritidis, with a 2.5 log reduction observed. | (225) |

| Chicken frankfurters | Felix O1 | 5.25 × 106 PFU |

Direct addition of liquid | Two bacteriophage variants demonstrated the ability reduced S. Typhimurium levels by 1.8 and 2.1 log units, respectively. | (226) |

| Duck meat | fmb-p1 | 9.9 × 109 PFU |

Direct inoculation | A decrease of 4.52 log CFU/cm2 in S. Typhimurium levels was observed in ready-to-eat duck meat. | (227) |

Vaccination

Vaccines induce immunity without causing diseases, effectively reducing global infection rates (140, 141, 142, 143). Their efficacy varies based on formulation, with several vaccines currently in use and under development (Table 4) (93). Ty21a and Vi capsular polysaccharide vaccines effectively prevent typhoid and paratyphoid fevers (144), with Ty21a providing cross-reactive immunity to S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi (145, 146, 147) and Vi capsular polysaccharide vaccines inducing IgG production (148). Vi-conjugate vaccines are highly effective in children (149, 150, 151). However, the differences between typhoidal and non-typhoidal Salmonella strains restrict the application of typhoid vaccine technology to non-typhoidal variants (148). Vaccine development encounters challenges, including serovar genetic diversity, risks of vaccine failure, virulence reversion, tolerance to toxoid vaccines, and low immunogenicity of OMV vaccines (152, 153, 154). Continued research is essential for developing effective vaccines against evolving pathogens and diseases.

Table 4.

Available vaccines against Salmonella spp. in humans and animals

| Vaccines | Targets | Indications | Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Vi Conjugate (Vi-rEPA) | S. Typhi | Human | The effectiveness reaches up to 90% in children aged 2–5 years. There was a rapid generation of Vi-specific IgM and IgG, accompanied by a two-log decrease in bacterial shedding. | (150) |

|

Modified live S. Dublin vaccine (EnterVene-d) | S. Dublin | Cattle | Vaccinated cows exhibited enhanced cell-mediated immunity, with a 49% increase in antibody titers. The offspring of these vaccinated cows showed a more substantial increase in antibody titers, reaching 88.56%, indicating effective vertical transmission. | (228) |

| Ty21a | S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi B | Human | The T cell response exhibited cross-reactivity and multifunctionality, accompanied by an elevation in IgA production. Compared with the control, there was a 56% increase in IgA production against S. Typhi and a 38% increase against S. Paratyphi B. | (144, 147) |

|

M01ZH09, Single dose

independently attenuating deletion (S. Typhi (Ty2ΔaroCΔssaV) ZH9) | S. Typhi | Human | Swift and substantial production of IgG and IgA antibodies accompanied by bacterial elimination in feces within 7 days following infection, without any significant symptoms. | (229) |

|

GMMA, Generalized Modules for Membrane Antigens | S. Typhimurium, S. Typhi, and S. Paratyphi A | Human | Enhanced activation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells led to elevated IL-6 production. This triggered a robust production of bactericidal anti-LPS O-antigen antibodies and IgG, resulting in the total elimination of the bacteria. | (230, 231) |

| Vi Conjugate (Vi-CRM197) | S. Typhi | Human | Exhibited 89% effectiveness in preventing typhoid fever, with protection lasting for at least four years, and substantially elevated IgG antibody levels. | (151) |

| S. Typhi Vi polysaccharide tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine (Tybar) | S. Typhi | Human | Strong anti-Vi IgG responses were observed across all age groups, demonstrating significant protection for individuals of all ages, including children under two years old. The treatment showed an effecacy of 85% without any adverse reactions. | (149) |

|

AviPro Megan Vac 1 + A12:E13 |

S. Typhimurium, S. Enteritidis, and S. Heidelberg | Poultry | S. Enteritidis was fully eliminated within 10 days following infection, with only 6% of cases remaining positive after a second inoculation. Antibodies were not vertically transmitted. | (232) |

|

Chitosan-adjuvanted Salmonella subunit nanoparticle vaccine (OMPs-F-CS NPs) | S. Enteritidis | Poultry | Oral administration led to an increase in TLRs and Th1 and Th2 cytokine mRNA expression, along with elevated levels of OMPs-specific IgY and IgA antibodies in both saliva and intestine. The treatment resulted in a 7-fold decrease in Salmonella shedding when compared to that in the control group. | (233) |

|

Inactivated trivalent Salmonella enterica vaccine (Nobilis® Salenvac T; Intervet International B.V., Boxmeer, The Netherlands) |

S. Typhimurium, S. Enteritidis, and S. Infantis | Poultry | Booster dose administration in chickens resulted in a 3.9 log rise in the average antibody titer. This was accompanied by a 2.6 log decrease in cecal excretion of S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis, and a subsequent 1.3 log decline in S. Infantis shedding. | (234) |

|

Poulvac® ST (Zoetis Inc. New Jersey, USA) |

S. Typhimurium, S. Kentucky, S. Enteritidis, S. Heidelberg, and S. Hadar | Poultry | The liver and spleen exhibited a decrease of up to 50% in five Salmonella strains: S. Kentucky, S. Enteritidis, S. Heidelberg, S. Typhimurium, and S. Hadar. This reduction demonstrated cross-protective effects among the five bacterial variants. | (235) |

|

Autologous killed trivalent vaccine (Tri-Vaccine) |

S. Typhimurium, S. Enteritidis, and S. Heidelberg | Poultry | Eight days after infection, 58% of the cloacal swabs collected from infected birds showed complete elimination of the bacteria. | (232) |

Pro- and prebiotics

Probiotics, including lactobacilli, bifidobacteria, and other lactic acid bacteria (LAB), may prevent Salmonella colonization in the gut by competing with pathogens, stimulating immune responses, and increasing gastrointestinal pH (155, 156, 157). Specifically, Lactobacillus acidophilus inhibits Salmonella spp. by secreting lactic acid, thereby lowering the intestinal pH (158). Prebiotics are fermented food ingredients that enhance the growth or activity of beneficial bacteria in the host colon and provide health benefits through their nutraceutical and nutritional value, promotion of beneficial microbiota, resistance to digestion, and intestinal fermentation (159, 160). Prebiotics support beneficial bacteria that form biofilms on the gut epithelial cells and inhibit pathogenic adhesion (161). Thus, the consumption of prebiotic-rich foods is an effective intervention against pathogenic gut bacteria (162).

Antimicrobial peptides

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are a diverse group of small peptides that are crucial to the innate immune system and function through various membrane-targeting and non-membrane-targeting mechanisms (163, 164, 165). Their broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties make them promising alternatives to antibiotics with a low likelihood of developing AMR strains (166). Numerous AMPs, such as 1018-K6, A11, BmKn-2, P7, Microcin J25, HJH-3, A3-APO, IK12, Css54, Ctx(Ile21)-Ha, AvBD7, hBD-1, hBD-2, and gallinacins, show efficacy against Salmonella and other foodborne pathogens, influencing immune regulation, growth performance, and intestinal microbiota (166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179). However, challenges, such as bacterial resistance and potential host cell toxicity, necessitate further research to enhance bioavailability and develop cost-effective production methods for their full utilization as antibiotic alternatives.

Nanoparticles

Nanoparticles (NPs) target pathogen entry sites and bypass gastrointestinal barriers, and their efficacy is determined based on size (1–500 nm) (180, 181, 182). Polymeric NPs (50–500 nm) effectively cross the intestinal mucosal barrier and are absorbed by antigen-processing cells, thus making them ideal for oral use (183). Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) possess size- and shape-dependent photothermal properties, enhancing delivery potential due to easy functionalization (173, 184, 185, 186, 187, 188, 189, 190, 191). Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) effectively combat gram-negative bacteria (192, 193). Chitosan nanoparticles (CNP), tested as oral Salmonella vaccine carriers, elicit immune responses in broilers and demonstrate acid stability (182, 194). Polymeric NPs resist stomach pH variations, slowly release antigens, are degradable, aid antigen-presenting cell uptake, and act as adjuvants, thereby making them an effective drug delivery system (194). Combining NPs with antibacterial agents prevents Salmonella from spreading in food and enhances human safety. Oral NP delivery with antibiotics has revolutionized typhoid fever treatment by reducing pathogen resistance, cytotoxicity, and adverse effects, while improving antibiotic localization and modulating drug-pathogen interactions (195, 196, 197).

CONCLUSIONS

Salmonella is a major foodborne pathogen and is the leading cause of gastroenteritis in humans and animals. Salmonella-contaminated food and water pose significant risks to global health. Severe complications and higher mortality rates are common in infants, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals, with an estimated annual economic burden of $4–11 billion annually in the U.S. S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium are prevalent in both humans and poultry, necessitating the prevention of contamination of animals, vegetables, and fruits.

The prevention of non-typhoidal Salmonella infection is challenging, owing to the number of serovars and regional prevalence influenced by various factors. Although S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium are globally widespread, other serovars prevail in specific regions. Treatment differs for non-typhoidal and typhoidal Salmonella, with frequent antibiotic use for non-typhoidal infections, potentially leading to relapse and prolonged carrier states. Treating MDR strains is complicated, and no single vaccine is effective against all forms. The evolution of drug resistance has necessitated the study of serovar-specific resistance genes, with recent resistance to various antibiotics in multiple serovars.

Improved interventions by professionals, academia, and the food-processing industry are needed to address these “biological bombs.” The strategies discussed in this review can reduce Salmonella contamination. Stringent local and international policies are required to regulate the trade of live animals, plants, and animal products. Periodic epidemiological studies should trace the prevalent serovars, identify distribution vehicles, and recommend control measures to prevent or halt the trade of contaminated food or live animals in affected countries.

Each approach has unique advantages and limitations, necessitating careful consideration and further research to determine its effectiveness, safety, and scalability. As traditional treatments such as antibiotics are less effective, adopting modern and improved strategies is essential. These strategies should involve the combined use of alternative antibiotics, enhanced biosecurity measures, and prudent use of antibiotics. A comprehensive approach is the key to controlling the spread of Salmonella. Additionally, a One Health approach and ongoing collaboration among researchers, healthcare professionals, veterinarians, and policymakers in antibiotic stewardship are vital for protecting public health and food safety from prevalent foodborne pathogens such as Salmonella.