INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus, a significant opportunistic pathogen, is responsible for a wide variety of clinical diseases (1, 2). Since the 1960s, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) has spread globally, creating an urgent need for strategies to effectively control resulting infections. In the post-antibiotic era, anti-virulence drugs, which target virulence factors and disarm microorganisms without killing them or inhibiting their growth, have been considered primary measures (3). Virulence factors are bacterial products that promote disease by facilitating colonization, adhesion, invasion, toxigenesis, and immune evasion. Antivirulent agents offer advantages over traditional antibiotics, such as reduced selection pressure and minimal disruption of the commensal microbiota (4, 5).

S. aureus harbors a remarkable array of virulence factors, including cytolytic toxins, coagulases, multilayered biofilms, and immune-evading systems (6), whose expression is tightly regulated by interactive networks known as two-component systems (TCSs), which are responsive to specific environmental cues (7). To date, S. aureus is known to encode 16 TCSs, most of which independently sense and respond to their respective signals. The SaeRS system, one of the staphylococcal TCSs, controls the production of over 20 virulence factors, including hemolysins, leukocidins, superantigens, and surface proteins (8). Encoded within a four-gene operon (saePQRS), SaeS is a sensor histidine kinase critical for the signal transfer process. The Sae system consists of two transmembrane segments that span across the cell membrane and are located externally, where specific amino acids (M31, W32, F33) interact with human neutrophil peptides (HNPs), unsaturated fatty acids, lipoteichoic acid, and metal ions such as copper, zinc, and iron, leading to the induction of virulence factors (9, 10, 11, 12). As severalbacterial factors are the products of the Sae regulon, strategies that effectively inhibit the SaeRS TCS may serve as potent anti-virulence therapeutic approaches against S. aureus infections.

Recent studies have employed in silico methods for discovering new antibiotics. With the current advancements in molecular docking simulations and machine learning, antibiotic development has shifted toward predicting molecular properties to identify novel classes of antibiotics (13). This in silico method of drug discovery based on molecular docking offers several advantages, such as the exploration of vast chemical spaces beyond the reach of traditional experimental approaches (13). In addition, computational methods for predicting the binding interaction between a ligand and a receptor protein can significantly shorten the time and reduce the cost of drug development (14).

Using this in silico approach, several antibiotics encompassing a wide range of molecular groups have been discovered, such as rhodomyrtone, guinuclidine, and berberine (15). Notably, among the identified groups are nutraceuticals, compounds derived from natural sources that provide significant medical or health benefits, including anti-cholesterol, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial effects (16). Among the bioactive compounds found in nutraceuticals are essential minerals, polyphenols, and vitamins. Nicotinamide, also known as vitamin B3, is an antibacterial compound that enhances neutrophil-mediated killing of S. aureus(17). Menadione, or vitamin K3, exhibits antibacterial and antibiofilm activities against MRSA (18). Previous studies have shown that riboflavin (vitamin B2) effectively inhibits the growth of S. aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Salmonella Typhi, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa(19). Furthermore, the combination of azithromycin with riboflavin reduces the severity of S. aureus infection in septic arthritis (20). Moreover, these nutraceuticals are cost-effective and relatively safe, with minimal side effects compared with pharmaceutical drugs, although their mechanisms of action have not been fully elucidated yet.

In the present study, to screen for potent inhibitors of S. aureus virulence factors, we investigated the molecular binding scores of nutraceuticals, using staphylococcal SaeS protein as a target. Among the 111 molecules examined, vitamins and their derivatives had higher predicted binding scores. Experimental analysis suggested that riboflavin can be a potential inhibitor of bacterial growth and staphyloxanthin production, a major virulence factor regulated by the SaeRS system. Our results suggested that 1) in silico molecular docking prediction is a powerful tool for discovering novel drug candidates and 2) riboflavin holds promise as a novel antivirulent agent against S. aureus infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The bacterial strains and vitamins used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. aureus strains were grown overnight at 37℃ in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth (Oxoid-CM1135, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). When cells were cultured on RPMI1640 medium (#SH30027.01, Hyclone, UT, USA), the BHI-grown strains were washed twice with RPMI1640 medium, diluted to an initial OD600 of 0.05, and grown in fresh RPMI1640.

Table 1.

List of the strains and plasmids used in this study

For the vitamin treatments, vitamins were prepared as 10 mg/ml stock solutions and supplemented in RPMI1640 medium. Thiamin (vitamin B1), niacin (vitamin B3), pantothenic acid (vitamin B5), pyridoxine (vitamin B6), and cobalamin (vitamin B12) were dissolved in distilled water (DW). Riboflavin (vitamin B2) and folate (vitamin B9) were dissolved in 0.1 N NaOH as they are soluble in basic solutions but not in water.

Generation of the saeS-deletion strain

The deletion of saeS in S. aureus Newman was performed using the engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system described in Chen et. al (21). The pCasSA-∆saeS plasmid was constructed using pCasSA obtained from Addgene (#98211, Watertown, MA, USA) as the backbone. The constructed pCasSA-∆saeS plasmid was electroporated into S. aureus RN4220, and the final extracted plasmid was then transformed into S. aureus Newman. Genome editing was verified via PCR and sequencing using genomic DNA.

Binding prediction and virtual screening

The Local ColabFold Batch based on AlphaFold2 was used to predict the binding of the SaeS, SaeR, and HNP-1 proteins. The amino acid sequences of histidine protein kinase SaeS (SaeS, UniProt ID: Q99VR8) and response regulator SaeR (SaeR, UniProt ID: Q840P8) were obtained from the Uniprot Knowledgebase (UniProtKB, https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/), and the sequence of human alpha-defensin 1 (HNP-1, PDB ID: 4DU0) was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org/). The model applied was alphafold2_multimer_v3 and, to improve the prediction accuracy, the Amber and Template options were activated. The recycle and ensemble numbers were set to 10 and 3, respectively. Binding residues were calculated using the ChimeraX program (https://www.rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimerax/) by calculating the H-bonds. Distance and angle tolerance for the analysis were set to 1 Å and 20°, respectively, to ensure the effective identification of hydrogen bonds involved in the binding interactions. The UCSF Chimera-based AutoDock Vina software (http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/docs/ContributedSoftware/vina/vina.html) was used predict the binding of the SaeS–SaeR complex with 111 nutraceutical compounds. The chemical structures of the small molecules constituting this group were derived from DrugBank, and the potential scores for their binding to the SaeS receptor were predicted. The scores were visualized in ChemBiz2 (installed via Cytoscape App Manager, https://apps.cytoscape.org/). The lower and higher scores were represented by red and blue ovals, respectively. For further in silico analysis of flavone, anthraquinone, and rhodomyrtone, PubChem CID parameters (PubChem, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) were used to build structures in UCSF Chimera, and binding predictions were made. The chemical structures of the compounds were drawn using MolVieW (https://app.molview.com/)

Growth analysis

The S. aureus strains were initially cultured overnight in BHI broth at 37°C. The bacterial cells were washed twice with RPMI1640 medium, diluted to an initial OD600 of 0.05, and cultured in fresh RPMI1640. After incubation, OD600 measurements were taken at 0, 4, 8, and 24 h using a spectrophotometer to assess bacterial growth. Each time point represents the mean OD600 of at least three independent biological replicates.

Staphyloxanthin production assay

S. aureus was grown overnight in BHI, washed twice with RPMI1640, subjected to 1:100 dilutions in 5 ml of fresh RPMI1640, and incubated overnight at 37℃ in 14 ml round tubes with shaking. After incubation, cells were collected by centrifugation at 12,300 g for 1 min (five times with 1 ml each) and washed with 0.9% (w/v) NaCl twice. Staphyloxanthin was extracted using 200 µl of ice-cold ethanol at room temperature. After 30 min, the cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 min, and 150 μl of the supernatant was transferred from each tube into wells of a 96-well plate. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm on a microplate reader (Epoch™ Microplate Spectrophotometer, BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA).

RESULTS

Virtual screening of nutraceuticals as potent inhibitors of SaeS in S. aureus

In the SaeRS TCS, SaeS is a sensor histidine kinase that undergoes autophosphorylation in response to cognate environmental signals (9). Subsequently, the phosphoryl group is transferred to SaeR, activating the transcription of its target genes (8). Currently, only a few SaeS activation signals have been identified, including HNPs, calprotectin, and beta-lactam antibiotics (8, 10, 14). Particularly, HNPs (also known as α-defensins) , which are antimicrobial peptides produced by human neutrophils, are major activation signals (9). However, the binding mechanism and structural interaction between them and SaeS remain unclear.

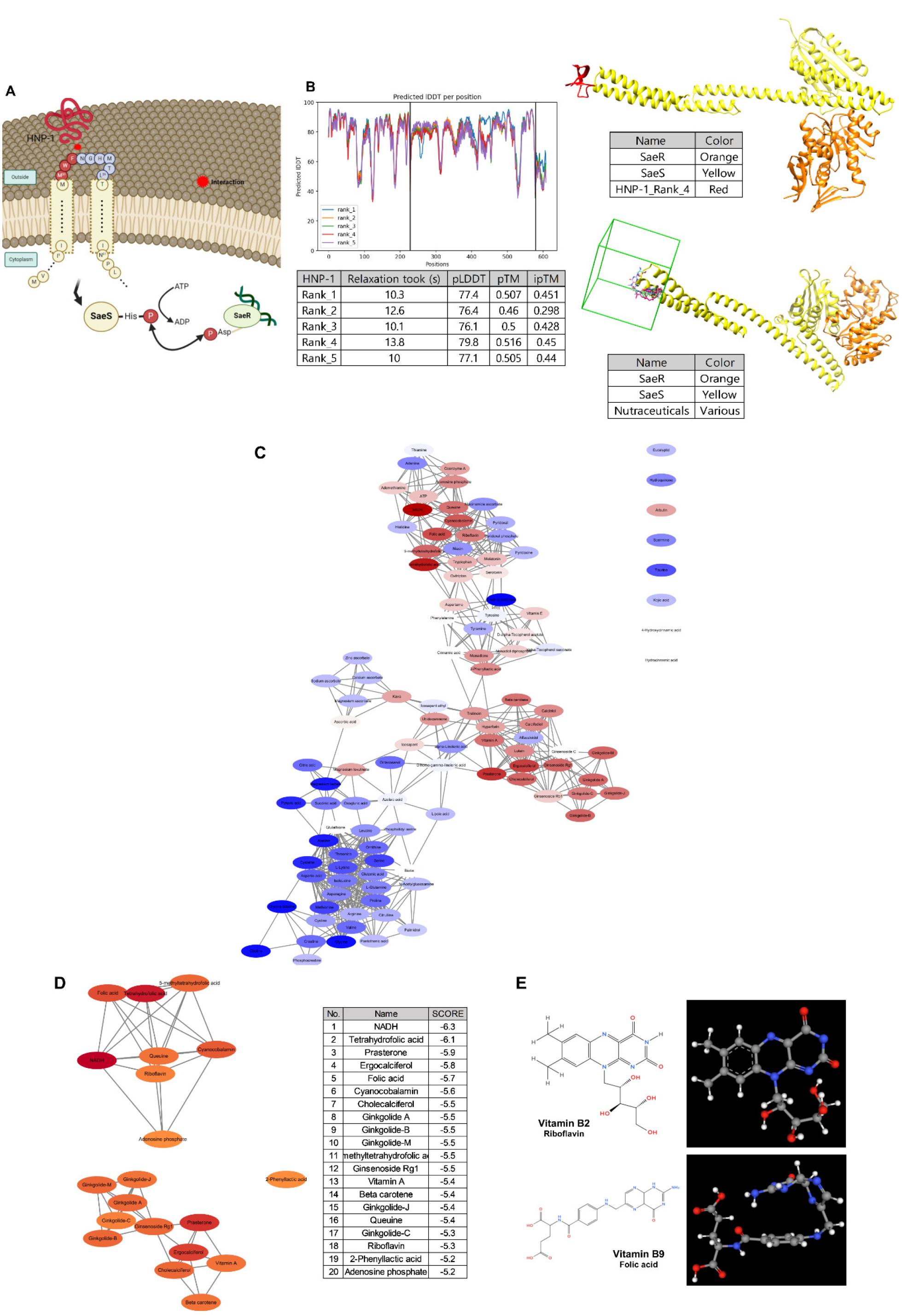

To screen for effective functional small molecules that inhibit the SaeRS system, we first predicted the binding of HNP-1 to SaeS and identified the probable binding region for the small molecules. As SaeS is classified as an intramembrane-sensing histidine kinase (8, 22), the extracytoplasmic region was selected as the predicted binding region. As shown in Fig. 1A, the SaeS binding site of S. aureus consists of a short extracellular loop connected by two transmembrane segments that span across the cell membrane. Externally located specific amino acids (M31, W32, and F33) play a role in signal recognition and transduction (12). HNP-1 binds to the extracellular loop of SaeS, activating the SaeS protein.

Fig. 1

Prediction of the binding of SaeS with HNP-1. (A) A schematic diagram of the staphylococcal SaeS structure and interactions with SaeR and HNP-1. (B) Predicted structure of SaeS binding to SaeRS and HNP-1 using ColabFold Batch based on AlphaFold2. In the table, “Relaxation” indicates the time (s) for the structural relaxation of the protein model, “pLDDT” indicates the confidence of the predicted model structure, “pTM” is the accuracy of the folding of the protein model (values closer to ≤ 0.5 indicating higher confidence), and “ipTM” is the confidence of the predicted binding site between proteins (values closer to ≤ 0.5 indicating higher confidence). The in silico binding prediction for representative nutraceuticals in the HNP-1 binding site using AutoDock Vina was performed based on the predicted model structure. The green box indicates a search space located on the extracellular loop of SaeS as a putative ligand-binding pocket. (C) Visualization of the binding affinities for 111 nutraceuticals using Cytoscape. Lower (higher binding affinities) and higher (lower binding affinities) scores are shown as red and blue ellipses, respectively. (D) Visualization of the top 20 nutraceutical compounds using Cytoscape, with lower (higher binding affinities) and higher scores (lower binding affinities) represented as red and orange ellipses, respectively. The list of the top 20 nutraceuticals and their binding scores is provided. (E) Chemical structures of vitamin B2 and B9.

We used ColabFold-AlphaFold2 to predict the docking site of HNP-1 on the extracellular loop of SaeS within the SaeRS structure and ranked the models based on the scores of the predicted local distance difference test (pLDDT), which measures the prediction confidence of side-chain angles and per-residue accuracy in the local structure. Higher scores indicate a higher confidence and more accurate prediction, with pLDDT values above 70 being generally considered to correspond to a correct backbone. The top five models showed similar pLDDT scores of 79.8, 77.4, 77.1, 76.1, and 76.4, and one of the model is shown in Fig. 1B. Based on the binding model, we performed an insilico molecular docking using AutoDock Vina integrated with UCSF Chimera to predict the interactions of functional small molecules classified as nutraceuticals in DrugBank with SaeS as the receptor. Each molecular docking prediction was scored (binding score, kcal/mol) to estimate the binding free energy, based on the conformational preferences of the receptor–ligand complexes and experimental affinity measurements (23). The binding scores were visualized in Cytoscape, in Fig. 1C. Among the 111 molecules examined, the top 20 molecules with high predicted binding scores (Fig. 1D) were classified as vitamins and their derivatives, such as riboflavin and folate (Fig. 1E). Overall, functional small molecules, including riboflavin and folate, were predicted to be potent molecules that interact with the docked residues in SaeS.

Evaluation of vitamins as potent inhibitors of staphyloxanthin production in S. aureus

Considering water-soluble vitamins are potent inhibitors of SaeS, we analyzed the effects of vitamin supplementation on bacterial growth and staphyloxanthin production. Recently, we have revealed that the staphylococcal SaeRS function is closely associated with staphyloxanthin production, particularly in the strain Newman (manuscript submitted). Staphyloxanthin, a yellow-to-orange pigment of S. aureus, is a carotenoid with numerous conjugated double bonds that can neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS), exerting antioxidative effects and contributing to neutrophil resistance (24).

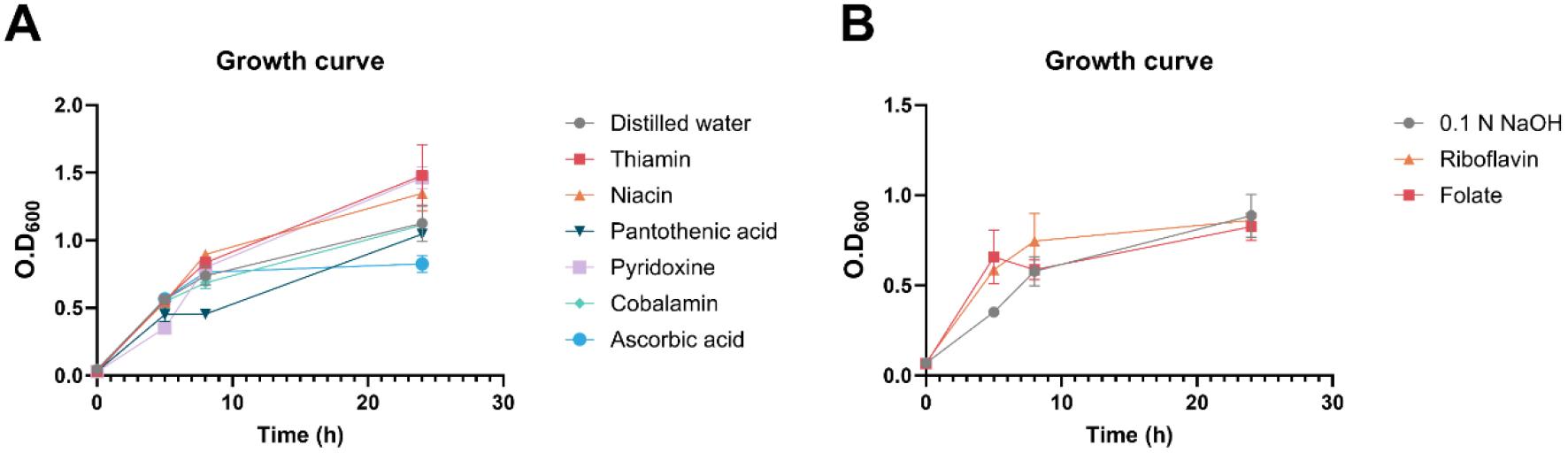

Most water-soluble vitamins, including thiamin, niacin, pantothenic acid, pyridoxine, and cobalamin, were shown to have no effects on bacterial growth, except for vitamin C, also known as ascorbic acid (Fig. 2A). The same was observed for riboflavin and folate. Considering that these two molecules are only stable at basic pH conditions, 10% of 0.1 N sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution was added as a vehicle control (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2

Effects of vitamins on bacterial growth in S. aureus. (A-B) Bacterial growth with water-soluble vitamin supplementation using distilled water (DW) (A) and 0.1 N NaOH (B) as the vehicle control. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the data were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA.

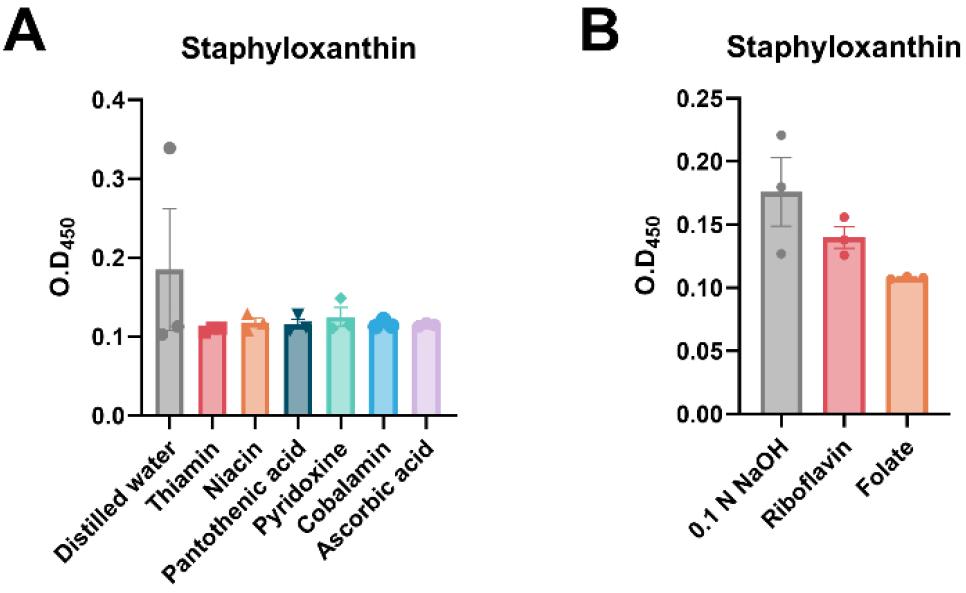

Vitamin C is a well-known free radical scavenger with antioxidant properties. Its antimicrobial activity against various bacterial strains, such as Bacillus subtilis, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Enterococcus faecalis, and Staphylococcus aureus, has been documented (25). Although the mechanism regulating the antimicrobial action of vitamin C is highly strain- and concentration-dependent, we believe that it exerts its effects via exposing bacterial cells to oxidative stress. Vitamin C generates ROS, which participate in the Fenton reaction in the presence of free iron (Fe²⁺). This reaction produces highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (OH-) that cause oxidative damage to bacterial membranes, proteins, and DNA, resulting in cell death (26, 27). With regard to staphyloxanthin production, no significant differences were observed in effects of vitamin supplements at 1 mg/ml and their respective vehicle controls (Fig. 3). However, among the tested vitamins, riboflavin and folate showed a more pronounced effect compared with the controls, which warrants further investigation into their potential effects on S. aureus.

Fig. 3

Effects of vitamins on bacterial virulence expression in S. aureus. (A-B) Staphyloxanthin production with water- soluble vitamin supplementation using distilled water (DW) (A) and 0.1 N NaOH (B) as the vehicle control. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the data were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA.

Effect of riboflavin on the inhibition of staphyloxanthin production in S. aureus

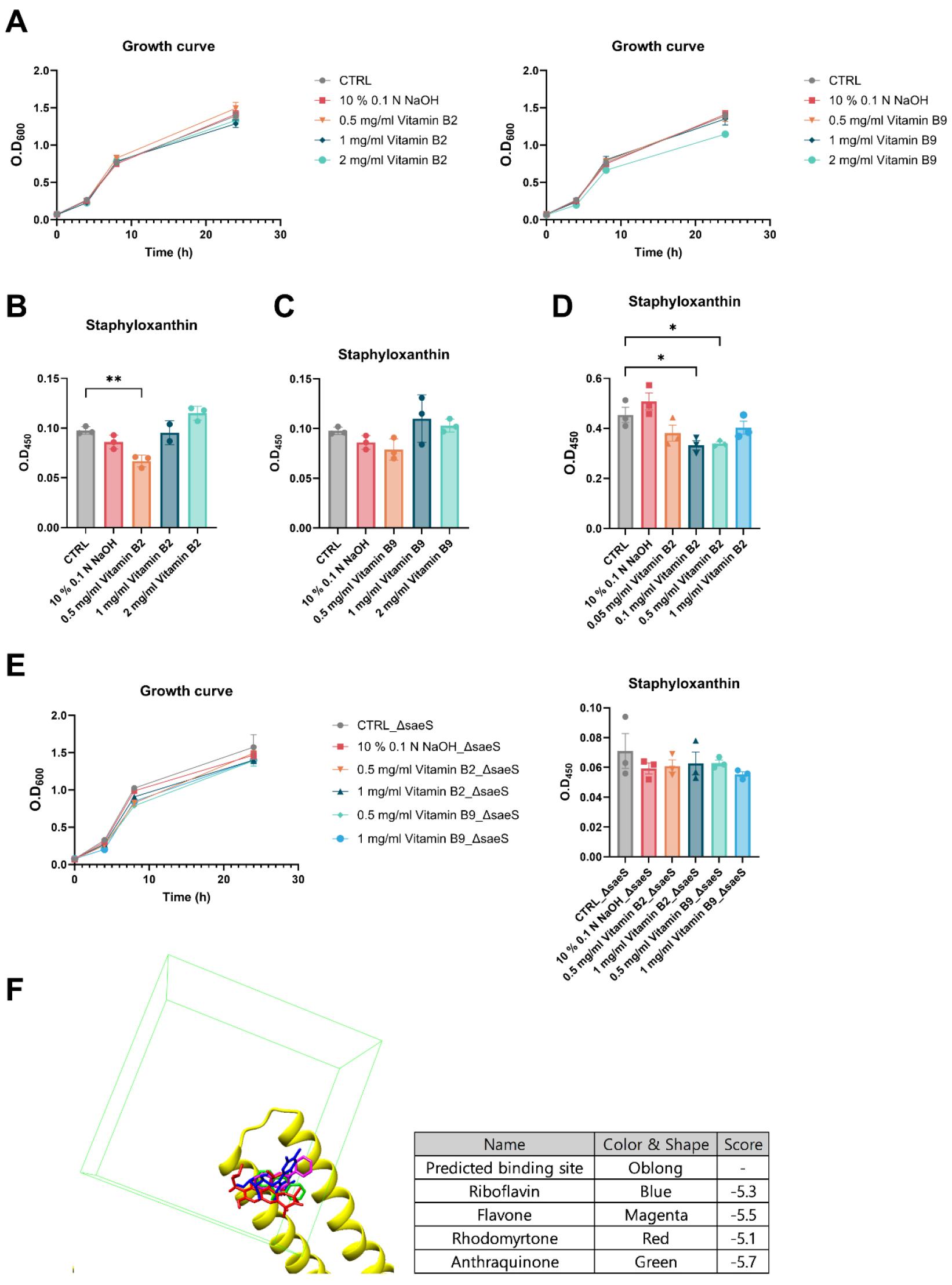

Riboflavin and folate are essential micronutrients involved in multiple oxidative-reduction processes and metabolic pathways. Riboflavin has garnered attention due to its potential antimicrobial action as a photosensitizer via the induction of oxidative damage in bacterial cells (28). Folate is a key mediator in bacterial nucleotide synthesis, and anti-folate drugs have been developed as potent antimicrobial compounds (29). Here, we analyzed the dose-dependent effects of riboflavin and folate on bacterial growth and staphyloxanthin production at concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 2 mg/ml (Fig. 4A-C). Both riboflavin and folate had no effect on bacterial growth. Riboflavin significantly inhibited staphyloxanthin production in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). In contrast, folate exhibited no inhibitory effect on staphyloxanthin production (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4

Effects of vitamin B2 and B9 on bacterial growth and virulence expression in S. aureus. (A) Bacterial growth with vitamin B2 and B9 supplementation. (B-C) Staphyloxanthin production with vitamin B2 (B) and B9 (C) supplementation at concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 2 mg/ml. (D) Staphyloxanthin production with vitamin B2 supplementation at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 0.5 mg/ml in BHI medium. (E) Growth of and staphyloxanthin production in saeS-deletion strain (ΔsaeS) with vitamin B2 and B9 supplementation in the. (F) In silico binding prediction of potent inhibitors of staphyloxanthin production, including riboflavin (blue), flavone (magenta), rhodomyrtone (red), and anthraquinone (green). All experiments were conducted in triplicate. Significant differences among the groups are indicated by asterisks at the 95% (*) and 99% (**) significance levels based on the results of one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis.

Further, the effects of B2 at lower concentrations in BHI medium were re-evaluated to assess its activity under different conditions, and the most substantial inhibitory effect was observed at concentrations between 0.1 and 0.5 mg/ml (Fig. 4D). As riboflavin was identified as a potent SaeS inhibitor, its effect on the growth and staphyloxanthin production of a saeS-deletion strain was further tested (Fig. 4E). In this strain, riboflavin did not affect either growth or virulence, suggesting that its inhibitory effects depend on the presence of SaeS, indicative of its potential as an effective antimicrobial agent against SaeS-dependent bacterial pathogenesis. Although chemically distinct to riboflavin, flavone, anthraquinone, and rhodomyrtone, which are known to inhibit staphyloxanthin production, also showed comparable predicted binding scores for SaeS (Fig. 4F). Collectively, these results suggested that riboflavin may serve as a potent antivirulent agent against S. aureus infection by targeting the global transcriptional regulator of virulence factors, i.e., the SaeRS system.

DISCUSSION

Given the increasing resistance of S. aureus to a broad range of antibiotics and its high pathogenicity, effective measures are urgently needed to prevent resulting infections. In this study, we performed in silico molecular docking predictions of naturally occurring, functional small compounds targeting SaeS (a regulator of staphylococcal virulence expression) as the receptor protein. Soluble vitamins demonstrated higher binding probabilities, with riboflavin exhibiting a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on SaeS-associated staphyloxanthin production.

Riboflavin is an essential component of metabolic coenzymes such as flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), which hold key roles in a wide range of metabolic pathways related to energy metabolism, respiration, growth, and development (30). In addition, riboflavin has shown antimicrobial activity against various infectious diseases. The application of exogenous riboflavin in vivo has been shown to protect animal models against lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced shock via modulating immune responses, for example by reducing the production of proinflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide (31), increasing the level of heat shock protein 25 (32), and modulating the stimulation of macrophages (33).

Although the direct antibacterial effects of riboflavin on pathogenic bacteria remain unclear, its synergistic activity with antibiotics such as linezolid and azithromycin has been reported (20, 34). In addition, riboflavin acts as a natural photosensitizer, causing the photodynamic inactivation of pathogens in combination with ultraviolet light by inducing ROS accumulation and oxidative stress (35). These combination treatments have also been shown to inhibit biofilm formation and damage bacterial nucleic acids (36, 37). Our finding that riboflavin inhibits staphyloxanthin production in S. aureus suggests a potential role of this molecule as an antimicrobial agent to treat infectious diseases.

Several SaeS inhibitory molecules, such as the silkworm apolipophorin protein complexes with lipoteichoic acid, have been reported, although their specific mechanisms remain unclear (38). In this study, we predicted that riboflavin could bind to specific sites within the Sae system, suggesting a potential inhibition of the SaeS protein function via the disruption of its activation. In addition, riboflavin demonstrated actual inhibition of S. aureus virulence in an SaeS-dependent manner. Although other factors may influence the inhibitory effects of riboflavin on S. aureus metabolism and virulence expression in, we propose that it primarily binds to SaeS, interferes with its activation, and ultimately suppresses SaeRS-associated virulence expression in this bacterium.

Staphyloxanthin is a yellow-to-orange-colored carotenoid pigment produced by S. aureus. Clinical isolates of MRSA that produce staphyloxanthin tend to survive longer compared with those forming pale colonies, indicating that staphyloxanthin confers MRSA an advantage in immune evasion by neutralizing ROS (39). Staphyloxanthin is recognized as a crucial virulence factor in S. aureus and thus as a potential target for anti-virulence therapy (24). Several natural compounds, including anthraquinones (6-deoxy-8-O-methylrabelomycin and tetrangomycin) (40), rhodomyrtone (41), and phosphorosulfates (BPH-652, BPH-698, and BPH-700) (42), have shown inhibitory effects against staphyloxanthin biosynthesis. In addition, flavone and flavonoids have been reported to reduce the production of staphyloxanthin and alpha-hemolysin in S. aureus(43). Notably, flavone exhibited superior inhibitory effects on staphyloxanthin compared with other flavonoids, making S. aureus cells 100 times more susceptible to hydrogen peroxide.

Despite the similarity in names, flavins are chemically distinct from flavone and flavonoids. In fact, the chemical structure of riboflavin shares common features with that of other inhibitors, such as anthraquinone and rhodomyrtone, particularly the presence of a tricyclic structure consisting of three interconnected rings. Our predictions for binding of histidine kinase SaeS with riboflavin, flavone, anthraquinone, and rhodomyrtone yielded similar scores, suggesting that the common structural characteristics may contribute to comparable binding affinities. Although the specific mechanisms of action of riboflavin and other inhibitors targeting staphyloxanthin production have yet to be fully elucidated, the results suggest that further exploration of compounds with similar structural characteristics could lead to the discovery of novel potent inhibitors of S. aureus virulence factors.

Despite the significant findings reported, this study has potential limitations. First, while it demonstrated the inhibitory effect of riboflavin on the virulence of S. aureus in vitro, the compound’s efficacy as an antivirulent agent is yet to be examined in vivo. In addition to the concerns regarding efficacy, the involvement of riboflavin in various cellular metabolic processes necessitates a precise evaluation of its safety in animal and human hosts in vivo, despite it being widely considered safe and commonly used as a food supplement (44). Second, this study focused on the effects of riboflavin on staphyloxanthin production alone. Considering that SaeRS is a master transcriptional regulator of virulence factors, the effects of riboflavin on other SaeS-regulated virulence factors, such as alpha-hemolysin and coagulase, need further investigation. Third, for the application of riboflavin as a therapeutic agent to reduce the virulence of S. aureus, more sophisticated clinical evaluations assessing its effects against staphylococcal infections are required.

In the present study, based on in silico molecular docking predictions, we identified riboflavin as a potential antivirulent agent for S. aureus infections. Owing to its historical use and presence in natural products, riboflavin holds potential as a dietary supplement or as part of a combined therapeutic regimen that could also serve as a prophylactic measure against infectious diseases.